Bats have long been known as important hosts of zoonotic viral pathogens. Zoonotic viruses that bats transmit are capable of infecting humans and have caused devastating infections throughout the world. Common zoonotic viruses include the Ebola virus and the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses. Although retroviruses are known to have a major global impact on human health, the zoonotic potential of bat retroviruses is currently unknown.

Knowledge of bat retroviruses has been growing over the last two decades due to discovering retroviral sequences within the bat genome. These sequences are present due to the key features of the retroviral replication cycle that includes the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) and its integration into the host genome, giving rise to a provirus. These proviruses occasionally get fixed to the host species' gene pool, giving rise to endogenous retrovirus (ERV). The ERVs eventually accumulate mutations, become fragmented, defective, and incapable of producing viral proteins. Thus, these ERVs act as genomic fossils that help to provide the history of retroviral infections in animals and humans and currently circulating exogenous retroviruses (XRV).

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a new stimulus to identify the potential viral threats brought about in the future by bats. This study published in the ASM Journals reviews how bats were affected by retroviruses and the current exogenous retroviruses circulating in bats. It also helps to determine whether the retroviral sequences found in the host belong to the endogenous or exogenous viruses. Additionally, the ability of bats to receive and transmit retroviruses from other species is also examined, along with whether the exogenous viruses in bats will pose a threat to humans.

Retrospective study of bat retroviruses

The earliest association between bats and retroviruses was studied in cell lines from the lung tissue of the Brazilian free-tailed bat, which suggested that bat cells are susceptible to retroviral infection from diverse mammalian species.

Culture-independent methods such as high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies and PCR were used to discover these retroviruses. The first report of retroviral sequence in bats was published in 2004 that described the presence of an ERV from genus Betaretrovirus within the genome of rodents. In 2008 a defective ERV was identified from genus Gammaretrovirus in little brown bats.

The adoption of HTS technology has led to the discovery of various betaretroviruses and gammaretroviruses across different bat species. In 2020, the first confirmed detection of bat XRV, the Hervey pteropid gammaretrovirus (HPG), took place in the feces of black flying fox. Researchers have also indicated that bat restriction factors play an important role in establishing a relationship between retroviruses and bats.

Role of bats in cross-species transmission

Cross-species transmission of retroviruses between different mammals is common. Bat retroviruses are thus no exception. Gamma and betaretroviruses, also referred to as class I and II ERV, can be transmitted to other animal species.

Analysis of thousands of ERVs across 69 mammalian genomes indicates that bat retroviruses have a major role as hosts of mammalian retroviruses. Being the only mammal that can fly, bats are of increased importance in spreading mammalian viruses. Bats can provide a hypothetical transmission route because flight allows them to cross physical barriers impenetrable to other mammals. Bats are also capable of traveling for long distances as well as can cross several biogeographical areas.

