This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Background

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended an additional booster dose of COVID-19 vaccines for those vaccinated with the primary series post resurgence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Delta variant and waning immunity. To date, there remains limited information on the effectiveness of booster doses in mitigating infection or death in the NH population. Moreover, vaccine trials did not include NH residents; therefore, patient-level observational data is not widely available.

NHs present an environment conducive for VE measurements because of their residential stability, systematic documentation of immunizations, including boosters, and frequent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Additional clinical evidence of booster effectiveness would support plans to increase booster distribution for this highly vulnerable population.

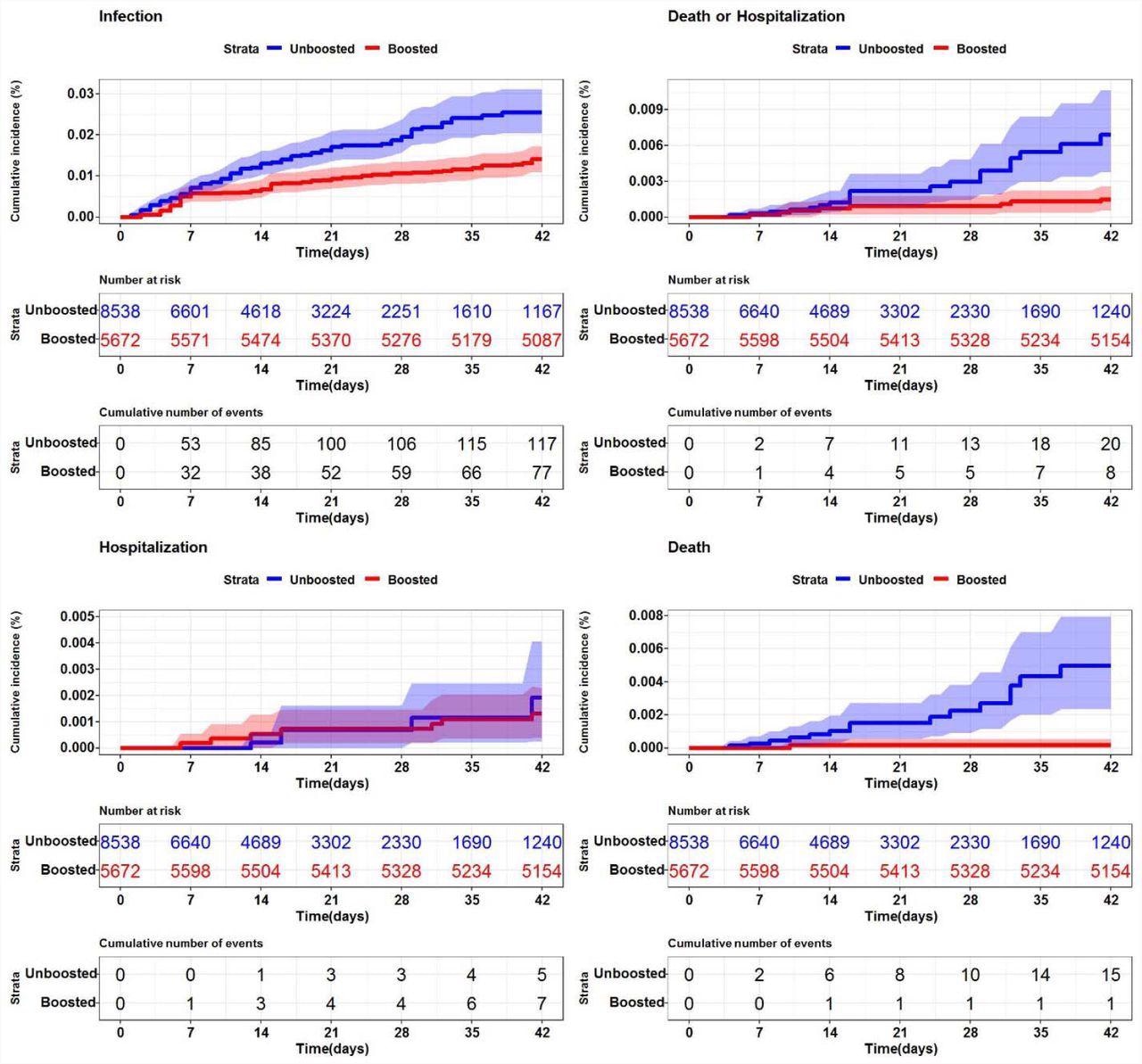

SARS-CoV-2 cumulative incidence in U.S. nursing homes (n=200) by booster status Description. Each graph represents the cumulative incidence for a different SARS-CoV-2 (+) outcome. (Top left - SARS-CoV-2 infection (any positive), Top right - SARS-CoV-2 death or hospitalization, Bottom left - SARS-CoV-2 associated hospitalization, Bottom right - death). The shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals.

