When it comes to determining when vaccine boosters and pandemic policy interventions should occur, understanding the duration and effectiveness of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and vaccination is imperative. Researchers examined this in a large prospective cohort of UK healthcare workers undergoing routine PCR testing.

In real-world studies, the short-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines has been observed with a reduction in both symptomatic and asymptomatic infection, severity, and secondary transmission.

Over 69% of the UK population have received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, and the prioritized groups are six months past their second vaccine dose. The UK government has initiated the launch of booster vaccination to priority groups considering potential immunity waning and sustained high levels of community infections driven by SARS-CoV-2 variants.

A better understanding of vaccination schedules, vaccine effectiveness at longer intervals, potential variation in effectiveness by demographic factors, and history of SARS-CoV-2 infection is crucial to support global vaccination plans.

Study: Effectiveness and durability of protection against future SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by COVID-19 vaccination and previous infection; findings from the UK SIREN prospective cohort study of healthcare workers March 2020 to September 2021. Image Credit: NIAID

Study: Effectiveness and durability of protection against future SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by COVID-19 vaccination and previous infection; findings from the UK SIREN prospective cohort study of healthcare workers March 2020 to September 2021. Image Credit: NIAID

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

About the study

In a pre-print study, named SARS-CoV-2 Immunity and Reinfection Evaluation (SIREN), published on the medRxiv* server, authors assessed the effectiveness and durability of the immune response against future SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination from March 2020 to September 2021.

In this study, the participants undergo fortnightly SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, monthly antibody testing, and complete regular questionnaires. Further, the dosing interval was categorized as 'short' if dose-two was taken up to 6-weeks post-dose-one and 'long' if ≥6-weeks. Also, the cohort was classified as 'naïve' if the participants had no history of SARS-CoV-2 positivity and 'positive' if the participants had ever received a PCR positive or antibody result consistent with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The follow-up started on 07 December 2020 and continued until 21 September 2021. The follow-up end date for individual participants was either the date of primary infection (negative cohort), the date of reinfection (positive cohort), or the date of the last PCR negative test. The authors grouped the time to vaccination and divided follow-up time into unvaccinated and post-vaccination time intervals. Also, they grouped the time since primary infection into four time intervals: before primary infection (naïve), and then 3-9 months, 9-15 months, and ≥15 months after primary infection. The effectiveness and protection of vaccines from primary infection were calculated as 1-HR.

Key findings

The authors assigned 26,280 participants to the naïve cohort and 9,488 to the positive cohort at the analysis start time. The positive cohort mainly included young males from Black, Asian, and ethnic minority backgrounds, who worked in clinical roles and reported frequent exposure to COVID-19 patients. About 97% of the cohort had received two vaccine doses by the end of the analysis time: 78.5% BNT162b2 (BioNTech, Pfizer vaccine) long-interval, 8.6% BNT162b2 short-interval, and 7.8% ChAdOX1 (Oxford, AstraZeneca vaccine).

