The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) primarily triggers an immune condition that affects multiple organ systems. The intensity of sickness is connected to the individual's primary immunological response and relies on age and comorbidities. The danger of re-infection is determined by the quality of the long-term immune response. However, detailed immunological knowledge is scarce and mostly focuses on antibody reactions.

Study: Durable T-cellular and humoral responses in SARS-CoV-2 hospitalized and community patients. Image Credit: Lightspring/Shutterstock

Immune Responses

The purpose of SARS-CoV-2 mass immunization is to safeguard the community. Long-term memory induced after the first infection is also required for protection against re-infection. The immune response is critical, as it is linked to the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A significant difference has been observed among the two genders regarding immune responses. According to early clinical data, males had a higher risk of severe disease and mortality during acute infection. Reports of immunological variations associated with genders, such as less robust T-cell responses in males and studies of sex differences in immune responses to vaccinations and infection, have backed up these findings. Although the majority of infected people seroconvert, reports of antibody fading and heterogeneity in antibody responses among infected people have raised concerns about long-term protection following infection, particularly in light of the continuing vaccination effort. It's currently unknown which antibody level correlates with protection.

T-cells contribute to antibody synthesis by delaying the B-cell response. However, evidence of re-infection and short-lived immunity against human coronaviruses (HCoV) has sparked fears that protection may be fleeting. With antibody titers declining, cellular immune responses, including B and T cells, will become increasingly important in controlling disease severity.

Although recent investigations have discovered robust cellular immune responses following infection, the duration of these responses is unknown; however, reports of MBCs persisting for more than six months and in the elderly despite a drop in neutralizing antibodies have been made. Cellular responses were identified up to 6 years after SARS in 2003, which is encouraging because they are anticipated to survive longer than antibody responses.

Study Design

During the first pandemic wave in Bergen, Norway (March-June 2020), patients were selected prospectively from patients diagnosed at a centralized outpatient clinic (mildly to moderately unwell) and hospitalized patients (moderate to severe disease - requiring oxygen or ICU treatment).

Fifty-two patients (14 from the hospital and 38 from the community) were followed up with blood samples every two and six months. Blood samples were taken two and six months after diagnosis, and sera were kept at a temperature of 80°C until they were used. In both groups, the median period from diagnosis to follow-up was similar (182 and 188 days), and the majority of patients were male. The two groups had similar age and gender distributions, but the community patients were younger, with a mean age of 52 vs. 60 years. Compared to hospitalized patients, they had significantly fewer comorbidities (37 percent vs. 79 percent) and a lower BMI (median 24.5 vs. 27.1 kg/m2).

