The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) caused a severe worldwide outbreak of COVID-19, which has caused the deaths of over 4.8 million. Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) ranging from social distancing, mask use in public spaces, and full-scale lockdowns, with travel bans at national and international borders, exerted a heavy toll on economic, educational, and social interactions.

In an attempt to obviate such restrictive measures, emergency use authorization (EUA) of several different COVID-19 vaccines was issued by federal agencies around the world. The earliest to be deployed were the Pfizer BNT162b2 and the Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccines.

Background

Recently, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a booster dose of the Pfizer vaccine to those who had been fully immunized with two doses 6-8 months earlier, provided that they were 65 years old or more, younger people between the ages of 18-64 years with a high risk of developing severe COVID-19, or those who are at an increased risk of COVID-19 due to institutional or occupational conditions.

Both vaccines are based on nucleic acid platforms that work by encoding the viral spike antigen for expression within the host cells. The Moderna vaccine contains a stabilized version of the ancestral spike antigen in the prefusion conformation, containing two proline mutations that prevent its switch to the fusion conformation.

This vaccine has been used in adults and adolescents with a good safety profile. It has proven to be tolerable and effective in reducing the incidence of COVID-19 in 93% of cases, according to a recent report analyzing vaccine efficacy at five months of follow-up.

Newer SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs) appear to resist neutralization by antibodies elicited by natural infection earlier in the pandemic with the wildtype strain of the virus, or by vaccine-induced antibodies. Antibody titers have been shown to wane over time, with some research suggesting that half the vaccinated population may not have detectable titers of neutralizing antibodies to the newly dominant Delta VOC.

Both these factors have likely resulted in a decline in vaccine efficacy, which nevertheless remains high. Overall, however, reduced vaccine effectiveness may be traceable to the high prevalence of the Delta variant, as observed in breakthrough infections among residents of long-term care facilities and frontline health workers.

Taken together, these factors have supported the potential utility of a booster dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. In the current paper, the immune response in individuals who received a single booster dose of the Moderna vaccine given about 200 days from the second dose of the primary vaccination regimen are reported, along with safety on the antigenicity and safety of this additional vaccine dose.

The study included two cohorts, about 300 each, aged 18-55 years and above 55 years. In each group, participants received either the vaccine at a dose of 50 micrograms (μg) or 100 μg, or placebo.

