Monkeypox is a re-emerging zoonotic illness with a case fatality rate of about 10% caused by MPXV, a double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) virus belonging to the Orthopoxvirus genus. Additionally, West and Central Africa are the endemic areas for MPXV.

Several imported human monkeypox cases have been reported recently in countries like the United States (US), the UK, Singapore, and Israel. This phenomenon probably correlates with diminished protection against monkeypox infection offered previously by the smallpox vaccination program in endemic areas.

There may be more imported cases of monkeypox in the future; such instances call for rigorous clinical oversight, including effective infection control measures. Indeed, environmental sampling to recognize contaminated locations potentially posing a threat could guide infection control recommendations.

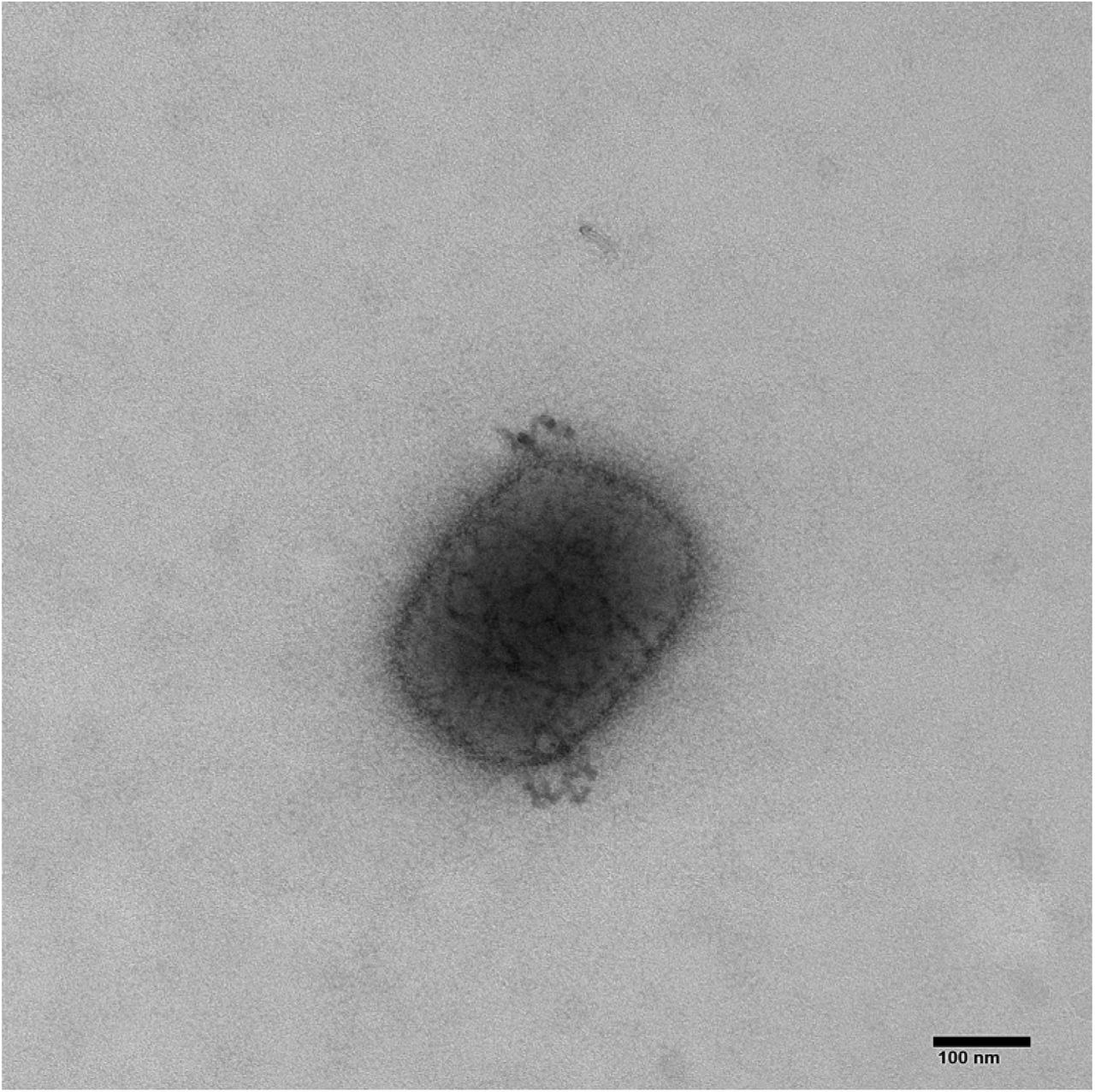

Transmission electron micrograph of Mulberry form pox virion cultured from a towel sampled in the patient’s bedroom. Direction magnificent = x92000.

