Studies conducted in urban and non-urban bat colonies have reported the presence of viral nucleic acids and the isolation of multiple viruses from diverse taxonomic families. The Coronaviridae family of viruses was previously detected in this species. However, the CoV shedding patterns in this bat species remain poorly defined, and in general, there is a lack of understanding of CoV ecology in African bats.

Study: Seasonal shedding of coronavirus by straw-colored fruit bats at urban roosts in Africa. Image Credit: Ondrej Prosicky / Shutterstock

Study: Seasonal shedding of coronavirus by straw-colored fruit bats at urban roosts in Africa. Image Credit: Ondrej Prosicky / Shutterstock

About the study

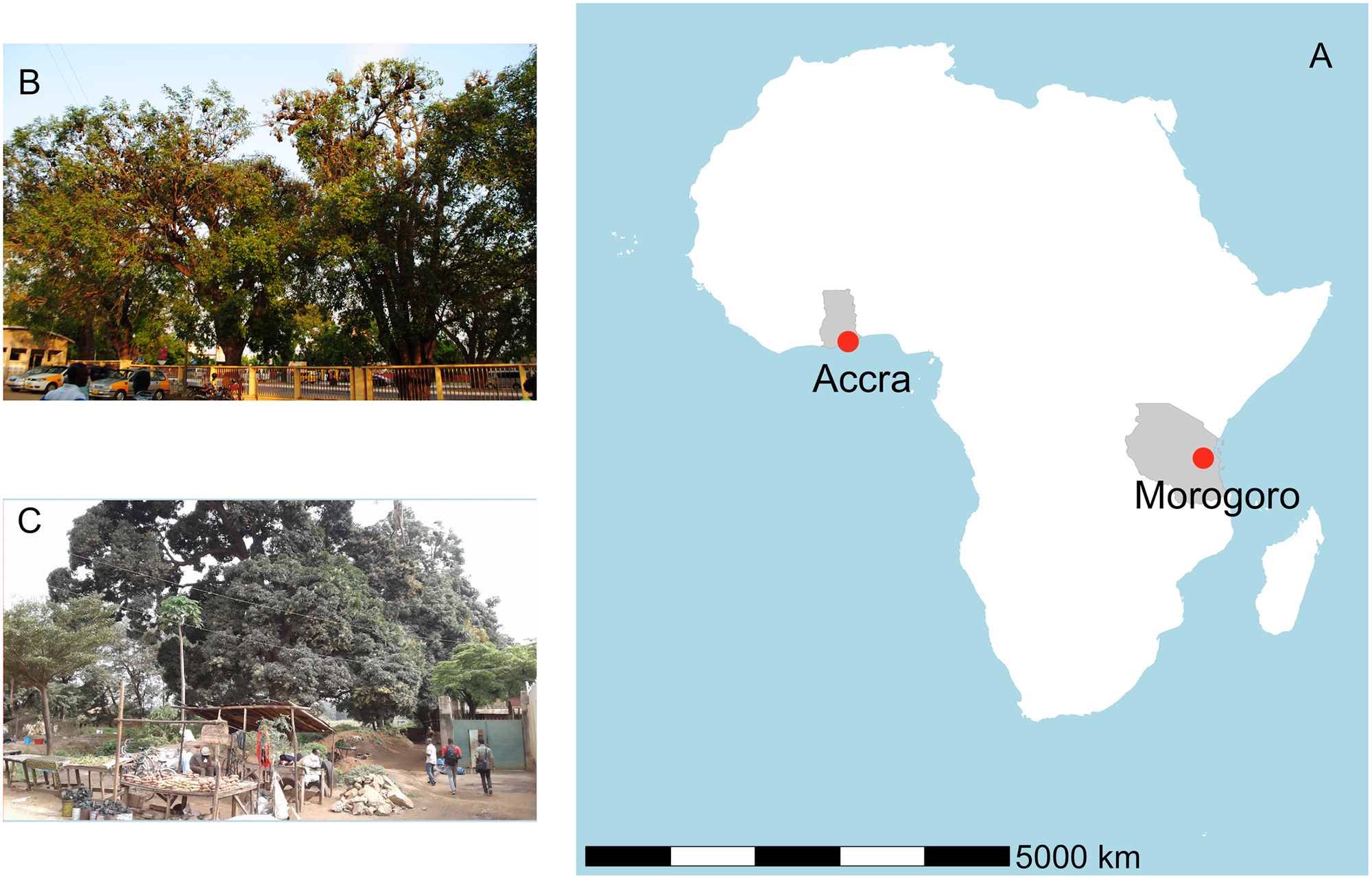

In the present study, researchers investigated the CoV shedding patterns in E. helvum roosts to propose realistic strategies supporting a safer, ethical co-existence of this species with humans. They studied two urban colonies of this bat species, located in Accra, Ghana, and Morogoro, Tanzania. The colony in Accra was studied between March 2017 and February 2018, while the Morogoro roost was studied from August 2017 to July 2018.

The number of bats in each roost was counted monthly. Ninety-seven fecal samples were collected monthly from each roost. RNA from 2,328 fecal samples was extracted, and cDNA libraries were prepared. Two polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays were used to identify known and novel CoVs. Amplified products were cloned and sequenced. A basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) search was performed to compare sequences with existing CoV gene sequences.

The reproductive cycle of bats was estimated based on 1) the authors’ previous data from Accra and Morogoro, 2) prior observations from the two roosts, 3) reported birth pulse and lactation period, 4) synchronized annual birth pulse of this species, and 5) the heterogeneity in the time of pregnancy, estrus and birth pulse. The beginning of the lactation period, the end of the birth pulse, and the start of the weaning period were assumed to be April 15, June 15, and June 16, respectively, in Accra.

In Morogoro, the team assigned December 15 as the lactation period start, February 15 and 16 as the last date of birth pulse, and the beginning of the weaning period. The rest-of-the-year period followed immediately after these time points. The association between CoV shedding and the reproductive cycle was assessed using two logistic models (fixed effects and hierarchical models).