Study finding

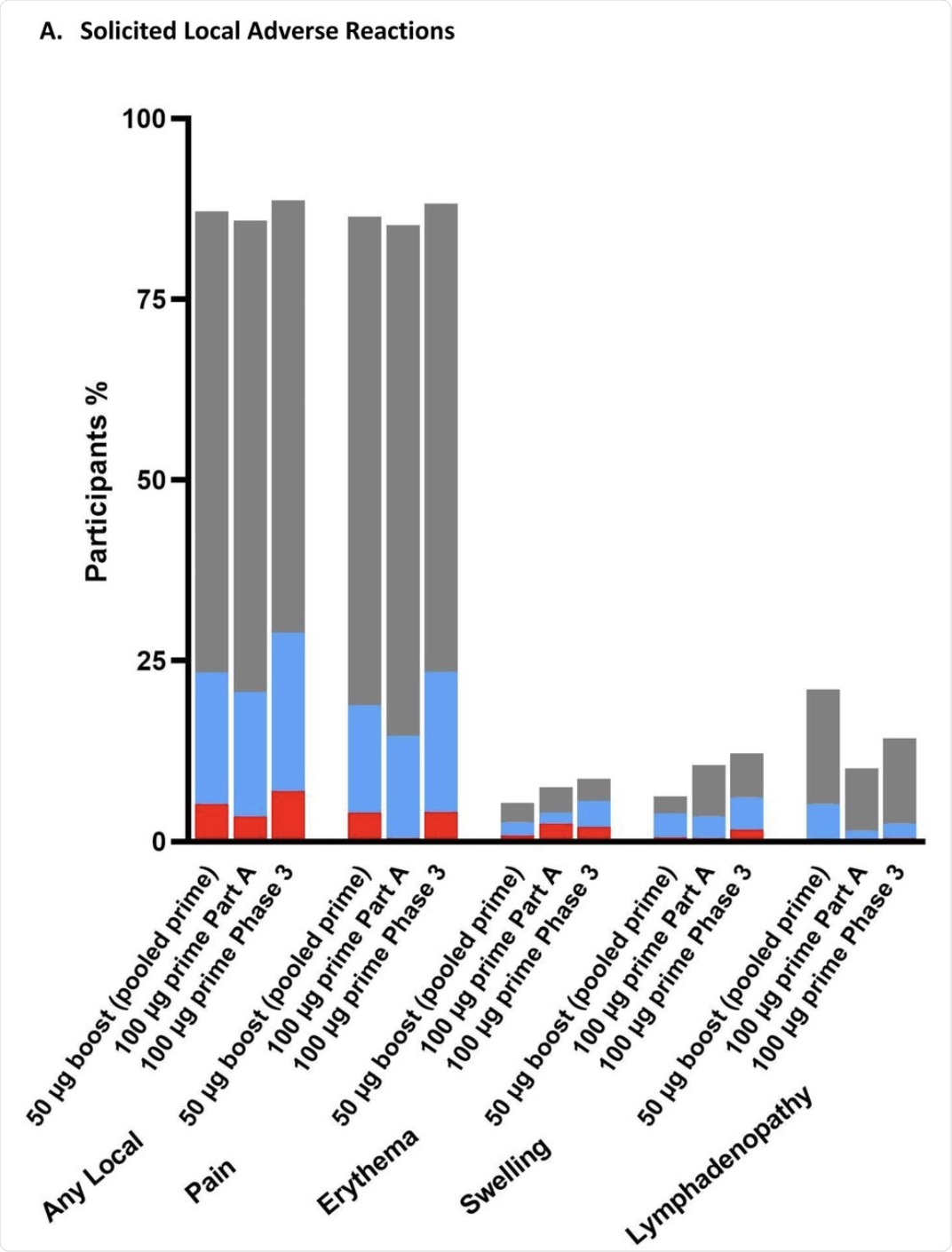

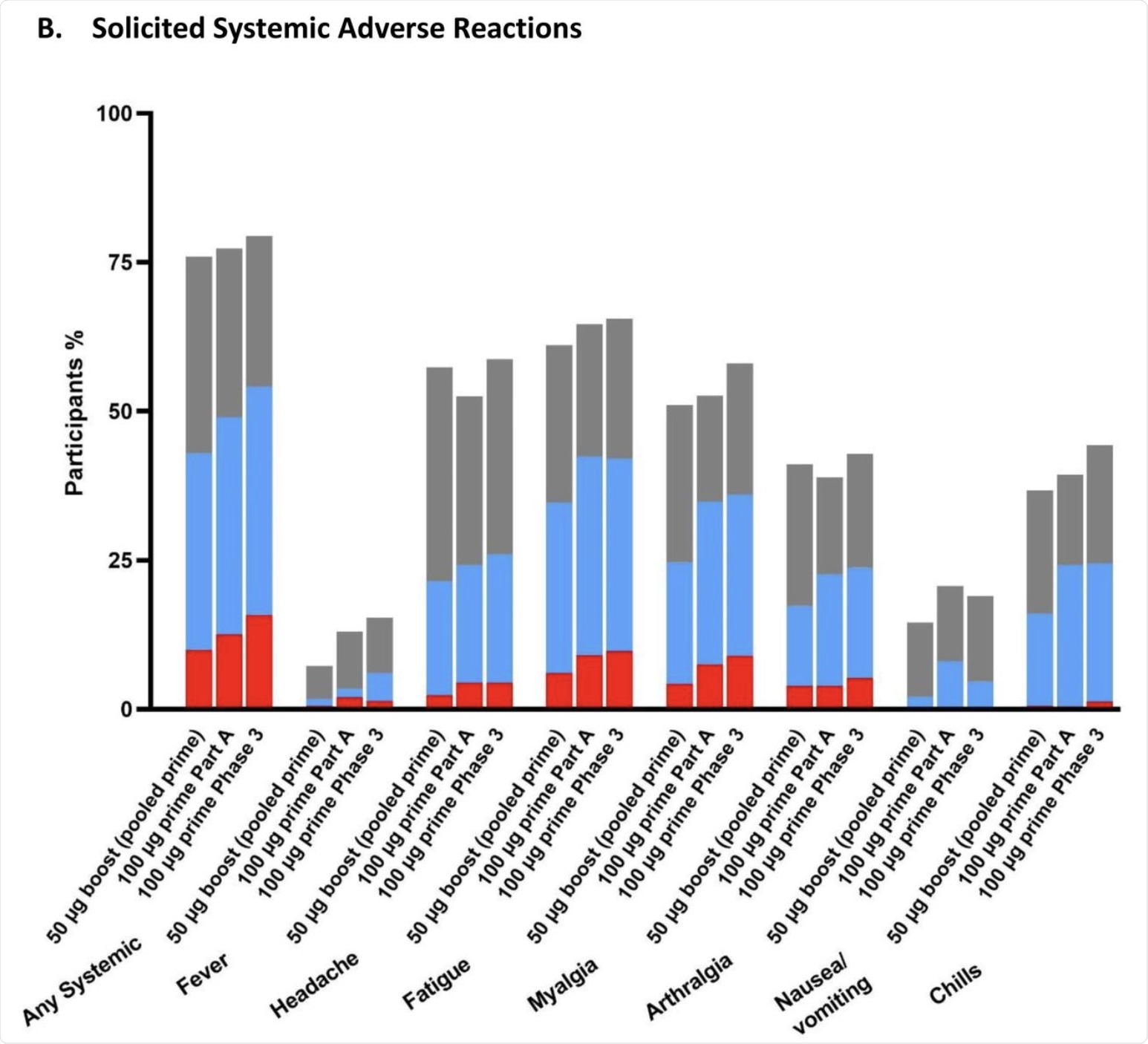

The researchers found that the booster dose did not cause a higher rate of local or systemic adverse reactions within seven days of the injection as compared to the placebo. This finding was independent of the dosage.

Most reactions were mild or moderate, with less than one in seven being grade 3. Furthermore, no grade 4 adverse events (AEs) were reported in the current study.

Pain at the injection site was extremely common and was reported in over 85% of recipients, irrespective of the dose. This reaction reached grade 3 in less than 5% of participants at either dosage.

Lymph node enlargement was seen at twice as high rates after the booster at either dosage as compared to those who had received two 100 μg doses of the vaccine.

Systemic reactions included headache, fatigue, and muscle pain, most of which were mild or moderate. Grade 3 systemic AEs included fatigue in 6% of the vaccine recipients. No serious AEs were reported at up to 28 days from the booster dose.

The percentage of participants in the Solicited Safety Set who reported local (A) or systemic (B) solicited adverse reactions is shown for 330 participants who received a booster dose of mRNA-1273 (50 μg) after a primary series of two doses of 50 or 100 µg of mRNA-1273 in Part B, 198 participants who received a booster dose of mRNA-1273 (50 μg) after a primary series of two doses of 100 µg of mRNA-1273 in Part B, and 14691 participants who received two doses of 100 µg of mRNA-1273 in the phase 3 COVE trial. The percentages of participants who submitted any data for the adverse event within seven days after the booster injection or the second dose during the primary series are shown.

The percentage of participants in the Solicited Safety Set who reported local (A) or systemic (B) solicited adverse reactions is shown for 330 participants who received a booster dose of mRNA-1273 (50 μg) after a primary series of two doses of 50 or 100 µg of mRNA-1273 in Part B, 198 participants who received a booster dose of mRNA-1273 (50 μg) after a primary series of two doses of 100 µg of mRNA-1273 in Part B, and 14691 participants who received two doses of 100 µg of mRNA-1273 in the phase 3 COVE trial. The percentages of participants who submitted any data for the adverse event within seven days after the booster injection or the second dose during the primary series are shown.

