Gary: I am an epidemiologist in the Department of Genetics at Rutgers University. My research focuses on why people with a neurological disorder often also have a psychiatric disorder.

Since individuals with treatment-resistant epilepsy are at greater risk for psychiatric disorders, I have become interested in the factors associated with treatment-resistant epilepsy. I, and my collaborator at Columbia Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, have conducted a series of studies investigating the factors involved in treatment-resistant epilepsy.

Brad: I am a clinical epileptologist (epilepsy specialist neurologist) in the Department of Neurology at Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

I am interested in the intersection of epidemiology, epilepsy research, and health services research, in particular, understanding ways that we can provide quality epilepsy care in New Jersey. This project was one that I started during my epilepsy fellowship at Columbia University.

What is generalized epilepsy and why is optimized treatment so vital?

Idiopathic generalized epilepsy is an umbrella term that encompasses types of epilepsies in which seizures begin from both sides (hemispheres) of the brain. Patients with generalized epilepsy usually start having seizures in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood and they generally have normal childhood development and intelligence.

Compared with focal epilepsies (ones that originate from one part of the brain), there are fewer medications available to treat idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy surgery, which can be performed for patients with focal epilepsy who continue to have seizures despite treatment with medications, is not currently an option for patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Thus, there are fewer treatment options available for patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

What are seizures and how do they affect generalized epilepsy patients?

Seizures are the clinical manifestation of the electrical hyper synchronization of networks in the brain. Basically, abnormal brain wave activity spreads throughout the brain to cause a wide variety of neurological symptoms, depending on which part of the brain is affected by the seizure. This can range from body shaking, alteration of awareness, or staring spells, to many other manifestations.

For patients with generalized epilepsy, seizures often manifest as staring spells, body jerking, or generalized tonic-clonic seizures, previously known as “grand mal” seizures. These are life-threatening events with full-body stiffening, shaking, and loss of consciousness.

How do anti-seizure drugs work?

There are currently over 25 antiseizure medications in use at this time, which have different mechanisms of action. Many of these work on neuronal ion channels or neurotransmitters in the brain. In essence, they suppress seizures while the patient is taking them but require that patients take them diligently every day. However, these medications cannot “cure” a patient of having seizures and so often medications are required lifelong for patients.

What other treatments are there for patients who are unresponsive to anti-seizure drugs?

For patients with focal epilepsy (where seizures arise from one part of the brain), we can work with epilepsy neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists, and other specialists to develop a plan to perform surgery, that is, remove the part of the brain where seizures originate. Surgeons can also place implanted neurostimulator devices in the brain or chest wall, like a pacemaker.

However, because patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy have seizures that begin in both sides (hemispheres) of the brain, we cannot perform epilepsy surgery on them. For patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy, there are currently no other treatments available other than anti-seizure medications, which unfortunately do not always fully control seizures for all patients, especially those with difficult-to-treat epilepsy.

Image Credit: Jarun Ontakrai/Shutterstock.com

How did you combine electroencephalogram (EEG) data and clinical observations within a statistical model to determine if a generalized epilepsy patient would respond to drug treatment?

We were trying to determine which factors were associated with treatment-resistant generalized epilepsy. In our prior study, we only included clinical variables like Catamenial epilepsy, history of a psychiatric condition, and type of seizures. In that study, our model was able to discriminate between treatment-resistant and treatment-responsive epilepsy by 60%.

We wanted to improve on that and decided to include various EEG findings. In this new study, we found that combining clinical and EEG factors together increased our prediction to 80%.

How will these predictions help improve generalized epilepsy treatment and benefit patients?

Our prediction model can provide treating clinicians with additional information on their patient’s prognoses. By categorizing a group of treatment-resistant individuals with similar clinical or EEG findings, we hope that treatment regimens could be developed that work better for the people who continue to have seizures.

Clinicians can use our model by asking patients specific clinical questions and obtaining EEGs to better estimate their prognosis. Currently, we have few studies that help patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy understand their prognosis, or whether seizures will be controlled long-term. We hope future studies will provide additional ways to predict an individual’s prognosis.