About the study

The present report details an environmental sampling response in the wake of an imported monkeypox case detected in the UK toward the end of 2019.

In December 2019, a traveler about 40 years returning from Nigeria after a four-week trip to the UK became MPXV-positive. Symptoms started about two weeks before returning with a four-day febrile illness and a persistent extensive pustular rash.

The patient reported no travel to rural regions and had no known interaction with animals, raw foods, or vermin while in Nigeria. Patient samples from three lesions, throat swabs, urine, and blood were examined at the Rare and Imported Pathogens Laboratory in the UK Health Security Agency, Porton, and found MPXV-positive.

Afterward, the team conducted environmental sampling at two adjoining single-room residences occupied by the patient and their sibling. They also analyzed a long-haul commercial bus utilized by the patient to travel nearly 200 miles from the airport to their residence.

Positive samples were identified using both surface and vacuum sampling techniques. The monkeypox diagnosis was validated by pan-orthopox and MPXV-specific real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) testing. The detection of MPXV DNA from different environmental samples was validated using RT-qPCR allied with viral isolation to determine the presence of infection-competent material. Whole-genome sequencing and electron microscopy were applied to positive samples for further confirmation and elucidation.

To sum up, the current paper focused on concurrent research to depict the chance of onward MPXV transmission in settings where the patient spent extended time after returning to the UK and before diagnosis.

Results

The study results indicated that MPXV DNA was detected in several sites throughout the two adjoining single-room residences inhabited by the MPXV-infected person and their sibling. All 21 surface samples from the patient's apartment were MPXV RT-qPCR-positive, with most exhibiting cycle threshold (Ct) values that indicated substantial contamination. Additionally, multiple MPXV-positive samples were found in the sibling's residence, communal areas, and the connecting platform.

Three days after the patient's last visit to these areas, the infectious MPXV was extracted from six samples. These findings verified that contaminated environments might present a risk of onward MPXV transmission.

Four samples chosen for virus isolation could not be proven to contain a viable virus. The Ct values for all four samples were ≥29.9, suggesting an estimate for preferencing samples for virus isolation efforts in future sampling cycles. On the other hand, two samples that yielded viable viruses exhibited Ct values above 29.9, proving that this number was simply an approximation.

Moreover, classic pox-like virions observed using transmission electron microscopy and sequence information from various successful isolations showed that the presently detected MPXV was linked strongly to sequences connected to incidences of recent MPXV importations from Nigeria.

Besides, MPVX DNA could not be detected in any of the samples taken from the bus on which the patient traveled using RT-qPCR. This result suggests no apparent fomite transmission on the bus after the patient's travel. However, the team mentioned that they conducted the sampling around a week after the trip, and the vehicle would have been cleaned by this time. Further, the patient's fellow passengers on the bus and those who boarded subsequently did not report any symptoms of monkeypox.

Conclusions

Overall, the present study verifies the likelihood that infection-competent MPXV could be recovered in environments linked to known positive cases and the need for quick environmental assessments to minimize possible exposure to close contacts and the common public.

Future confirmed cases of monkeypox might benefit from using the techniques used in this investigation for environmental sampling, RT-qPCR recognition, and viral isolation of positive samples. These techniques could assist in the determination of environmental contamination levels, confirming the existence of infection-competent material, and pinpointing areas needing additional cleaning. These adaptations could avert subsequent MPXV cases among close circles or the general public.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Infection-competent monkeypox virus contamination identified in domestic settings following an imported case of monkeypox into the UK; Barry Atkinson, Christopher Burton, Thomas Pottage, Katy-Anne Thompson, Didier Ngabo, Ant Crook, James Pitman, Sian Summers, Kuiama Lewandowski, Jenna Furneaux, Katherine Davies, Tim Brooks, Allan M Bennett, Kevin Richards. medRxiv preprint 2022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.27.22276202, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.06.27.22276202v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Atkinson, Barry, Christopher Burton, Thomas Pottage, Katy-Anne Thompson, Didier Ngabo, Ant Crook, James Pitman, et al. 2022. “Infection-Competent Monkeypox Virus Contamination Identified in Domestic Settings Following an Imported Case of Monkeypox into the\n UK.” Environmental Microbiology 24 (10). https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.16129. https://ami-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1462-2920.16129.