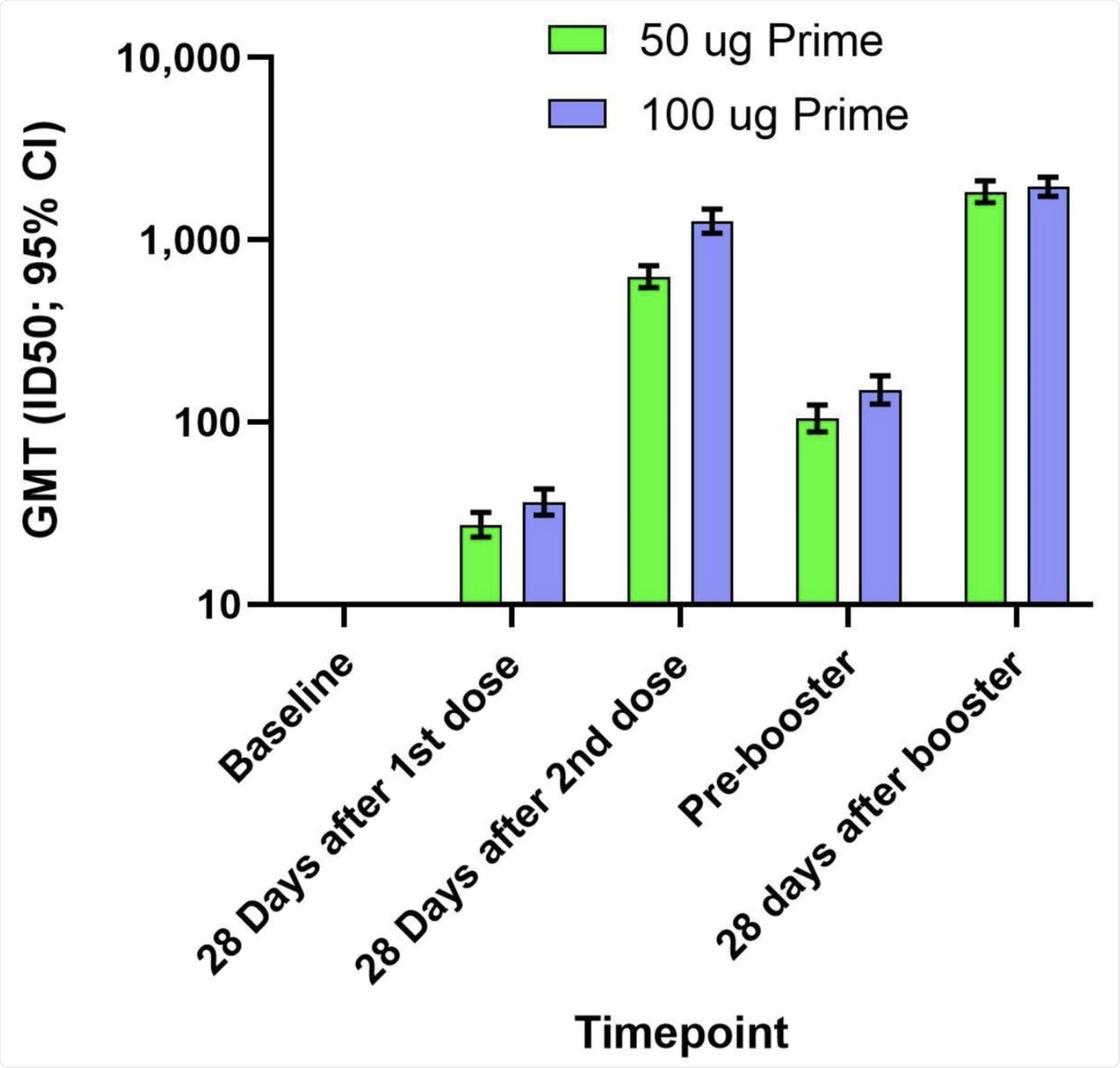

The booster dose was also immunogenic, with geometric mean titers (GMTs) of neutralizing antibodies against the D614G pseudovirus being almost 900 after two doses. The 100 μg group had GMTs twice as high as the 50 μg group. However, on the day before the booster dose, the titers had waned to a GMT of 150 and 100 in the 100 μg group and 50 μg group, respectively.

