Monitoring of post-vaccination adverse effects has shown increasing numbers of reports of menstrual changes in women who received the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine. A new study published on the preprint server medRxiv* reports on the incidence of this adverse effect, concluding that there is no evidence for such an association, while not ruling out the potential for detection of such a link with larger studies.

The monitoring system called Yellow Card has received many reports from women with alleged changes to their menstrual cycle following vaccination with a COVID-19 vaccine. However, most of these women also reported that their period returned to normal within a single cycle. There is also no observed evidence of disrupted female fertility.

In order to assess the validity of such concerns, the current study included over 1,200 women with a menstrual diary who had also recorded the dates of vaccination. Earlier studies on the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine have shown that periods may become heavier or irregular in such individuals, though viral infection itself, even with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), can also cause such changes.

The pathogenesis of this phenomenon may involve immunostimulatory mechanisms that may alter the hormonal cycle. Alternatively, immune cells in the endometrium could be stimulated, thus causing the observed changes by affecting the proliferation and shedding of the tissue.

The cohort tracked in this study is likely to be biased towards those who noted a change in their cycles after vaccination. Therefore, the investigators are currently also tracking another cohort who were already recording their cycles before vaccination. The current study may help, however, to tease out a preliminary hypothesis about a causal link.

Study findings

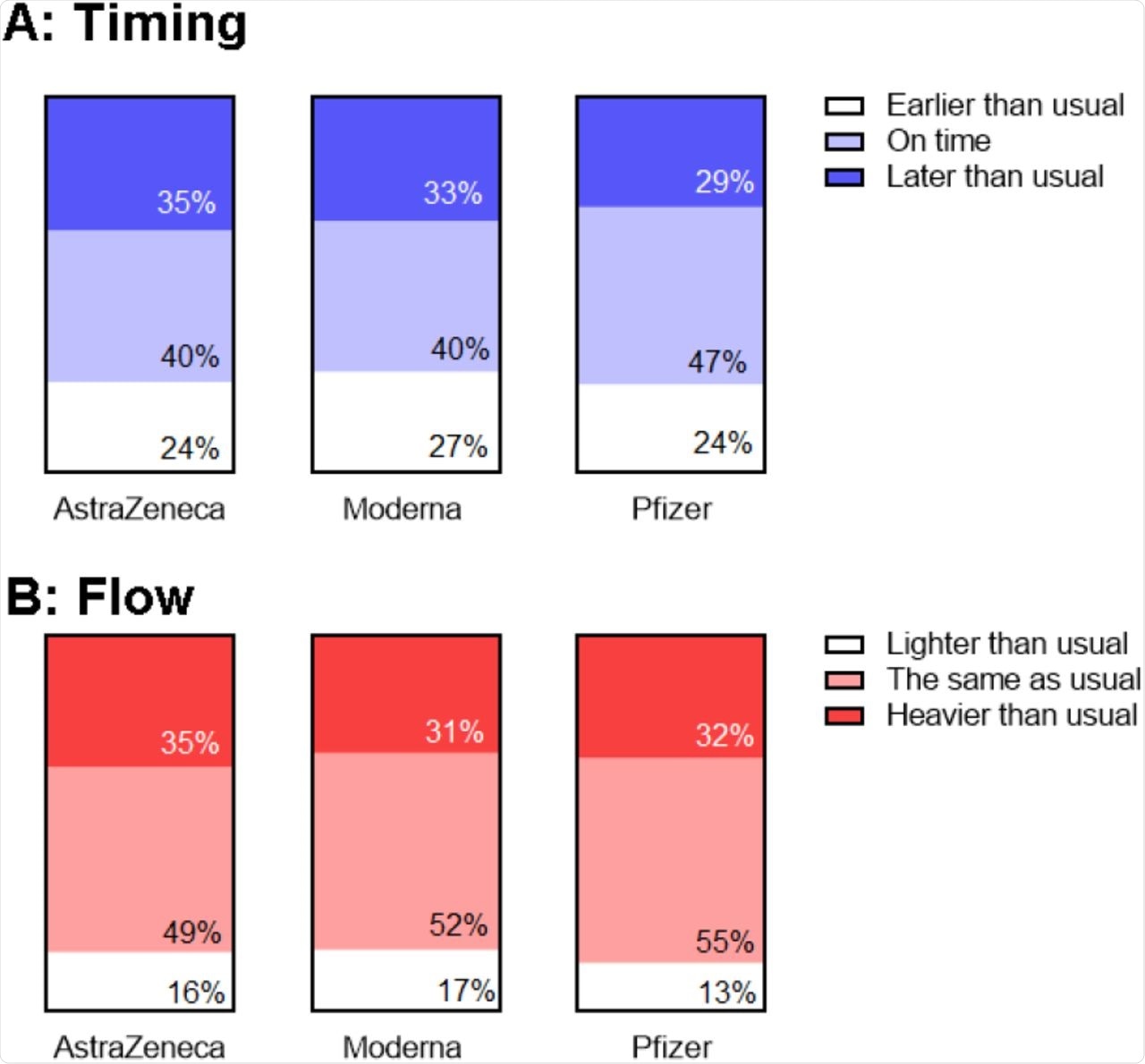

Despite the use of different vaccines, there was no obvious correlation between the brand and the presence or type of menstrual alteration in the subsequent cycle. Those who were on hormonal contraceptives were at a greater chance of such changes. Since sex hormones levels are maintained at a low but uniform level in those on oral contraceptives, this could rule out the association between vaccination and levels of sex hormones.

The time of vaccination was not clearly linked to the timing or flow pattern of the next period. The difficulty in finding a clear association partly lies in the sheer variety of changes reported in the period.

There have been many proposed mechanisms for changes in menstruation following COVID-19 vaccination, such as vaccine-induced delay in ovulation or disruption of ovulation. This would lead to a longer cycle than usual.

When considering those who were not on hormonal contraception, vaccination timing apparently appeared to be related to the timing of the next period in those who received the vaccines on pre-ovulatory days, on which less than five people had been vaccinated, and those who were already overdue, the authors found that

This was, however, negated when this association was found to be due to the effect of vaccination on the expected day of periods or the previous day. Taken together, this indicates that these women were already at a high risk of having delayed periods before taking the vaccine. Overall, the timing of the vaccine was not found to be related to the flow of the next period.

After the second dose, the same trends, or lack thereof, were observed. Most women did report the same kind of changes following both doses. This implies the effects of genetic or individual factors are predominant in vaccination-related alterations in period timing or flow.

Association between reports of changes in timing (A) and flow (B) following first and second vaccine dose.

Association between reports of changes in timing (A) and flow (B) following first and second vaccine dose.