About the study

In the present study, researchers used the nested target trial emulation method to evaluate the effectiveness of a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine booster dose at preventing test-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization, or death in two large multi-state NH systems in parallel from September 22, 2021, to November 5, 2021. The Kaplan-Meier estimator assessed the VE at day 42, with both unadjusted and weighted with the inverse probability of treatment.

NH residents who completed a two-dose series of the mRNA vaccine and were eligible for a booster dose were included in the study. A total of 200 NHs and 127 NHs in System 1 and System 2, respectively, were included in the current study. Furthermore, there were 8,538 controls and 5,672 boosted residents, plus 4,100 controls and 2,291 boosted residents in System 1 and System 2, respectively.

In both systems, most NH residents received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, with 4,259 and 1,276 boosted individuals in System 1 and System 2, respectively. The follow-up time contributed was 557,817 days in System 1 and 229,281 in System 2.

There were significant differences in the NH populations. System 1, for example, had primarily older residents over the age of 74 years), fewer black residents, and more female residents. The two treatment populations in both study systems were similar concerning most observed characteristics with standardized mean differences of <0.1.

Study findings

In System 1, booster vaccination reduced SARS-CoV-2 infections by 50.4%, and only one death was reported following boosting versus 15 deaths in non-boosted individuals. In System 2, boosted residents had a 58.2% reduced risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections and two SARS-CoV-2-associated deaths, while there were three deaths in the unboosted population.

Since there were fewer death events in the unboosted population of System 2, it was difficult to estimate confidence interval (CI); therefore, VE was not reported. Additionally, the sample size of System 2 was approximately half of System 1, thereby making direct comparisons of VE inappropriate.

Combined VE for the endpoints of death or hospitalization was 82% in System 1 and 45.8% in System 2. Although the magnitude of events differed, SARS-CoV-2 infection risk was consistently reduced among the boosted population of both systems.

NH residents significantly differed demographically, thus implying that the rates and reasons for acute hospitalization would vary due to differences in availability of hospital care, planning, and health provider practice. However, consistent results across two disparate systems lend credibility to the significance of booster doses for nursing home populations across the United States in general.

The current study method leveraged comparable controls that differed primarily by the timing of vaccination, rather than by indication and exposure risk to circulating strains. The slightly lower VE of 50-54% infection reduction was reported in boosted and unboosted residents and included all post-booster days in the exposure risk calculation during which boost-derived immunity may be incomplete.

Additionally, VE to prevent SARS-CoV-2 mortality in System 1 NH residents was significantly larger and exceeded 90% as compared to previous studies conducted in Israel. These differences could be due to methods used, the health status of the tested population, virus characteristics, or other factors.

Conclusions

The current study evaluated the average VE of an mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine booster in two large multi-state populations of NH residents comparable to trial eligibility criteria. The findings showed that boosted individuals in both the study systems had a much-reduced risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections.

SARS-CoV-2-associated death risk was also reduced in System 1; however, a smaller sample size and event count made inferring death events in System 2 difficult. To conclude, the researchers strongly supported booster dose vaccination for the entire eligible NH population.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

McConeghy, K. W., Bardenheier, B., Huang, A. W., et al. (2022). Effectiveness of a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine booster dose for prevention of infection, hospitalization or death in two nation-wide nursing home systems. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2022.01.25.22269843. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.25.22269843v1.

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

McConeghy, Kevin W., Barbara Bardenheier, Andrew W. Huang, Elizabeth M. White, Richard A. Feifer, Carolyn Blackman, Christopher M. Santostefano, et al. 2022. “Infections, Hospitalizations, and Deaths among US Nursing Home Residents with vs without a SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Booster.” JAMA Network Open 5 (12): e2245417. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.45417. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2799266.