As a result of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) this year, there have been several successive waves of infections and deaths attributed to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). It took just a year after the outbreak began for the first vaccines to be developed and rolled out, helping reduce the death toll.

Although severe infections and deaths began to decline dramatically after significant vaccination coverage, immunity began to wane over time. Also, new immune-evading variants emerged, showing resistance to the antibodies elicited by earlier infections and vaccinations.

New research reported in the journal The Lancet examines the temporal association between the two-dose ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Oxford-AstraZeneca) vaccination regimen and the risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 in Scotland vs. Brazil, where the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 was dominant and rare, respectively.

Study: Two-dose ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine protection against COVID-19 hospital admissions and deaths over time: a retrospective, population-based cohort study in Scotland and Brazil. Image Credit: NIAID

Study: Two-dose ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine protection against COVID-19 hospital admissions and deaths over time: a retrospective, population-based cohort study in Scotland and Brazil. Image Credit: NIAID

Background

Several earlier studies have shown short-term effectiveness against COVID-19-related hospitalizations and deaths. This has accompanied large-scale vaccine rollouts in many countries. The ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 adenovirus vector vaccine has been deployed in Scotland and in Brazil, among other countries. This vaccine is preferred by many low- and middle-income countries, being both less expensive and requiring less stringent storage conditions than the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines.

The rising rates of infection and severe COVID-19 have increased despite high levels of vaccine coverage, with decreasing vaccine-induced neutralizing antibody titers over time. This has led to mRNA boosters being offered to provide a higher level of protection to individuals who have received both doses of an mRNA vaccine.

The question remains regarding the differential roles of waning neutralizing antibody titers and the emergence of novel antibody-escape variants. To answer this, the current study looked at Scotland and Brazil, two countries where COVID-19 has taken a high toll on human health and life and where vaccine uptake has been high.

The highest-risk population was prioritized for vaccine uptake in both countries, including frontline health workers and older people. In Scotland, this was rolled back to include only people above the age of 40 due to the (serious but uncommon) adverse effects of clot formation in the brain. In both countries, variants of concern have emerged to dominance, notably the Delta in Scotland and the Gamma in Brazil.

What Did the Study Show?

This was a retrospective population-level cohort study that looked at adult vaccine recipients in both countries who had received both doses of the vaccine. These were compared with unvaccinated people in Scotland and the first monitoring data following a single dose of the vaccine in Brazil.

The data for the Scottish arm of the study came from the EAVE II study, covering almost the whole population, while in Brazil, three datasets were used: COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign (SI-PNI); Acute Respiratory Infection Suspected Cases (e-SUS-Notifica) for contact tracing and suspected cases; Severe Acute Respiratory Infection/Illness (SIVEP-Gripe), for all COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths.

The study covered almost 2 million adults in Scotland and more than 42 million and Brazil. There were disease and confirmed infection peaks in July and September 2021 vs. March and June 2021, respectively.

