By examining results from reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing and the United Kingdom's national coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection Survey that took place in July, these researchers have discovered that those living in major urban areas or urban towns/cities, more deprived households, or the northern areas of England were most likely to test positively for COVID-19.

Study: Monitoring populations at increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the community. Image Credit: Zigres / Shutterstock.com

Study: Monitoring populations at increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the community. Image Credit: Zigres / Shutterstock.com

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

About the study

More than four million RT-PCR results from the cheek and nose swabs of nearly 500,000 individuals were examined and evaluated against 60 screening variables that could potentially identify an increased risk of testing positive including occupation, travel, social contacts, and use of face coverings.

Thirteen variables were then eliminated due to the likelihood that the subjects' prior behaviors or answers would be affected by infection, including social contacts and frequency of shopping. The eight 'core' variables that the statistical analysis focused on included sex, ethnicity, age, geographical region, rural/urban classification, household size, deprivation, and whether or not multiple generations of a family lived in the same household.

Logistic regression models were used to discover associations with these eight core variables. Age is a non-linear effect and was incorporated using a restricted natural cubic spline. This resulted in combined estimates at ages 10, 25, 40, 55, and 70.

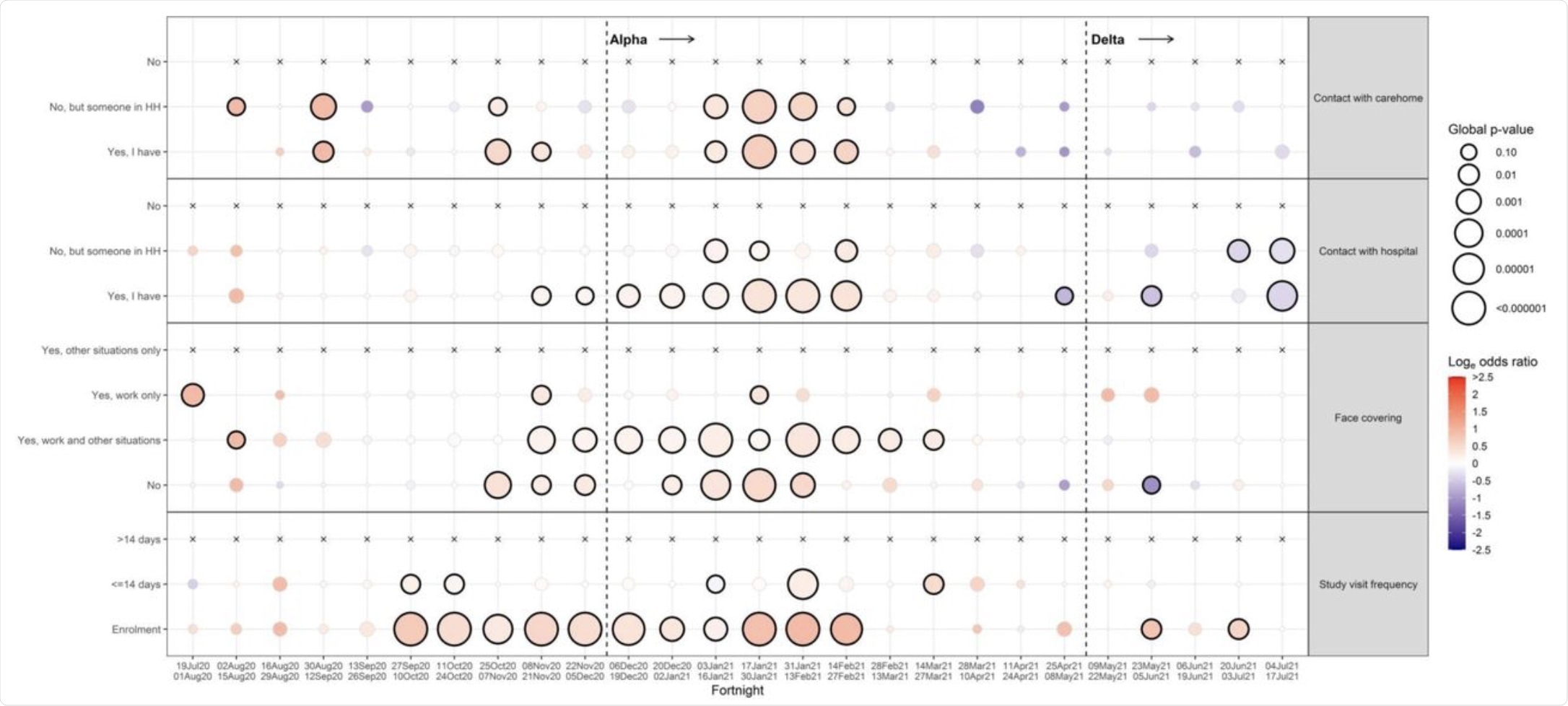

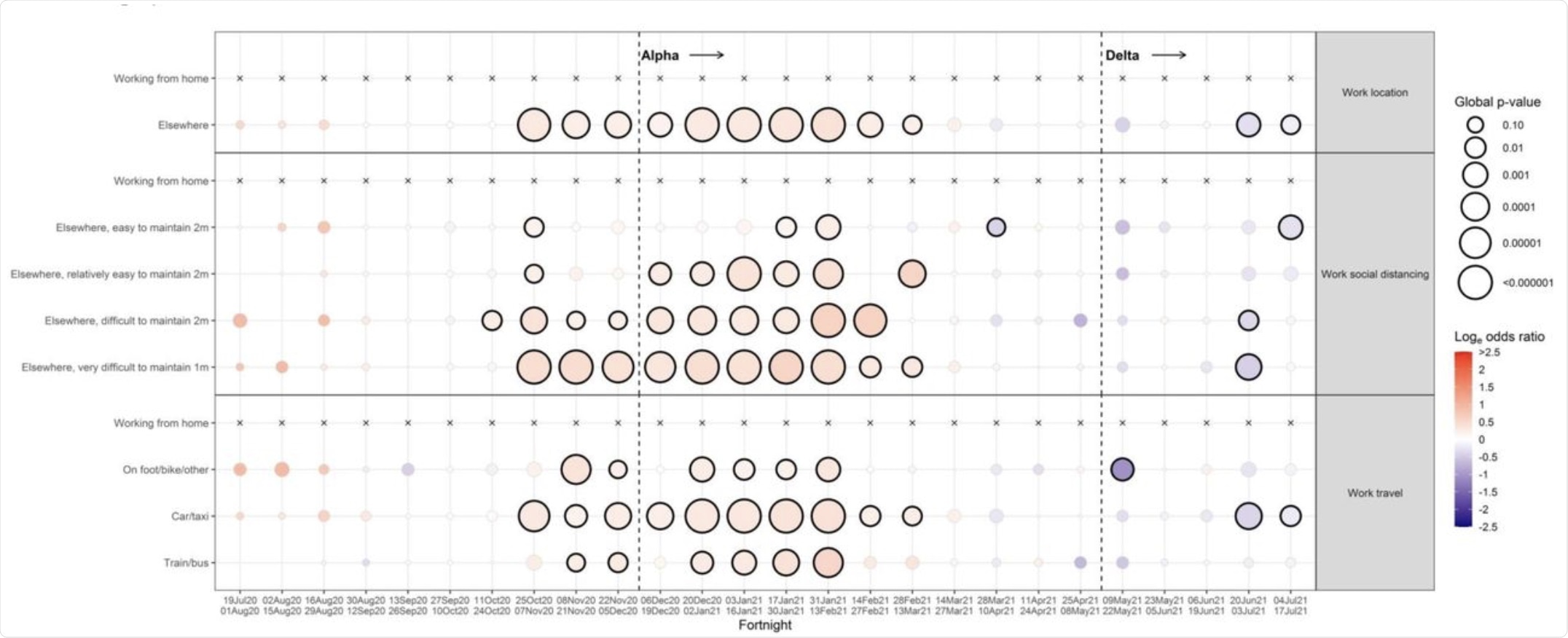

After examining interactions between the core values, each of the 47 screening variables was added individually to the core model. Effect sizes with a global statistical significance of under 0.05, or any test where p<0.001 was included in the final model.

Based on the significance and persistence of these effects, the screening variables were split into 5 categories, from ‘Never’, where no statistically significant effect size was discovered, to ‘Persistent’ where a statistically significant effect remained across the duration of the study.

Study findings

Several of these screening variables were very strongly associated with an increased probability of receiving a positive result on a COVID-19 test. Unsurprisingly, contact with anyone who had recently had COVID-19, as well as anyone who was currently self-isolating both consistently predicted higher odds of a positive test, as did the belief that one currently or recently had COVID-19.

Contacts.

Contacts.

Employment, especially within care homes and healthcare facilities, also showed a significant association with positive COVID-19 results, while information technology (IT) workers had consistently lower odds. Those traveling to work showed a greater risk than those working from home. However, in an unexpected turn, those traveling by train or bus were less likely to contract the disease than people traveling by car or taxi.

