The COVID-19 pandemic has caused over 4.8 million deaths to date, with over 240 million reported cases. This sheer volume of human casualties, coupled with the damage to the world economy and the psychological stress of long-term restrictions on social interactions, have spurred an intensive effort to develop safe and effective vaccines against the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

With the rollout of several vaccines based on adenovirus vector or nucleic acid platforms, over 48% of the global population has already received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Despite these efforts, most of the world’s population remains at risk and is likely to remain so until 2023. In fact, some scientists estimate that at current rates, it may take up to five years to achieve 70-80% immunity.

The current study explores the dynamics of family transmission of the virus. The data from this study is expected to help determine vaccination strategies in situations of vaccine shortages.

The current study used data from Swedish national registries to compare transmission within families with varying numbers of immune individuals. Furthermore, the authors also used this information to compare the risk in settings with different sources of immunity including natural infection, one dose of the vaccine, or two doses (complete vaccination).

Study findings

The current study included over 800,000 families and approximately 1.8 million individuals. A family of two, neither of whom were immune, was the most common family; however, all configurations were identified. The sample was equally split between the sexes.

As the number of immune family members increased, the mean age went down compared to the non-immune individual at 27 and 52 years, respectively. The former type of family had fewer underlying conditions, a lower mean income, and a higher chance of being Sweden-born.

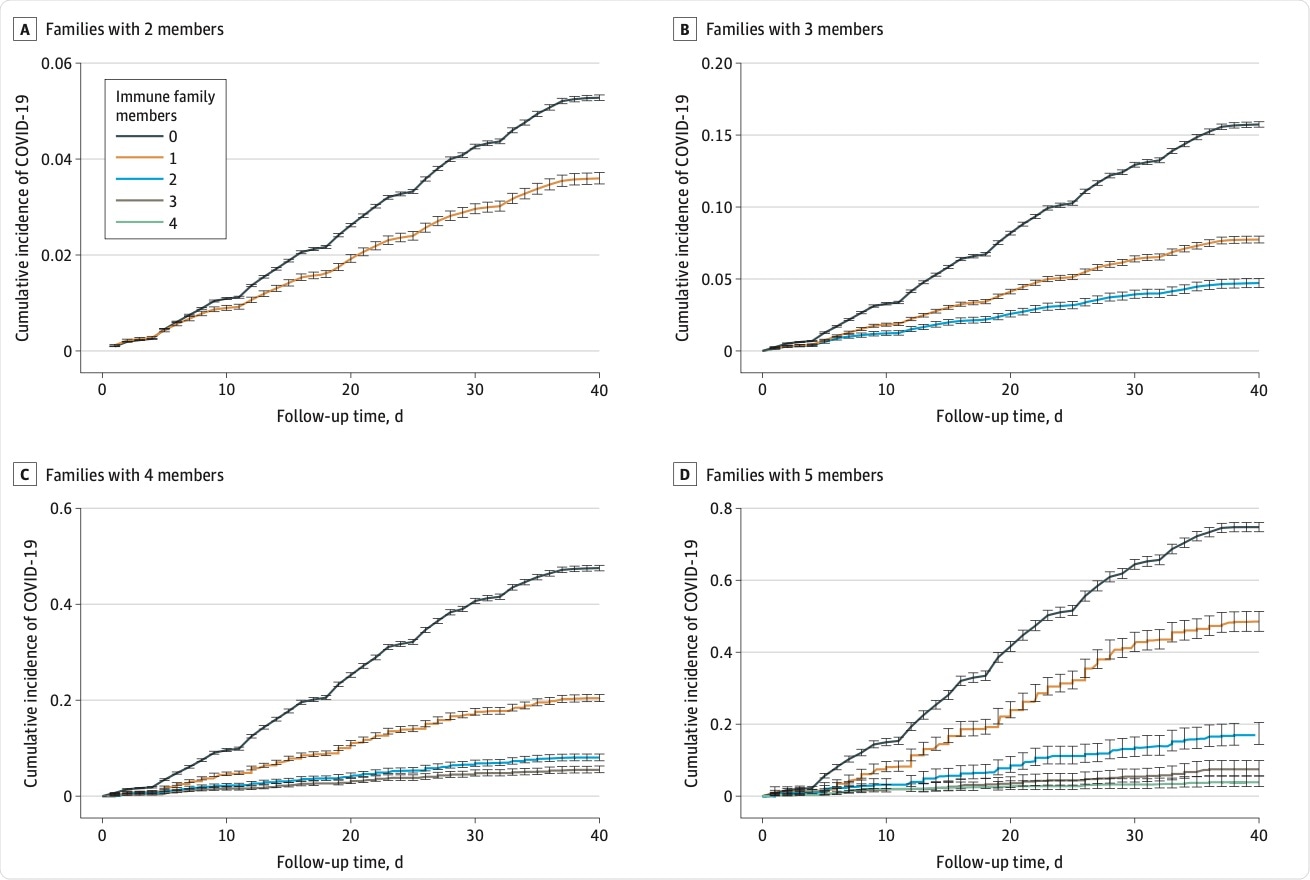

Over a total follow-up period of over 100,000 years, a diagnosis of COVID-19 was made in about 89,000 of non-immune individuals within a mean of 26 days. The number of immune family members went down with the risk of acquiring the virus.

In families where only one member was immune, the risk of a non-immune family member getting the infection was 45% to 61% lower, regardless of the family size. With two immune members, the risk was reduced by 75% to 86%, whereas members in families with three immune individuals were protected against 91% to 94% of disease.

In five-member families with four immune members, the risk for the sole susceptible member was 97% lower. The risk did not change, even if a family member had severe COVID-19 and required hospitalization.

Risk of COVID-19 in families with two to five members.

Risk of COVID-19 in families with two to five members.

Implications

This study was carried out in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant, which comprised over 95% of cases at the time.

The researchers found that the risk of COVID-19 is reduced by 45% to 97% and is proportional to the number of family members who were immune to the virus. The source of immunity did not seem to matter. In this setting, it appears that vaccines are important in preventing the spread of the virus within a family.

The greater the number of family members with a history of COVID-19, the less the risk to the susceptible family members. Thus, families with two out of three immune members saw the remaining susceptible members being at an 86% lower risk, while for those with three or four immune individuals, the risk was up to 97% lower.

In other words, the absolute risk of infection was proportional to the number of susceptible relatives in the family. Thus, the susceptible family member had an absolute risk of infection of 3% to 5% in the largest family with four or more members.

Conversely, the relative risk reduction was largest in large families. The absolute risk of infection, therefore, depends on the number of non-immune people in each family.

One dose of the vaccine protects against infection, illness, and death, according to earlier studies. However, it is unknown the extent to which a single dose of the vaccine can protect against family-based transmission. The current study adds to the sum of knowledge by demonstrating that a single dose appears to be as beneficial as two doses or that acquired by natural infection.

This would mean that in low-resource settings with a shortage of vaccines, these findings would help direct the vaccine where it is most needed. It is important to note that a single dose of the vaccine appears to be less protective against the Beta and Delta variants.

Importantly, these variants are also more transmissible than the Alpha variant, and the Delta variant is dominating the current surge. The results of the current study need to be followed up with data on the currently circulating variants.