Infections in humans can take place through contact with infected animals or humans. Human-to-human transmission can occur through contact with a skin lesion or large respiratory droplets. The incubation period can vary from 7 to 21 days, with most symptomatic cases being self-limited. The common symptoms include chills, malaise, and fever, followed by the development of a centrifugal rash on the soles of the feet and palms of the hand. Over the next 2 to 4 weeks, the rashes changes from maculopapular to vesicular to pustular to crusting. Moreover, monkeypox infections are often characterized by lymphadenopathy.

However, the current outbreak of monkeypox indicated that the infection could also be asymptomatic with a few asynchronous skin lesions. Most of them appeared in the rectal mucosa, oral mucosa, and genitalia, which are the points of contact concerning sexual settings. This has led to the misdiagnosis of monkeypox, along with delayed treatment. Moreover, reports from Germany and Italy have raised concerns about whether monkeypox is a sexually transmitted disease. Additionally, the increase in the number of monkeypox infections in the endemic parts of Africa and non-endemic parts of the world can be due to a combination of several factors. These factors include no orthopoxvirus cross-protection as a result of smallpox vaccination termination following its eradication in 1980, rapid global travel, and the impact of genetic changes.

A new review published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases aimed to describe the efficacy of vaccinia virus-based smallpox vaccines against the current monkeypox outbreak.

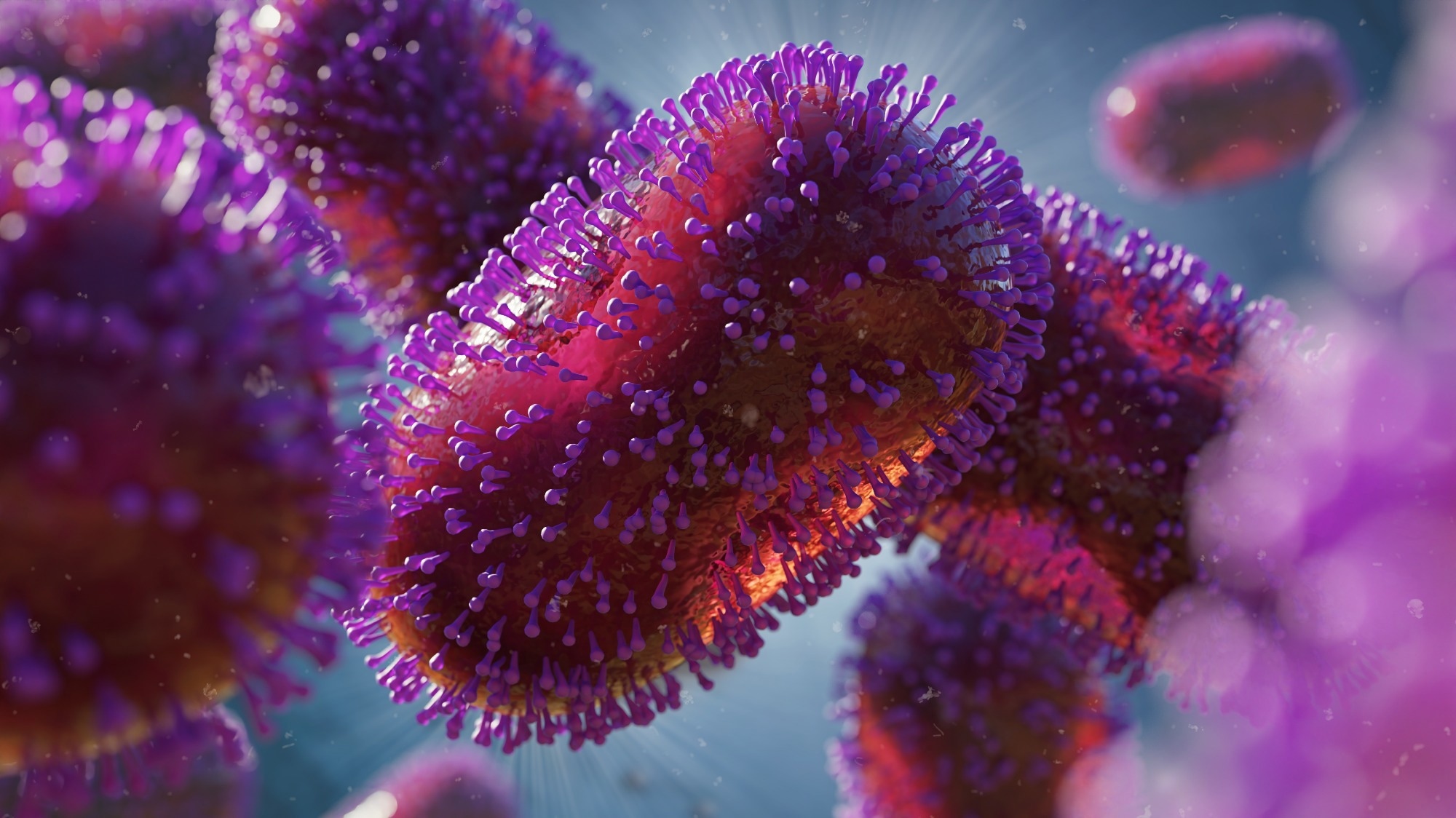

Prevention of monkeypox with vaccines: a rapid review. Image Credit: Dotted Yeti / Shutterstock