Work and employment.

Work and employment.

Another non-intuitive factor is smoking, which was associated with a lower risk of COVID-19. This effect was first reported in August and is likely due to nicotine interference with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, which prevents the virus from entering cells.

While long-term health conditions do increase the risk of serious complications from COVID-19, there is no evidence from this study that suggests that those suffering from such conditions are at greater risk of contracting it. This is likely due to the fact that at-risk groups are more likely to be isolating or shielding, which could interfere with the result.

The core variables most associated with a positive test result changed over time. During the initial waves of the disease, ethnicity showed the greatest effect, with those of non-white ethnicity showing increased odds of contracting COVID-19 as compared to those of white ethnicity. As the disease expanded further, geographical region, rural/urban environments, and household size showed greater effects. Northern Ireland, Wales, and northern England, for example, showed an increased chance of positivity, whereas urban environments and larger household sizes were similarly a risk factor.

As winter set in, age and deprivation became larger factors, likely as the colder weather began to lower the efficiency of immune systems. The geographical odds shifted during this time as well, with the south of England and London rising in risk as the Alpha variant began to take hold.

During the summer of 2021, positivity rates rose across the board as restrictions were loosened. Moreover, it was revealed that sex played a role in that men were more likely to contract the disease compared to women. The age most associated with a positive test also changed, with 16-30 year olds now showing the largest risk. In general, there was very little interaction between the effects of the core variables, and most seem to act independently.

Conclusion

The authors hope to use this screening process more in the future. Potentially, it could allow up-to-date understanding of the current spread of SARS-CoV-2 and help identify those who are most at risk. This could be used to target public health messaging and testing facilities to the right groups, as well as warn those most likely to get the disease.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Pritchard, E., Jones, J., Vihta, K., et al. (2021) Monitoring populations at increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the community. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.09.02.21263017. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.02.21263017v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Pritchard, Emma, Joel Jones, Karina-Doris Vihta, Nicole Stoesser, Prof Philippa C. Matthews, David W. Eyre, Thomas House, et al. 2022. “Monitoring Populations at Increased Risk for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Community Using Population-Level Demographic and Behavioural Surveillance.” The Lancet Regional Health - Europe 13 (February): 100282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100282. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666776221002684.