Symptoms including fatigue and brain fog have been reported by patients even after the course of a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. The long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the brain, however, are unknown.

Study: Decreased cerebral blood flow in non-hospitalized adults who self-isolated due to COVID-19. Image Credit: DOERS / Shutterstock

Study: Decreased cerebral blood flow in non-hospitalized adults who self-isolated due to COVID-19. Image Credit: DOERS / Shutterstock

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

About the study

In the present study, researchers performed arterial spin labeling (ASL) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to investigate the effect of COVID-19 on the cerebral blood flow (CBF) in non-hospitalized COVID-19-recovered adults.

The team enrolled participants aged between 20 and 75 from May 2020 to September 2021 as part of the NeuroCOVID-19 protocol. The eligible participants were positive for SARS-CoV-2 via a real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (rtRT-PCR) test performed on an oropharyngeal and/or nasopharyngeal swab. The participants were subsequently classified into two groups: (1) the COVID-19 group, including individuals who previously self-isolated following a COVID-19 diagnosis, and (2) the control group, including individuals who tested negative for COVID-19 but reported flu-like symptoms.

The primary outcome of the study included the measurement of ASL-derived CBF. The secondary outcomes were estimated using: (1) a questionnaire regarding flu-like symptoms answered by patients; (2) the cognition and emotion batteries from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) toolbox; and (3) the University of Pennsylvania smell identification test (UPSIT).

Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire in which they indicated the symptoms they were experiencing currently, had experienced previously, or if they had never experienced any flu-like symptoms including sore throat, cough, fever, fatigue, shortness of breath, smell/taste changes, and/or gastrointestinal symptoms.

The cognition battery from the NIH toolbox, a computerized assessment developed to measure the full spectrum of emotional health, generated two age-corrected standard scores of crystallized and fluid cognition, while the emotion battery generated three T-scores representing social satisfaction, negative affect, and well-being. In addition, the UPSIT resulted in scores that evaluated olfactory dysfunction.

As part of sensitivity analyses, the team conducted comparisons between the COVID-19 and the control group. The exploratory analysis assessed whether individuals who belonged to the COVID-19 group and reported fatigue as a current symptom displayed any CBF differences when compared to COVID-19 group individuals who reported previous experience of fatigue or no fatigue at all.

