Background

Previous studies have explored the induction of cellular and humoral immunity by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines in the nasal mucosa. However, additional studies are needed to determine whether intramuscular mRNA vaccination can elicit sufficient levels of neutralizing antibodies, as well as B- and T-cells in the nasal tissue.

About the study

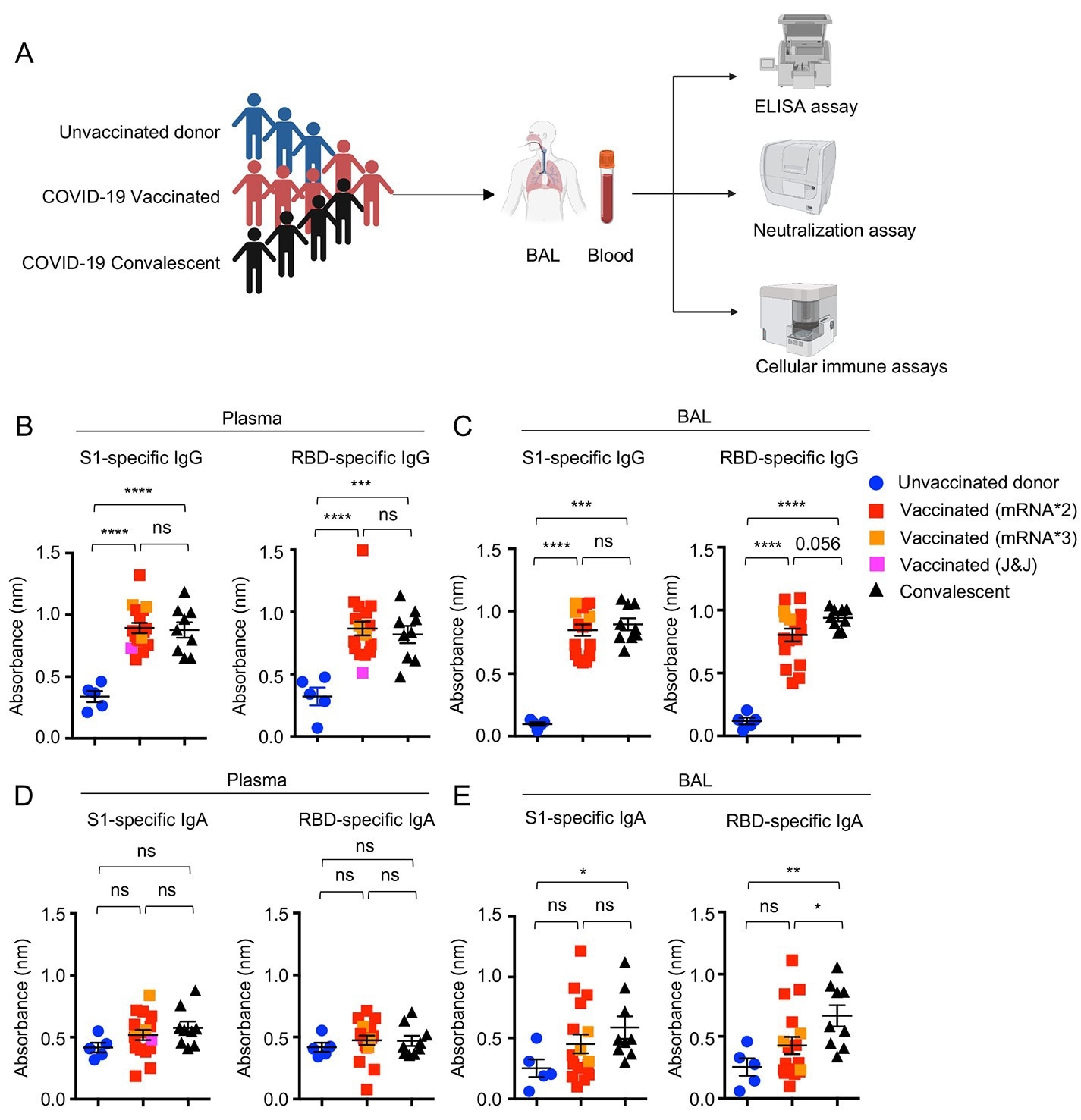

In the present study, researchers compare both cellular and humoral responses against SARS-CoV-2 in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and blood samples obtained from previously hospitalized patients who had recovered from COVID-19 and individuals vaccinated against COVID-19. Of the 19 vaccinated individuals included in the study, most received two doses of an mRNA vaccine, among which three individuals received a third booster dose.

The researchers also utilized the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to assess and compare SARS-CoV-2 spike-1 (S1) and receptor-binding domain (RBD)-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, and IgM levels among both vaccinated and convalescent cohorts, as well as non-SARS-CoV-2 infected unvaccinated individuals.