Prevention of monkeypox with vaccines: a rapid review. Image Credit: Dotted Yeti / Shutterstock

Impact of vaccination

Previous research has shown that orthopoxviruses can recognize one another and provide protection depending on how closely related they are. There has been speculation that the termination of smallpox vaccination may have led to an increase in monkeypox infections. The immunological cross-reactivity between the two viruses is due to high sequence similarity between orthopoxviruses and a wide breadth of immune responses where antibodies target at least 24 structural and membrane proteins. Previous studies with Dryvax or other first-generation vaccines against smallpox have shown complete protection against monkeypox in cynomolgus macaques, rhesus macaques, and chimpanzees.

Currently, two licensed smallpox vaccines are available in the US, ACAM2000, and JYNNEOS. ACAM2000 is known to be licensed only against smallpox, while JYNNEOS is licensed against both monkeypox and smallpox. ACAM2000 is a second-generation vaccine that has been derived from a single clonal viral isolate obtained from Dryvax. At the same time, JYNNEOS is a third-generation vaccine derived from a non-replicating modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) strain whose 10% of the genome has been deleted. These vaccines can either be used pre-exposure to infection to prevent disease or post-exposure to infection to reduce disease severity. For both cases, second or third-generation vaccines have been found to produce significant results.

However, several side effects have been identified for both first and second-generation vaccines. These include pain and swelling at the site of injection, muscle pain, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, nausea, and headache. Serious side effects included post-vaccinial encephalopathy, eczema vaccinatum, progressive vaccinia, vaccinia, and death. Common side effects of JYNNEOS are reported to be fatigue, nausea, headache, chills, and muscle pain. Both ACAM2000 and JYNNEOS have been found to possess similar immunogenicity, while the adverse events are reported to be lower for the latter. Another third-generation vaccine, LC16m8 has been reported to be derived from the Lister strain used in the first-generation vaccines. It has been licensed in Japan. However, it has not been submitted to the FDA for licensing in the US. The immunogenicity and side effects of the LC16m8 have been observed to be similar to the parental Lister strains.

Non-human primate studies

Non-human primates are better models for human diseases. Studies with all three generations of vaccines in non-human primates showed first-generation vaccines to provide the most robust protection. Most of the animals receiving these vaccines showed no signs of clinical illness, rashes were observed to be limited, and low-level transient viremia was detected. Protection with second-generation vaccines was found to be similar to first-generation vaccines.

Although third-generation vaccines were found to provide strong protection, breakthrough infections were more common. Moreover, the rashes were reported to be more distinct as compared to the first or second-generation vaccines. The antibody titers were also found to be slightly higher in the case of the first or second-generation vaccine compared to the third-generation vaccines.

Human studies

Several previous studies have reported that prior smallpox vaccination reduces the rate of monkeypox attack as well as causes milder symptoms in vaccinated people compared to unvaccinated people. However, a critical factor of the current outbreak involves sexual activity. This could indicate a reduced threshold for infection through sexual activity or a new transmission route. Unfortunately, none of the previous studies have evaluated such scenarios. Therefore, further studies are required to understand the transmission of monkeypox and the effectiveness of vaccines against the current outbreak.

Hypotheses and concerns

The current monkeypox outbreak has led to more than 61,000 confirmed cases across 104 non-endemic countries. Most of these cases have been reported in adult males with a median age of 38. The changing epidemiology of the current outbreak can be due to human behavior, the ability to depart high-risk areas before the onset of symptoms and arrive at international destinations within hours, and the absence of previous smallpox vaccination. One striking feature of the current infection is its rapid transmission which might be due to viral mutation. Two circulating viral strains have been identified in the US that comprise several mutations that suggest longer-term subclinical transmission. In addition, the causative virus of the current outbreak has been reported to belong to the west African clade, which has been previously observed to cause milder disease with lower case-fatality rates.

However, establishing an animal reservoir outside of west or central Africa by the monkeypox virus is currently a significant concern. This reservoir could occur in the prairie dog, rodent, or exotic small pet trade. This could mean that the elimination of the disease would not be possible, and it would continue to risk the global population.

Conclusion

Human monkeypox disease poses a significant risk to the human population. The highest-risk groups include infants, young children, immunocompromised individuals, and pregnant women. Smallpox and monkeypox vaccines and two antivirals are available in the US to combat the disease. However, it is crucial to decide when to use them. The risk, benefit, availability, and utility of the vaccines will impact such decisions.

Additionally, the evolution of the monkeypox genome can increase the risk of transmission, lead to higher virulence, and lower antiviral efficacy of the existing vaccines and drugs. With continuous challenges concerning COVID-19, fragile economies, changing climates, supply chain issues, and threats of war, such risks must be prepared for. Healthcare providers, public health officials, and the general public must be educated regarding the threat of emerging diseases. Efficient tracing, diagnosis, and treatments must be developed for such diseases to ensure global safety.