After the booster, the levels of neutralizing antibody rose to 2,000 in both groups. These were almost three times higher than the titers at 28 days from the second dose of the primary regimen in the 50 μg group, and almost twice that in the 100 μg group.

Serological responses were observed in over 93% and almost 99% of those who received a booster dose and after the two-dose primary vaccine regimen. When the Delta variant is considered, the neutralizing antibody titer before the booster was 42 and 800 before and 28 days after the booster, respectively, which is a 19-fold rise.

In the booster group, a four-fold rise from the baseline anti-Delta antibody titers was observed before the booster dose. However, titers against the D614G strain were 2.4-fold higher compared to the Delta variant, which reflects the trend seen after primary immunization as well.

The geometric mean titers (GMTs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) against the D614G virus for serum samples collected in Part A at baseline, 28 days after the first dose of mRNA-1273, 28 days after the second dose of mRNA-1273, and in Part B before the booster injection of 50 µg of mRNA-1273 (Pre-booster) and 28 days after the booster injection. Antibody values in the pseudovirus assay reported as below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ; 18.5) were replaced by 0.5 x LLOQ. Values that were greater than the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ; 45118) were changed to the ULOQ if actual values were not available. 95% Confidence Intervals were calculated based on the t-distribution of the log-transformed values or the difference in the log-transformed values for GMT, then back transformed to the original scale.

The geometric mean titers (GMTs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) against the D614G virus for serum samples collected in Part A at baseline, 28 days after the first dose of mRNA-1273, 28 days after the second dose of mRNA-1273, and in Part B before the booster injection of 50 µg of mRNA-1273 (Pre-booster) and 28 days after the booster injection. Antibody values in the pseudovirus assay reported as below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ; 18.5) were replaced by 0.5 x LLOQ. Values that were greater than the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ; 45118) were changed to the ULOQ if actual values were not available. 95% Confidence Intervals were calculated based on the t-distribution of the log-transformed values or the difference in the log-transformed values for GMT, then back transformed to the original scale.

Implications

The results of this study indicate the safety of a 50 μg booster dose of the Moderna vaccine when given 6-8 months after a primary vaccine regimen at either 50 or 100 μg of the vaccine. The absence of serious systemic AEs is an encouraging sign.

The increased neutralizing capacity against the D614G-spike-bearing pseudovirus at 28 days from the booster compared to titers at a similar time point from the second dose suggests that the booster dose stimulated memory B-cells, thus resulting in a strong immune memory response. The response was strongest with the 100 μg booster, probably because the assays used have different dynamic ranges.

At six months after full vaccination, the neutralizing antibody titers against the Delta variant were lower than at 28 days. In half the cases, neutralizing antibodies were undetectable. However, at two weeks from the booster dose of 50 μg, the anti-Delta antibody levels rose to the same level as anti-D614G antibodies had risen at 28 days from the second dose.

“Just as booster mRNA-1273 stimulated nAb [neutralizing antibody] levels against the original strain, a booster injection of mRNA-1273 was able to broaden and increase nAb levels against the Delta variant, highlighting the critical benefits of mRNA-1273 booster dose.”

The authors of the current study suggest that this route could result in long-term vaccine efficacy and a return to neutralizing capacity against multiple circulating and newly emerging variants. A third dose of the booster could enhance protection against the Delta variant, in particular, which is causing havoc across much of the world.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Chu, L., Montefiori, D., Huang, W., et al. (2021). Immune Memory Response After a Booster Injection of mRNA-1273 for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.09.29.21264089. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.29.21264089v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Chu, Laurence, Keith Vrbicky, David Montefiori, Wenmei Huang, Biliana Nestorova, Ying Chang, Andrea Carfi, et al. 2022. “Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2 after a Booster of MRNA-1273: An Open-Label Phase 2 Trial.” Nature Medicine 28 (5): 1042–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01739-w. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01739-w.