This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Background

Easy and unbiased access to COVID-19 testing is the foundation of effective public health response. As a result of the high accuracy of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for the diagnosis of COVID-19, this approach is widely used in Australia.

However, the emergence of the highly transmissible Omicron variant of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), coinciding with a relaxation of lockdown restrictions, has caused an uncontrolled surge in COVID-19 cases in Australia, besieging the PCR testing system. This diagnostic method is also expensive, as the PCR testing system has cost the Australian government $3.7 billion to date.

RATs are an alternative test for COVID-19, which could supplement the current PCR testing system in addition to allowing for the early detection and self-isolation of COVID-19-infected people. Amid concerns that some people will not be able to afford RATs, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approved the use of RATs in November 2021.

About the study

In the present study, the researchers conducted an economic evaluation of whether funding RATs would be cost-effective for the Australian government. In Australia, PCR tests for COVID-19 are free for the public, whereas RATs are available for purchase at supermarkets and pharmacies at the cost of $10-20 per test.

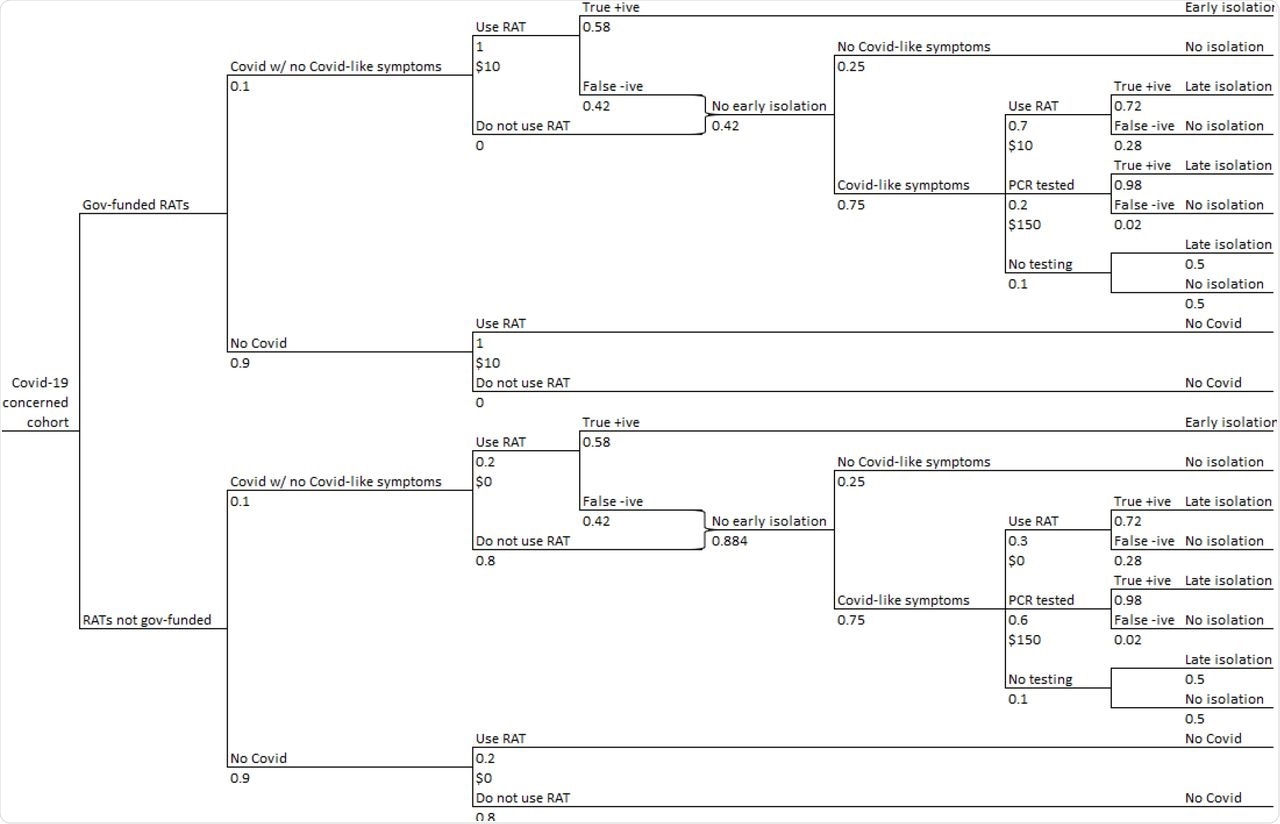

The researchers developed an interactive decision tree model, which described two policies for the Australian government to consider. In contrast, one approach involved government-funded RATs and made them free-for-public-use, the other included individuals purchasing RATs for themselves.

The decision tree represented RAT and PCR testing pathways for a cohort of individuals who would take a RAT test without COVID-19-like symptoms and estimated the likelihood of COVID-19 positive individuals isolating before developing symptoms. Next, the decision tree evaluated the comparative costs of RAT and PCR tests, considering that the PCR testing costs were government-funded and RATs would incur expense only under a policy of government-funded RATs.

Since input parameter values were uncertain, the researchers presented a range of scenarios for analyses. Key input parameters included the prevalence of COVID-19 in individuals using RATs, the unit cost of the tests, and the mean number of tests used per person tested. The model estimations worked on the assumption that 10% of the 'COVID-19 concerned cohort with no COVID-19-like symptoms' will be COVID-19 positive and that 75% of them will eventually develop disease symptoms.