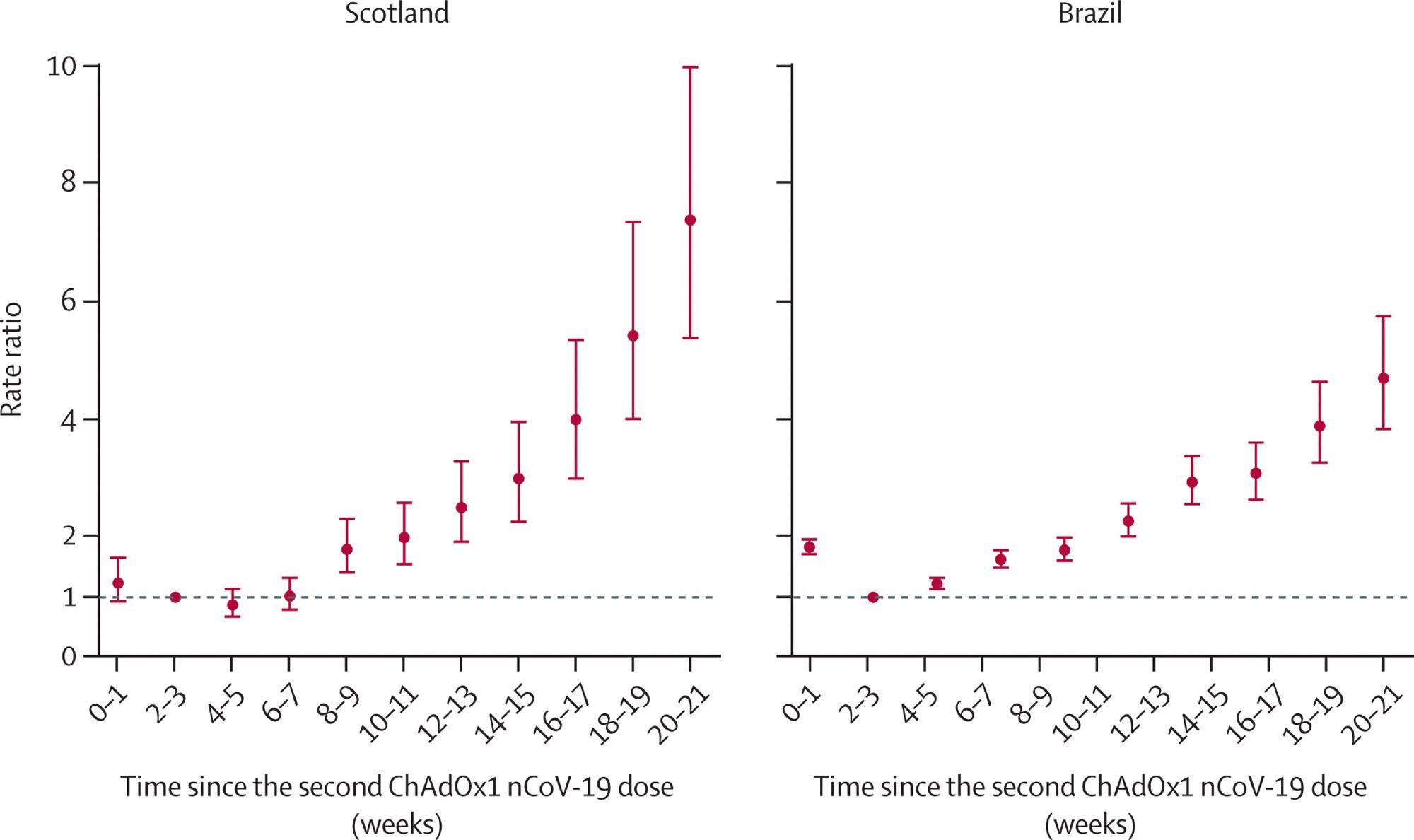

The relative risks for severe disease increased with time in fully vaccinated individuals in both countries. In Scotland, serious infection rates at 2-3 weeks from the second dose of vaccine doubled at 10-11 weeks and tripled at 14-15 weeks. At 18-19 weeks, the rates went up five-fold. Similar patterns were seen in Brazil. This clearly shows waning immunity.

Rate ratios for time since receiving two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and severe COVID-19 (hospital admission or death) in Scotland and Brazil Analyses in Scotland were adjusted for age, sex, deprivation, comorbidities, number of previous tests, interval between doses, and temporal trend. Analyses in Brazil were adjusted for age, sex, deprivation, macroregion of residence, primary reason for vaccination, interval between doses, and temporal trend. Error bars are 95% CIs.

Vaccine effectiveness in the fully vaccinated group remained stable up to 6-7 weeks from the second dose but then went down steadily until 18-19 weeks from the double dose. In Brazil, vaccine effectiveness went until 4-5 weeks and then decreased until the second time point, at 18-19 weeks.