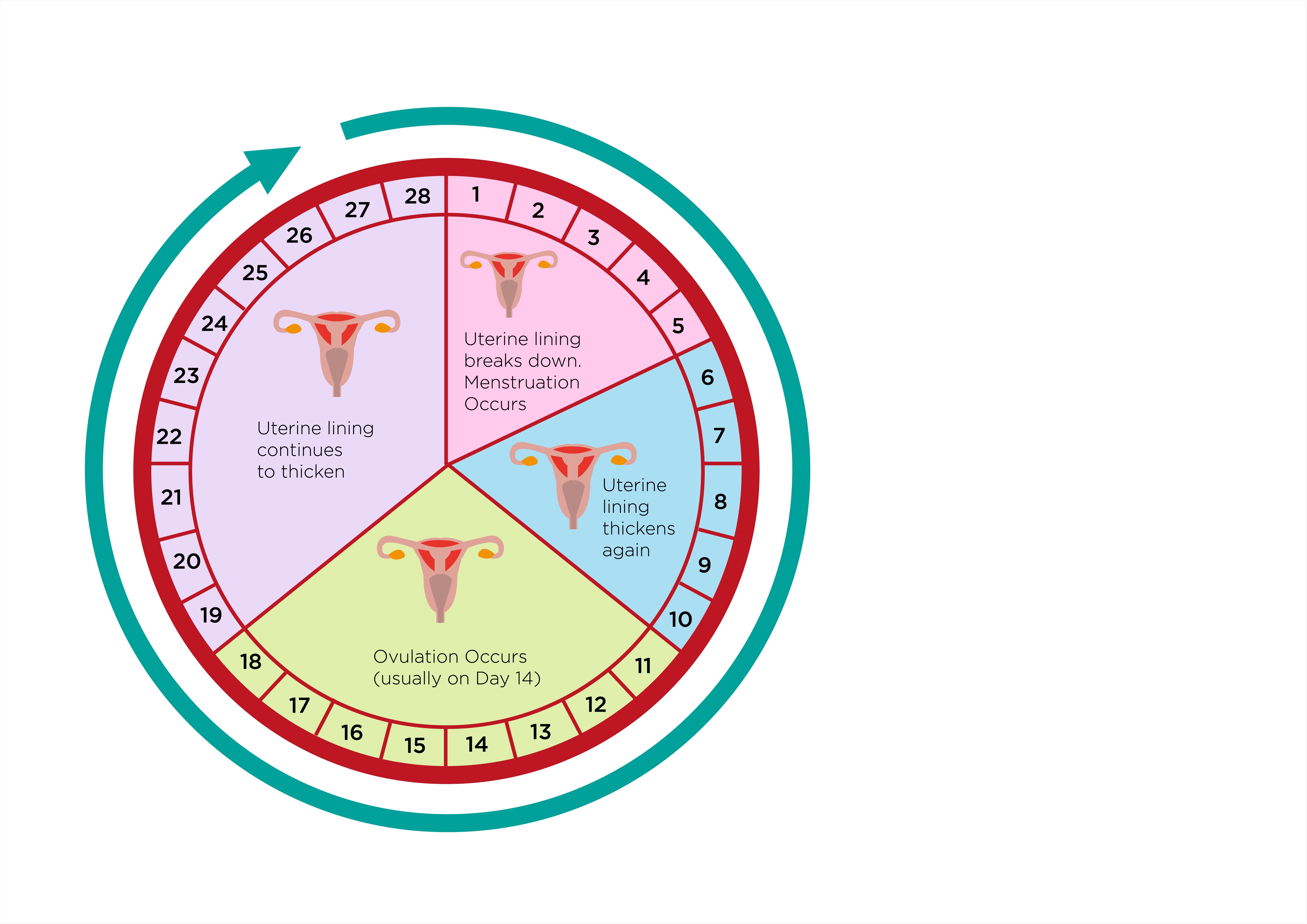

Please can you tell us about catamenial epilepsy and what your study and previous studies have shown regarding this particular type of epilepsy?.