Panel A shows the locations of the roosts in Africa. Panel B shows some of the trees occupied at the 37 Military Hospital in Accra, Ghana and Panel C shows roosting bats at the Kikundi Market in Morogoro, Tanzania. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274490.g001

Findings

The Morogoro bat colony reached peak abundance in February 2018, with 45,000 inhabitants, while the Accra roost peaked in December 2017 with over a million inhabitants. Fourteen fecal samples from Accra and 125 from Morogoro were positive for CoVs. The monthly proportion of positive fecal samples was variable that peaked at 0.24 in Morogoro and 0.04 in Accra.

The proportion of positive samples during lactation and weaning periods was 0 and 0.018 in Accra, and 0.088 and 0.153 in Morogoro, respectively. BLAST analyses revealed that all CoVs identified in the current study exhibited a pairwise sequence identified with Eidolon bat CoV from the Beta-CoV genus.

According to the fixed-effects model, the odds of CoV shedding were 1.24- to 2.65-fold higher than in the rest-of-the-year period. Compared to the lactation period, the weaning period had 1.06- to 3.16-fold higher odds of CoV shedding. The hierarchical model showed increased odds of CoV shedding in the later months of the weaning period relative to the rest-of-the-year period. In addition, the odds of CoV shedding increased during the peak of the weaning period compared to the lactation period.

Conclusions

In summary, the CoVs detected in bat fecal samples from the two roosts had a high sequence identity with Eidolon bat CoV. There was no evidence to suggest that CoVs detected in the two roosts posed a threat to public health unless proven otherwise. The findings support the seasonal shedding pattern of CoVs in both roosts, with a peak shedding during the weaning season.

Overall, the results suggest that resources to prevent human-bat contact should be targeted for use in the weaning seasons and limit human access to roosts and adjacent areas. In addition, the consumption of bats should be discouraged generally, and hunting/selling must be banned seasonally. These recommendations for limiting human-bat exposure apply to all E. helvum roosts across Africa.