Findings

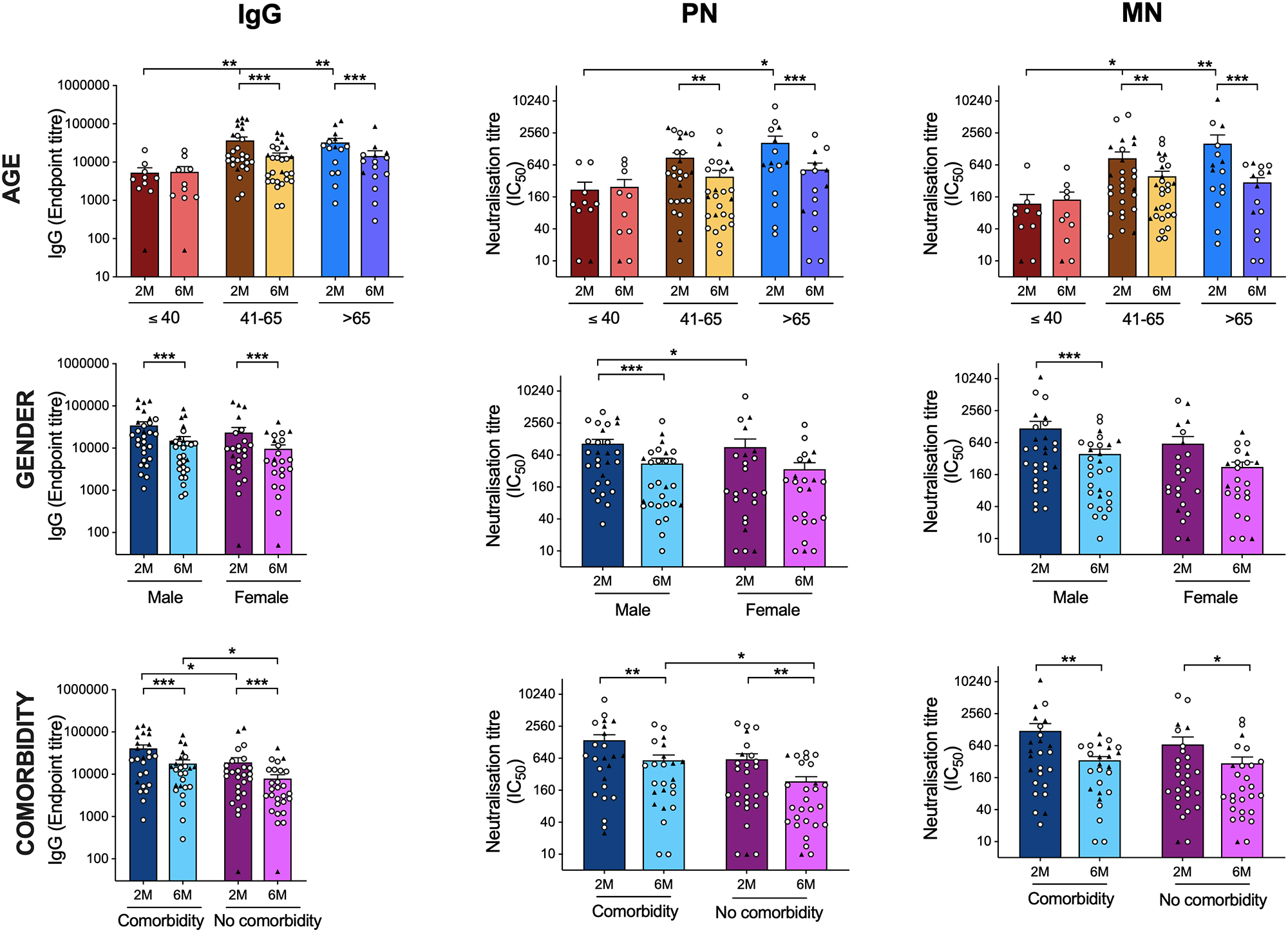

Specific antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 were evaluated using a variety of tests to compare responses at two and six months after infection. The tests were enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), pseudotype neutralization (PN) assay, interferon-γ, and interleukin-2 fluorospot assay, and microneutralization (MN) assays. At two and six months after infection, hospitalized, critically ill patients had considerably more spike-specific IgG than the outpatient ones. In addition, hospitalized patients showed significantly greater MN antibody titers at two months post-infection, with similar PN antibody titers. Also, there were no significant changes at six months. Both groups showed a significant decrease in IgG, IgA, IgM, PN, and MN antibodies between two and six months. Antibody responses were evaluated according to age, gender, and the presence of comorbidities to mirror clinical observations.

SARS CoV-2 antibody responses by age and gender. Comparison of the SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific and neutralization antibody titers according to age (A-C), gender (D-F) and the presence of comorbidities (G-I) is shown, Spike-specific IgG (A, D, G), PN (B, E, H) and MN (C, F, I). Each symbol represents the SARS-CoV-2 antibodies response from one individual with the circle symbol representing community-dwelling patients, and the triangle representing hospitalized patients. The horizontal bars represent the mean T-cell response for each time point ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was determined by the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons tests (* = P<0.05). show less

At two months, the oldest age group with patients above 65 years had the highest levels of IgG, PN, and MN antibodies, which then declined significantly by six months. Patients with known comorbidities had higher levels of spike-specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies PN, but not MN antibodies, at six months. In addition, patients with comorbidities reported greater frequencies of IFN- and IL-2-producing T cells after six months. When stratified by age, the youngest group (less than 40 years old) had the lowest antibody and T-cell responses, all of whom were community patients with less severe illnesses. There were no variations in T cell responses between men and women. In both the hospitalized and community cohorts, gender distribution was equal. However, when compared to the community population, males who were hospitalized had more significant amounts of IFN-producing T cells at six months. This was true only for IL-2 generating T cells that were reactive to spike and internal peptides.

Scope of the Study

Early recruitment of both hospitalized and community patients during the first pandemic wave, along with a comprehensive evaluation of immune responses (including two techniques for neutralizing antibodies to assess possible protection), are the two major benefits of the study.

The researchers discovered long-lasting specific T cells and antibody responses in patients with mild-to-moderate and severe illness. Reports from Denmark have supported these findings in which both moderate and severe cases elicited either a humoral or cellular response.

The results from this study of post-infection T cells binding to more conserved internal viral epitopes give the possibility of cross-reactive T cell protection. This has also been shown after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and the avian H7N9 avian flu outbreak. The lasting antibody and cellular responses identified in this study may protect against re-infection or be increased following vaccination.