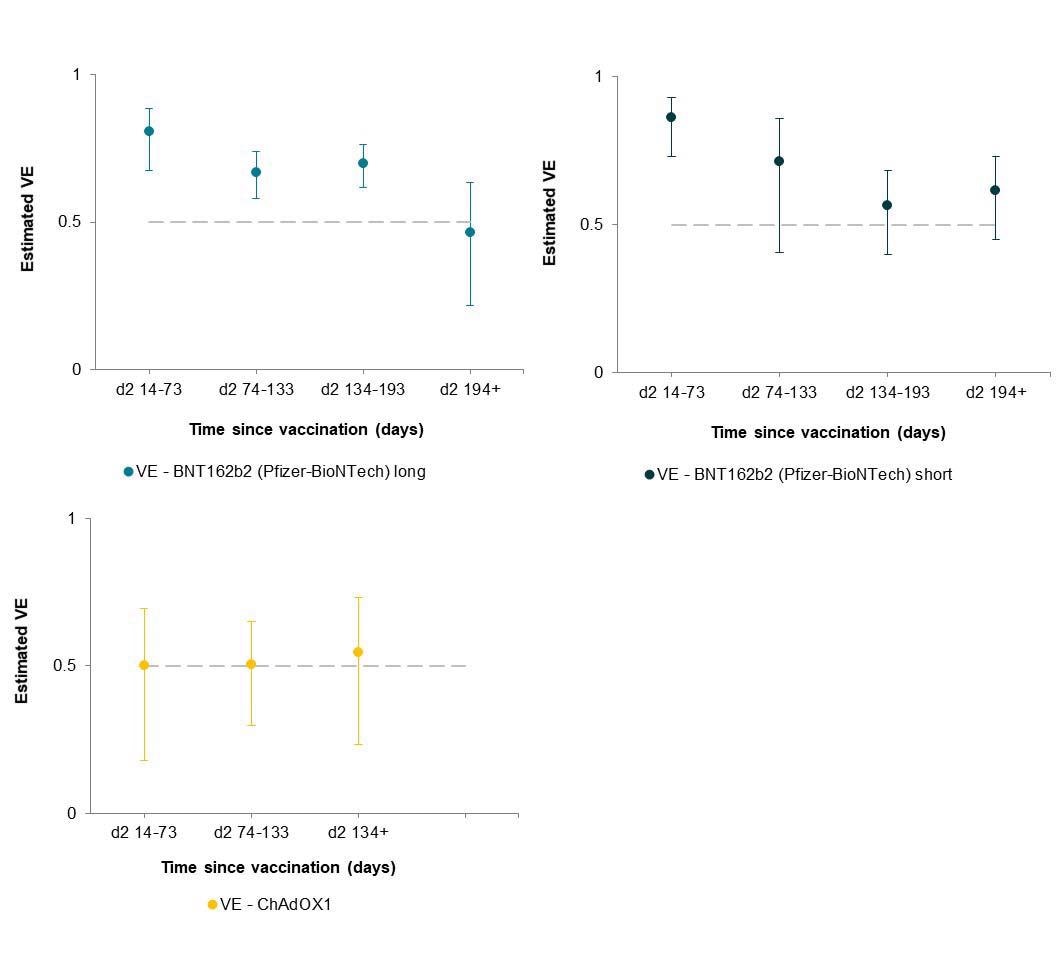

Adjusted Vaccine Effectiveness over time after two doses: BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) short and long interval and ChAdOX1 (combined short and long interval)

Adjusted Vaccine Effectiveness over time after two doses: BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) short and long interval and ChAdOX1 (combined short and long interval)

The overall adjusted vaccine effectiveness (aVE) against SARS-CoV-2 infection post-dose-two of BNT162b2 vaccine administered at a long inter-vaccine interval was 81% over the first two months. However, significant waning was found after six months with a VE of 46%.

Similar protection was observed for BNT162b2 dose two short-interval. However, the study data showed significantly lower protection from two doses of ChAdOX1 compared to BNT12b2. Since the period of waning coincided with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant being the predominant circulating strain, the reduced vaccine effectiveness against the Delta variant was reported.

The study also found evidence of waning of immunity from infection-acquired immunity in unvaccinated follow-up. Still, the protection remained consistently above 90% in participants who received two doses of vaccine, including those infected more than 15 months ago.

Conclusions

The findings of the study revealed that vaccination with two doses of BNT162b2, at a short or long-interval, induced high protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection (asymptomatic and symptomatic) in the short term; however, this protection waned after six months, when the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant became the predominant circulating strain.

The overall protection provided by two doses of ChAdOX1 was considerably lower than that given by BNT162b2. However, infection-acquired immunity boosted with vaccination-induced immunity remained high over a year after infection. Based on these observations, the authors recommend the strategic use of booster vaccines to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission in the population.

"Two doses of BNT162b2 vaccination induce high short-term protection to SARS-CoV-2 infection, which wanes significantly after six months."

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Effectiveness and durability of protection against future SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by COVID-19 vaccination and previous infection; findings from the UK SIREN prospective cohort study of healthcare workers March 2020 to September 2021 Victoria Jane Hall, Sarah Foulkes, Ferdinando Insalata, Ayoub Saei, Peter Kirwan, Ana Atti, Edgar Wellington, Jameel Khawam, Katie Munro, Michelle Cole, Caio Tranquillini, Andrew Taylor-Kerr, Nipunadi Hettiarachchi, Davina Calbraith, Noshin Sajedi, Iain Milligan, Yrene Themistocleous, Diane Corrigan, Lisa Cromey, Lesley Price, Sally Stewart, Elen de Lacy, Chris Norman, Ezra Linley, Ashley D Otter, Amanda Semper, Jacqueline Hewson, Silvia D'Arcangelo, The SIREN Study Group, Meera A Chand, Colin S Brown, Tim Brooks, Jamin Islam, Andre Charlett, Susan Hopkins, medRxiv, 2021.11.29.21267006; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.29.21267006, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.11.29.21267006v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Hall, Victoria, Sarah Foulkes, Ferdinando Insalata, Peter Kirwan, Ayoub Saei, Ana Atti, Edgar Wellington, et al. 2022. “Protection against SARS-CoV-2 after Covid-19 Vaccination and Previous Infection.” New England Journal of Medicine, February. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2118691. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2118691.