Catamenial epilepsy is defined as when seizure frequency increases during certain times during the menstrual cycle. In our previous study (CLICK HERE), we found that women with generalized epilepsy whose seizures changed during the menstrual cycle were nearly four times more likely to have treatment-resistant epilepsy.

This was a surprising finding as this had not been previously reported in generalized epilepsy. In this new study, we again found this association suggesting that women with catamenial generalized epilepsy may represent a separate group with distinct causes. We hope that treatment studies could be conducted to find tailored treatment.

Image Credit: Crystal Eye Studio/Shutterstock.com

What has been the overall goal of your research and do you think there will be successful impacts?

Traditionally, we had few tools available to help us predict whether a patient will do well and remain seizure-free or continue to have seizures despite treatment with medications. Epilepsy patients want to know more about their prognosis, and any additional information we can give them about their disease is valuable.

Therefore, our overall goal for this research was to provide clinicians and their patients with better information about prognosis. This could help identify patients who need more aggressive treatments. Also, by identifying a group of treatment-resistant patients with similar causes, we hope that treatment regimens could be identified that work better in these individuals.

What is the next step for this research?

Based on our findings, we believe that clinicians should consider obtaining greater detail about a patient's different seizure types and whether they experience changes in seizure frequency with their menstrual cycle.

Also, they should consider more thorough EEG studies (longer duration including during sleep and assessed for certain patterns of abnormal electrical activity). Then, once a group of treatment-resistant patients with similar causes is identified, treatment studies should be conducted to determine which regimens work better.

What do you think the future of epilepsy research and treatment will look like?

That’s a good question. Although we have developed many medications and surgical treatments for epilepsy, the proportion of seizure-free patients has not seemed to change over the years. We need to develop a better understanding of why patients become resistant to medications and how we can better treat them.

Where can readers find more information?

Epilepsy.com, which is run by the Epilepsy Foundation, is a good resource to start and has a wide range of information aimed at different levels of learning, from the basics to advanced topics.

About Dr. Gary Heiman

I received a master’s in Genetic Counseling and subsequently earned a Ph.D. in epidemiology, specializing in genetic epidemiology of neuropsychiatric disorders. My research program mainly focuses on understanding the relationship between neurological and psychiatric disorders, with genetics as a common thread. Individuals with a neurological disorder (e.g., dystonia, Tourette disorder, epilepsy, and Parkinson’s disease), often also have a psychiatric disorder (e.g., depression, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorder).

However, the causes for this relationship remain unclear. While often unrecognized and untreated, having both types of disorders have a profound impact on the individual. Compared with individuals who have only one type (i.e., only a neurologic or psychiatric one), individuals who have both types of disorders report lower quality of life, are at a higher risk for suicide, have a worse disease course, and use more health care resources.

My previous studies of dystonia and epilepsy suggest a shared genetic cause explains some of the reasons for having both types of disorders. As part of a large international study on chronic tic disorders (Tourette and other chronic tic disorders), we are researching the genetics of chronic tic disorders (CTD). Our research has yielded important findings including that over 400 genes may be involved and about 12% of cases are due to a new mutation (i.e., not inherited from either parent). We have also found a few genes that raise the risk for CTD.

About Dr. Brad Kamitaki

Dr. Kamitaki is an assistant professor of neurology. He was born and raised in Honolulu, HI, and graduated from Pomona College, where he majored in Japanese language and literature. He obtained his medical degree from the University of Hawai’i John A. Burns School of Medicine. Dr. Kamitaki completed both his neurology residency and two-year clinical neurophysiology and epilepsy fellowship at Columbia University Medical Center.

Since joining Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in 2018, Dr. Kamitaki has published on several clinical epilepsy and EEG topics, including patient safety in the epilepsy monitoring unit, epilepsy outcomes, quantitative EEG, and health services research. His project aimed at addressing barriers to comprehensive epilepsy care using a mixed-methods, multi-stakeholder approach was recently funded by an early career training grant by the American Epilepsy Society.