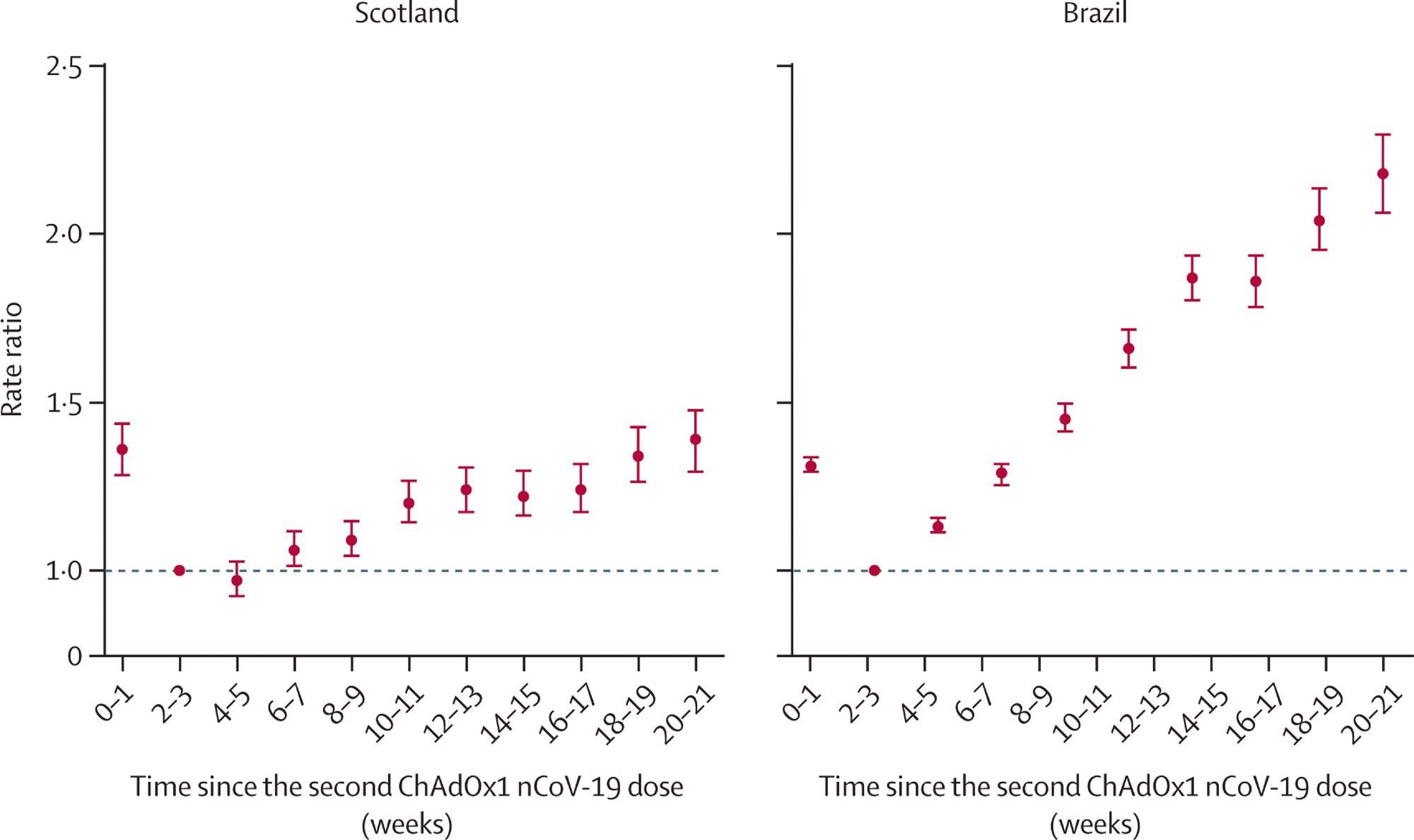

Confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 infections went up in both countries, though the increase in rates was lower than for severe disease. In Scotland, the relative risk was 20% higher at 10-11 weeks than at 2-3 weeks from the second dose and 34% higher at 18-19 weeks. Conversely, in Brazil, it was 66% higher at the first time point but 120% higher at the second.

While Scotland failed to show a clear increase in relative risk for the older (65-79 years) subgroup compared to the younger (18-64 years), this was seen in Brazil. Sensitivity analyses indicate that the real vaccine effectiveness is likely to be higher than these estimates in Brazil but not Scotland.

Rate ratios for time since receiving two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 symptomatic infection in Scotland and Brazil Analyses in Scotland were adjusted for age, sex, deprivation, comorbidities, number of previous tests, interval between doses, and temporal trend. Analyses in Brazil were adjusted for age, sex, deprivation, macroregion of residence, primary reason for vaccination, interval between doses, and temporal trend. Error bars are 95% CIs.

What Are the Implications?

The findings indicate that compared with the risk during the period of greatest protection, at 2-3 weeks from the second vaccine dose, the risk for severe infection increased five-fold at 18-19 weeks in both countries.

Since the dominant variant in these countries was different during this period, there was a definite waning of immunity that is not due to the emergence of the Delta variant or changes in the rate of infections. The short-term effectiveness of this vaccine against severe disease has thus reduced over time.

This mirrors significant attrition of immunity with the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine, from 96% to 84% from 7 days to 6 months following the second dose. In addition, Israeli studies imply a 70% higher risk of severe COVID-19 among those fully vaccinated in January 2021 compared to July 2021.

In the UK, too, the time elapsed since the date of full vaccination with either the BNT162b2 or ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccines was associated with the risk of new infections, and with a fall in anti-spike antibodies over the 3-10 weeks after the second dose.

The study design helps compensate for the inevitable association between the duration since vaccination and the emergence of new variants, especially since most countries prioritized older people for the earliest shots due to their higher risk for severe disease. Moreover, lower infection rates can make identifying decreases in vaccine effectiveness difficult.

Since all participants were fully vaccinated, and those with a prior history of infection were excluded, bias due to the acquisition of natural immunity over time was minimized, as well. This does not exclude the presence of undetected infections, however.

“Our findings suggest that ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine protection against severe COVID-19 wanes within a few months of the second vaccine dose. Consideration should be given to provision of booster doses for those administered ChAdOx1 nCoV-19.”