IgM levels in the BAL and blood were also estimated. The tissue and systemic residing memory B- and T-cell responses elicited after natural infection or mRNA vaccination were also estimated.

The binding antibody response was determined against the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) and spike (S) proteins to determine any unidentified infection. Additionally, the plasma neutralizing antibody activity was estimated against the SARS-CoV-2 D614G strain, as well as the Delta and Omicron BA.1.1 variants.

Study findings

COVID-19 vaccination was found to elicit significant levels of SARS-CoV-2 S and RBD-specific plasma IgG levels that were similar to those produced following severe natural infections. The RBD-specific IgG and S1 levels were also similar in the BAL samples of both convalescent, and COVID-19 vaccinated cohorts.

Systemic and respiratory antibody responses in COVID-19 convalescents and vaccinated individuals. (A) Schematic of recruited cohorts (n=5 for unvaccinated donor, n=19 for vaccinated, and n=10 for COVID-19 hospitalized convalescent) and experimental procedures. Figures were created with BioRender. (B to E), Levels of SARS-CoV-2 S1 or RBD binding IgG (B and C) or IgA (D and E) in plasma and bronchoalveolar (BAL) fluid of unvaccinated donors (n=5), COVID-19 vaccinated (n=17) or convalescents (n=9). One receiving J&J was indicated as pink in the vaccinated group. Three individuals receiving the booster (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) were indicated as orange in the vaccinated group. Enrolled donors’ demographics were provided in Table. S1 or previous publication (19). Data in (B to E) are means ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA and p values were indicated by ns, not significant (P > 0.05), * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), and **** (p < 0.0001).

Systemic and respiratory antibody responses in COVID-19 convalescents and vaccinated individuals. (A) Schematic of recruited cohorts (n=5 for unvaccinated donor, n=19 for vaccinated, and n=10 for COVID-19 hospitalized convalescent) and experimental procedures. Figures were created with BioRender. (B to E), Levels of SARS-CoV-2 S1 or RBD binding IgG (B and C) or IgA (D and E) in plasma and bronchoalveolar (BAL) fluid of unvaccinated donors (n=5), COVID-19 vaccinated (n=17) or convalescents (n=9). One receiving J&J was indicated as pink in the vaccinated group. Three individuals receiving the booster (BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) were indicated as orange in the vaccinated group. Enrolled donors’ demographics were provided in Table. S1 or previous publication (19). Data in (B to E) are means ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA and p values were indicated by ns, not significant (P > 0.05), * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), and **** (p < 0.0001).

A history of severe COVID-19 stimulated significant S1 and RBD-specific IgA levels within the respiratory mucosa, which was not observed in the COVID-19 vaccinated cohort. Despite the lack of IgA identified in the respiratory mucosa among vaccinated samples, moderate but significant IgA levels were detected in the salivary samples of this cohort.

IgM was also detected in the blood of both vaccinated and convalescent individuals. However, only those with a history of COVID-19-related hospitalization exhibited high IgM levels in the BAL samples.

COVID-19 convalescent individuals also exhibited significantly higher concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 S-specific IgA, IgG, and N-specific IgG as compared to vaccinated individuals. However, S-specific IgM levels were not observed in the blood of convalescent individuals.

Significant levels of S-specific IgA were found in the blood and BAL of convalescent individuals; however, these antibodies were not identified in samples obtained from vaccinated individuals. Thus, as compared to natural infection, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination did not produce significant IgA responses.

COVID-19 vaccinated and convalescent individuals exhibited similarly elevated levels of circulating neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. However, as compared to the D614G strain, the Delta and Omicron BA.1.1 variants were associated with two- and 10-fold reductions in neutralization titers (NT50), respectively.

Conclusions

Taken together, both convalescent individuals who were previously hospitalized for COVID-19 and those vaccinated against COVID-19 exhibited similar circulating neutralizing antibody levels. However, previous severe infection with SARS-CoV-2 was found to generate a significantly greater mucosal IgA response than vaccination, particularly against SARS-CoV-2 D614G, Delta, and Omicron variants.

Notably, the Omicron BA.1.1 variant was capable of escaping neutralization by BAL samples obtained from both prior infection and vaccination, thereby confirming the robust immune evasive properties of this variant. Notably, one individual who had received a third vaccine dose exhibited neutralization activity against Omicron, which was low but higher than the threshold, thereby indicating that the booster dose elicited some level of protection against Omicron infection.

The study findings emphasize the need for a mucosal booster COVID-19 vaccine, as this approach may provide a more robust level of protection against re-infection with future SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Journal reference:

- Tang, J., Zeng, C., Cox, T. M., et al. (2022). Respiratory mucosal immunity against SARS-CoV-2 following mRNA vaccination. Science Immunology. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.add4853.