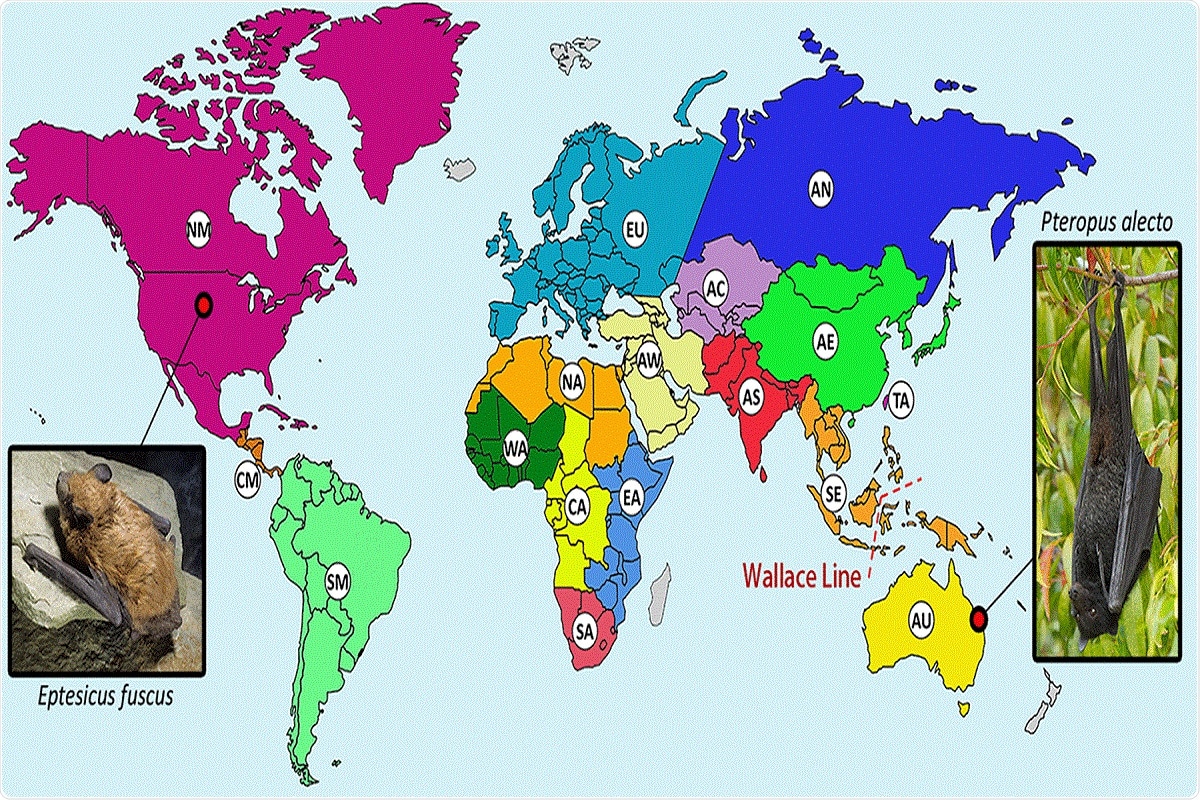

One such example is the black flying fox, the host of HPG whose habitat ranges across the oceanic faunal boundary known as the Wallace line. HPG is a close relative of gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV) and koala retrovirus (KoRV), whose hosts are koalas and gibbons that originate in Southeast Asia and Australia and thus are separated by the Wallace line.

FIG 2 Distribution of bats from which retroviral sequences have been reported. Geographical regions hosting bat species with reported retroviral sequences are separated by color and labeled as follows: AC, Central Asia; AE, Eastern Asia; AN, Northern Asia; AS, Southern Asia; AU, Australia; AW, Western Asia; CA, Central Africa; CM, Central America; EA, Eastern Africa; EU, Europe; NA, Northern Africa; NM, Northern America and the Caribbean; SA, Southern Africa; SE, South East Asia; SM, Southern America; TA, Taiwan; WA, Western Africa. Regions in gray have not had reported bat retroviral sequences. A biogeographical boundary, the Wallace line, is indicated by the red dashed line. The hosts of two confirmed bat exogenous retroviruses (XRVs), the black flying fox (Pteropus alecto), and the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) are pictured. “Black Flying Fox - Pteropus Alecto” by Andrew Mercer available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Black_Flying_Fox_-_Pteropus_alecto_-_(IMG_4883).jpg under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0. “Big Brown Bat” by John MacGregor available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Big_brown_bat_crawl.png under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0.

Are bat retroviruses a threat to humans?

The retroviruses that affect humans are HIV and HTLV, although other retroviruses also infected the ancestors of humans. Recent bat XVRs include the delta and gammaretroviruses. HTLV is a deltaretrovirus, whereas Gammaretroviruses are not known to infect humans.

While no evidence of infection has been found with Eptesicus fuscus deltaretrovirus (EfDRV,) its close relatives HTLV and bovine leukemia virus (BLV) have the potential to infect humans. BLV utilizes the CAT1 receptor to gain entry into the cells and has been found to replicate in human cells in vitro, while HTLV is a well-known human pathogen.

HPG is a close relative of GALV and KoRV and, like them, utilizes the PiT-1 receptor to gain entry into the cells. HPG is capable of infecting human cells in vitro as well as release viral particles into the cell. However, this does not ensure that the virus can cause disease in humans.

Interspecies transmission of retroviruses can occur through various routes, such as food contamination by urine or feces, or blood. It can thus be concluded that the transmission of retroviruses from bats to humans requires fulfillment of various conditions and most often takes place via an intermediate host.

Conclusion

Thus, it can be concluded that transmission of retroviruses from bats to humans is not yet very common. But continuous surveillance of bats should be carried out to identify any novel retrovirus and investigate their biological and infectious property, which will help determine its proactiveness in zoonotic spillover. Current challenges in the study of bats and the isolation of viruses should be overcome to gain insight into the retroviruses capable of transmission to humans and provide preventive measures against them.