Results

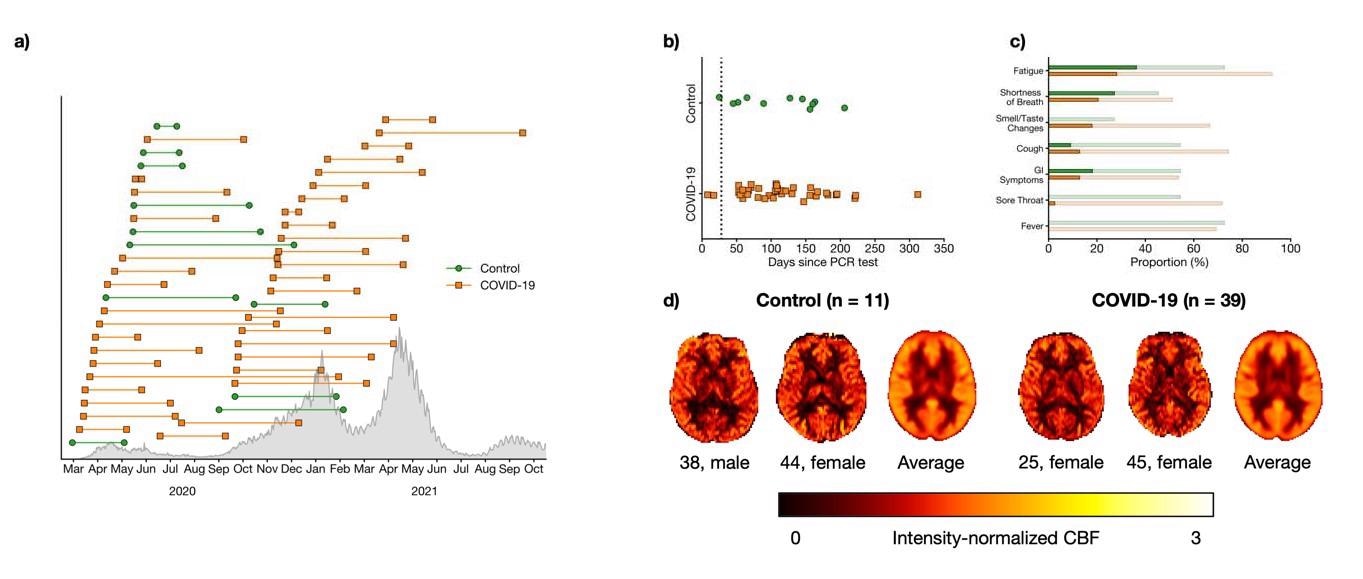

At the time of enrollment, 50 participants, including 39 belonging to the COVID-19 cohort and 11 belonging to the control cohort, were eligible for the study. The team screened COVID-19 group participants 116.5 ± 62.6 days after testing COVID-19 positive.

a) Timing of PCR test (left marker) and assessment (right marker) for COVID-19 (orange squares) participants and controls (green circle). Confirmed cases in Ontario are shown in grey. b) Number of days between PCR test and assessment. The black dotted line indicates 28 days, an established threshold beyond which symptoms can be considered part of the post- COVID-19 condition. c) Proportion of participants who self-reported flu-like symptoms. Faint bars indicate participants whose symptoms had resolved by the time of the assessment while dark bars indicate participants with on-going symptoms. d) Representative and group-averaged CBF maps from both groups.

The study results showed that among the COVID-19 and control participants, 28.2% and 36.4% reported fatigue, and 20.5% and 27.3% had shortness of breath, respectively.

Interestingly, 92.3% of the COVID-19 and 72.7% of the control individuals reported fatigue between the time points of the PCR test and assessment. Moreover, smell/ taste alterations were experienced by more COVID-19 group participants than the control persons. Notably, there were no significant differences between the two groups concerning the cognitive and emotion tests, or the UPSIT scores.

In comparison to the control group, the COVID-19 group displayed significantly reduced CBF in voxel clusters that encompassed the orbitofrontal cortex, thalamus, and the regions such as the caudate, nucleus accumbens, pallidum, and putamen of the basal ganglia. Also, there were no voxel clusters in the COVID-19 group with CBF higher than in the controls.

With partial volume correction, sensitivity analysis showed smaller clusters than those observed in the primary analysis. Again, CBF levels higher than those in the control group were observed in none of the COVID-19 group clusters. On the other hand, the exploratory analyses showed CBF differences among individuals from the COVID-19 group who did and did not report ongoing fatigue. Ongoing fatigue was defined to have increased CBF in the superior occipital and parietal regions with lower CBF levels in the inferior occipital regions (lingual gyrus, occipital fusiform gyrus, intracalcarine cortex, precuneous cortex).

Conclusion

Study results showed a decrease in CBF in those recovering from COVID-19 as compared to controls. The CBF differences with respect to ongoing fatigue as reported by the COVID-19 group suggested the role of CBF in heterogeneous symptoms related to the post-COVID-19 condition. As a whole, the study concluded that post-COVID-19 symptoms are associated with long-term changes in brain physiology and function.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Decreased cerebral blood flow in non-hospitalized adults who self-isolated due to COVID-19, William S.H. Kim, Xiang Ji, Eugenie Roudaia, J. Jean Chen, Asaf Gilboa, Allison B. Sekuler, Fuqiang Gao, Zhongmin Lin, Aravinthan Jegatheesan, Mario Masellis, Maged Goubran, Jennifer S. Rabin, Benjamin Lam, Ivy Cheng, Robert Fowler, Chinthaka Heyn, Sandra E. Black, Simon J. Graham, Bradley J. MacIntosh, medRxiv, 2022.05.04.22274208, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.04.22274208, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.04.22274208v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Kim, William S. H., Xiang Ji, Eugenie Roudaia, J. Jean Chen, Asaf Gilboa, Allison Sekuler, Fuqiang Gao, et al. 2022. “MRI Assessment of Cerebral Blood Flow in Nonhospitalized Adults Who Self‐Isolated due to COVID ‐19.” Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, December. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.28555. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmri.28555.