The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in approximately five million deaths over less than two years since it was originally declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020.

The transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is the virus responsible for COVID-19, has led to restrictions on movement and social/economic activity in an attempt to reduce the rate of infections. While such measures have consistently restricted the spread of the virus, they are not definitive in their effect and lead to other devastating consequences such as the economic fallout and disruption of necessary and fundamental human interactions.

Vaccination is widely perceived to be the way out of this impasse, and the emergency use authorization of the first COVID-19 vaccines was followed by their mass deployment, subject to availability, in the most high-risk groups of the population. However, the humoral response elicited by these vaccines is known to wane over time, thus jeopardizing complete protection against new or repeat infections.

A new study published on the preprint server medRxiv* discusses the durability of the immune response following natural infection or vaccination. Earlier papers have described the development of the neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2, both in terms of titer and functional effect. The results of this study show that the neutralizing response is related to the severity of disease, with lower titers being linked to the need for oxygen supplementation in COVID-19 patients.

The antibody response shows a high level of diversity between individuals, and some individuals have detectable antibodies in their blood for up to 50 days later. The current study found that modeling the available data on antibody titers over time could help provide information on how long the response would last, and how these were related to the antigenic stimulation.

About the study

The researchers monitored neutralizing antibody titers with a model that showed antibody expansion and contraction, which was adapted from its first deployment for studying the Ebola virus infection. Both short-lived and long-lived antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) were employed as parameters in the current model.

When the neutralization efficiency is a correlate of the circulating functional antibodies, antibody kinetics can be expressed by including antibodies from both types of ASCs, with the antibody decay rate. Further modeling was used to extract any potential correlations between the model parameters and disease severity.

The researchers found that the model was adequate to explore antibody kinetics, predicting that the titer changed fold-wise with disease severity for short-lived ASC antibodies. This was followed by an exponential decline. Notably, the half-lives were not associated with severity, which is likely because these cells have a half-life of <5 days.

In the second phase, the model showed longer persistence of antibodies due to long-lived ASCs that produce a smaller but more sustained peak. The half-life of these cells remains undetermined but is more than 450 days. The key contribution of these cells is shown by the poor fitting seen with another model that did not incorporate their share, which indicates that both types of ASCs are involved.

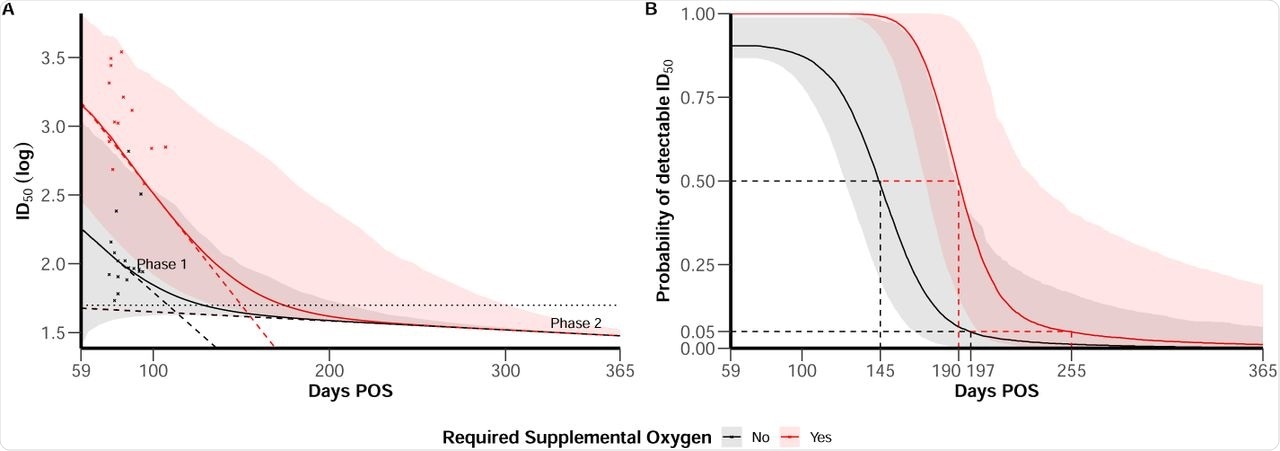

The duration of the detectable antibody response was modeled, showing that severe disease was correlated with a longer period of protection. When the long-lived ASC contribution was factored in, severe and all other grades of disease were correlated with 175 and 130 days of protection, respectively, beginning from symptom onset. Inter-individual variability is significant, and protection may last up to almost a year with severe disease, and up to >200 days with the non-severe disease.

(A) ID50 trajectories for individual with mean characteristics according to disease severity (severe in red vs. non-severe in black), 95% confidence bands account inter-individual variability. Horizontal line represents the limit of detection at ID50 = 50. Dashed line materialise the slope of the bi-phasic decline of ID50. Red and black crosses represent available data after 59 days post symptom onset (POS) in the dataset for severe and non-severe individuals. (B) Probability of detectable ID50 along time post symptom onset according to disease severity (severe in red vs. non-severe in black). Plain line represent the median behavior and 95% confidence bands account for both uncertainty in parameters estimation and inter-individual variability.

(A) ID50 trajectories for individual with mean characteristics according to disease severity (severe in red vs. non-severe in black), 95% confidence bands account inter-individual variability. Horizontal line represents the limit of detection at ID50 = 50. Dashed line materialise the slope of the bi-phasic decline of ID50. Red and black crosses represent available data after 59 days post symptom onset (POS) in the dataset for severe and non-severe individuals. (B) Probability of detectable ID50 along time post symptom onset according to disease severity (severe in red vs. non-severe in black). Plain line represent the median behavior and 95% confidence bands account for both uncertainty in parameters estimation and inter-individual variability.

Implications

This important study reveals the essential contribution made by neutralizing antibodies from long-lived ASCs in conferring protection against reinfection. The two phases of the decline of the antibody response show that both short- and long-lived ASCs participate in protective immunity. The antibody titer peaked at higher levels in individuals with severe disease.

Disease severity did not correlate with the half-life of either short- or long-lived ASCs, however, indicating that these remained constant. This indicates that antibody titers differ with severity in the acute phase of the disease, while long-lived ASCs are found to be equally active, independent of disease severity.

In other words, the neutralizing antibody response to natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 is more durable than earlier studies have indicated. Further exploration of the way functional antibody titers change over time is urgently required, using a large study sample, so as to detect other factors that impact this response and to arrive at a more accurate estimate of antibody-mediated protection.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.