Decision tree structure. Figure presents a decision tree model that describes the testing pathways for a cohort of individuals who do not have COVID-19-like symptoms to estimate the isolation status of the COVID-19 positive members of the cohort. The primary outcome is 'early isolation,' defined as COVID-19 positive individuals who isolate before the development of symptoms. The cohort is defined as individuals who would use RATs if the tests were to be funded by the government. The model estimates individuals' expected testing costs and isolation statuses utilizing a RAT on a single calendar day.

Study findings

The study model estimated that an additional 580 individuals would isolate early under a policy of government-funded RATs at a cost to the government of around $52,000. From these values, for every additional $112 associated with government funding of RATs, one additional individual with COVID-19 and no symptoms would isolate.

Scenario analyses indicated that the incremental cost to the government per additional COVID-19 positive individual isolating with no symptoms would, at most, be a few hundred dollars. These results apply to a cohort of 10,000' COVID-19 concerned individuals' who would use government-funded RATs, assuming 10% prevalence of COVID-19 and 20% of individuals purchasing RATs, even if not government-funded.

According to the study estimates, increasing the prevalence of COVID-19 by 20% and reducing the per-unit cost of RAT by $5 would result in insignificant incremental costs for each early isolated COVID-19 case.

Conclusions

While RAT-based testing allows for the early detection of COVID-19 in infected individuals, in 50-70% of cases, PCR testing detects COVID-19 positives post-infection, thereby leading to unnecessarily longer quarantine times. Although the benefits of early isolation are difficult to quantify, it is an accepted strategy for containing the spread of COVID-19.

According to the study findings, a drop in viral reproduction numbers from 1.5 to 1.2 could reduce daily COVID-19 cases from 20,000 to under 5,000. Furthermore, earlier isolation and controlling COVID-19 transmission could lessen the burden on healthcare facilities and increase the availability of essential workers in Australia, thus economically benefiting businesses.

Taken together, the study presented a range of scenario analyses based on a decision tree model, all of which indicated that even only minor reductions in COVID-19 transmission rates due to early isolation would justify the additional costs associated with a policy of government-funded RATs. In addition, the incremental cost to the Australian government per additional COVID-19-positive individual isolating with no symptoms would only be a few hundred dollars.

Given the potential issues with the supply and distribution of RATs, an implementation strategy targeting a cohort with at least 5% COVID-19 prevalence would be a cost-effective government policy.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources