I am Brian Willett, Professor of Viral Immunology at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research. Our laboratory focuses on the interaction between viruses and the immune system of the host; the immune response to infection, defining the correlates of immunity and developing assays with which the immune response to infection can be measured.

How do viral mutations of COVID-19 occur? Do new viral mutations affect the capabilities of the virus?

One of the key stages in the replication of viruses within a host is copying the genetic material of the virus (the viral genome). This process of genome copying is error-prone, the number of errors varying dependent on the type of virus and the host cells in which the virus grows.

The viral genome carries the coding sequences (genes) for the viral proteins, hence, whenever a mistake is made in the genome copying process this may translate through to an alteration in the sequence of the viral proteins. This in turn may affect the ability of the virus to grow, for example by enabling the virus to bind more tightly to the receptor ACE2, the protein to which the virus binds to enter cells.

Similarly, alterations in the sequence of the surface (Spike) protein may reduce the recognition of the Spike protein by the antibodies made by the host following vaccination or prior infection.

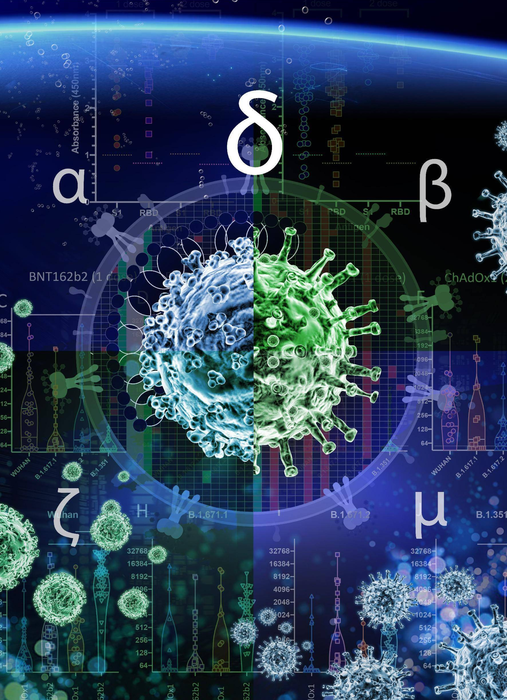

Image Credit: Carl DMaster/Shutterstock.com

COVID-19 vaccines have been proven to be effective in decreasing hospitalization and deaths from infection but new emerging variants could threaten this. Why is it therefore so important to investigate new viral variants of COVID-19?

By measuring the efficiency of the antibody response at reducing infection with the virus (a process known as neutralization), we can estimate the likelihood of existing vaccines providing immunity to either re-infection or disease development.

Using “neutralization” assays, we can monitor the duration of the immune response (how it wanes over time) and the ability of existing antibodies to cross-neutralize emerging variants of the virus.

Can you describe how you carried out your latest research into the COVID-19 delta variant? What did you discover?

In this study, we developed assays with which the level of neutralizing antibodies in serum samples from vaccinated individuals could be measured in our laboratory. By comparing viruses expressing the Spike proteins from several variants of SARS-CoV-2, we found that the Delta variant was less susceptible to neutralization by antibodies from people who have been vaccinated. While antibodies are less powerful against this variant, we know from other studies that the vaccines are largely effective at preventing severe illness and death. However, these findings tell us that the virus is capable of gradually escaping from our immune response over time and are a warning signal that new variants may emerge in the future that could require us to update our vaccines (as we do for influenza every year).

The positive news is that all of the variants tested were neutralized by the sera from the vaccinated individuals, so we would predict that immunity elicited by vaccination with two doses of the existing vaccines would extend to the variants, however, it may not be as effective as it was against the viruses circulating previously (ie the virus of the first wave or the subsequent Alpha variant). Similarly, as antibody responses to coronaviruses wane over time, the duration of immunity be shortened, hence this is why boosters are now being offered in the UK after a 3-month gap rather than the initial, advised 6-month gap.

Should there be ongoing monitoring surrounding the impact viral variants are having on COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness? Do you believe new vaccines will help to tackle new variants of the virus?

By studying the relative levels of neutralization against each of the variants, we can predict how effective vaccination will be at preventing disease. Studies such as this allow us to estimate the relative effectiveness of vaccines against each of the variants and the likely duration of immunity.

Continuous monitoring of the efficiency of neutralization will provide valuable insight into the future trajectory of the pandemic and aid in the development of strategies for selecting the composition of future vaccines.

Image Credit: Murray Robertson

Do you believe that further research needs to be conducted to fully understand the impact viral variants have on COVID-19 immunity? What benefits will this have for virus surveillance?

Of course, continued monitoring of the efficiency of antibodies elicited by vaccination at preventing infection with emerging variants is a key weapon in our armory against COVID-19. The study we have described uses a safe, sensitive, and rapid testing system based on “viral pseudotypes”.

One of the key benefits of this approach is that we can substitute the Spike protein of emerging variants into the assay system with ease, enabling us to compare side-by-side the antibody response to the vaccine strain with each emerging variant, tracking the magnitude of the reduction in neutralization efficiency and duration of immunity. This enables us to predict when boosting may be required, how efficient boosting is at generating a cross-protective immune response, and whether novel vaccine formulations are likely to be required.

What are the next steps for you and your research?

Using the system we have described, we are now investigating the ability of sera from vaccinated or recovered (convalescent) individuals to neutralize merging variants of SARS-CoV-2, the effect of boosting, the degree of cross-neutralization of each variant, and the duration of immunity.

Where can readers find more information?

For further details of the work of researchers at the MRC University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, visit www.cvr.ac.uk. The experiments described in this study are available to view at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010022.

About Professor Brian J. Willett

I am a viral immunologist studying molecular, cellular, and immunological techniques for diagnosing and monitoring viral infections. A graduate of the University of Strathclyde, where I studied Biochemistry and Pharmacology followed by a Ph.D. in Immunology, I joined the Glasgow Veterinary School in 1989, working with Profs. Oswald Jarrett, James Neil and Margaret Hosie on retroviral diseases of cats.

A major focus of the group at the time was feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) as an animal model for AIDS and we made significant advances in retroviral pathogenesis, diagnosis, vaccine development, and viral receptor usage. In our laboratory, we have studied immune responses to diverse viral pathogens of animals and humans, from rabies viruses to feline calicivirus, Rift Valley fever virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, SARS-CoV-2, and morbilliviruses such as measles virus and canine distemper virus.

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, we have established a “serology hub” at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, where we are able to monitor antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 and other emerging viruses using high throughput assay systems, including ELISAs, multiplex chemiluminescence, and viral pseudotype-based neutralization.