There is an apparent concern about the risk of period delay following vaccination in women who already have polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) or endometriosis. Many women have this concern, stating that with already heavy, painful, and/or difficult periods, they hesitate to take the vaccine for fear of aggravating these symptoms.

In the current study, however, such a trend was not observed in women who had already been diagnosed with a pre-existing condition of the uterus or menstrual abnormality, including those with a history of menorrhagia, abnormal bleeding, uterine fibroids, endometriosis, or PCOS. However, a borderline significance was observed after adjusting for multiple factors.

In particular, women who had heavy or abnormal bleeding or had fibroids were found to have a slightly greater chance of having an earlier period, while a delay in the next period is somewhat more likely in those with a history of PCOS.

Implications

The results of the current study do not find any observable associations between the COVID-19 vaccination, the brand of vaccine, and menstrual timing. Delayed periods were reported mostly by women who were already heading for a late period at the date of vaccination.

People on hormonal contraception were at a greater risk for differences in the flow of their next period following vaccination, which rules out a hormonal etiology. The lack of a plausible biological mechanism to explain this mandates follow-up analysis to rule out reporting bias.

That is, since many women use hormonal contraceptives to control their menstrual flow, a heavier flow following vaccination may have led many of them to join the study, as compared to those who are not on such pills but also had heavier flow after taking the vaccine.

The explanation for the high degree of similarity between the changes observed after the first and second doses indicates that individual, including genetic, variation might explain a lot of these changes. Other potential reasons include the eight-week interval between doses, which could mean that whatever biological change followed the first dose, would still exert an effect by the time of the second dose, thus accounting for the similar side effects.

The lack of association between menstrual changes and pre-existing gynecologic disease should reassure women who fear that their condition will worsen after vaccination. People with endometriosis and PCOS did have a slight advancement and postponement of their periods, respectively, which must be followed up for validation. Until then, these findings should not contribute to vaccine hesitancy, especially since it is well-established that SARS-CoV-2 itself affects the menstrual cycle.

The current study does not fully determine the frequency of menstrual changes after COVID-19 vaccination as a result of its retrospective design that lends itself to recall bias. Instead, prospective studies should be done. Alternatively, already collected menstrual data that has been stored for other purposes could be mined to answer this question more accurately.

The authors recommend data from menstrual cycle tracking apps, both because of the volume of data logged over multiple cycles and the detail in which such data is stored. It is also important to note that the study participants were mostly British and that the study did not look at other vaccines like Sinovac or Sputnik V. Most of these other vaccines use a shorter interval between doses, which could lead to different side effects.

In conclusion, this study of 1273 retrospectively recruited participants was unable to detect strong signals to support the idea that COVID-19 vaccination is linked to menstrual changes. However, large, prospectively recruited studies may be able to find associations that we were not powered to detect.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources