Sewer monitoring has emerged as a potentially novel and cost-effective component of public health surveillance. Sewage monitoring involves the collection of pooled samples from sewage systems at the community or institutional levels. Sewers serve as an aggregate for human waste at the community level and a template for community surveillance.

Sewer monitoring can provide valuable insights into what pathogenic viruses, bacteria, and protozoa are prevalent in a community. Regarding public health, wastewater-monitoring programs uncover infections and diseases that may have escaped or are underreported by standard surveillance systems and could potentiate outbreaks.

For instance, wastewater monitoring has been used to detect and track outbreaks of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). During the earlier phases of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, alterations in social constraints were implemented according to community infection levels. There were concerns about whether sewage monitoring data could be used as proof to change social behavior and isolation protocols.

The study

The present study explored whether public perceptions regarding sewage monitoring can be used as a public health surveillance tool – through a survey administered to a sample of individuals across the United States.

The study aimed to evaluate sewer monitoring knowledge, awareness, acceptability, confidentiality, and the variables that affect an individual's awareness of the sewage monitoring agreement.

The findings provided insights into sewer monitoring acceptance and can guide policy formulation about expanding sewer monitoring applications at national and local levels.

Participants were recruited online through Qualtrics XM – a national research panel provider randomly invited to participate in the survey. This survey consisted of three components – questions about knowledge on sewer monitoring and its acceptance; demographic questions, like age, gender identity, geography, race, ethnicity, educational level, and income; and a privacy attitude questionnaire (PAQ)to assess general privacy boundaries.

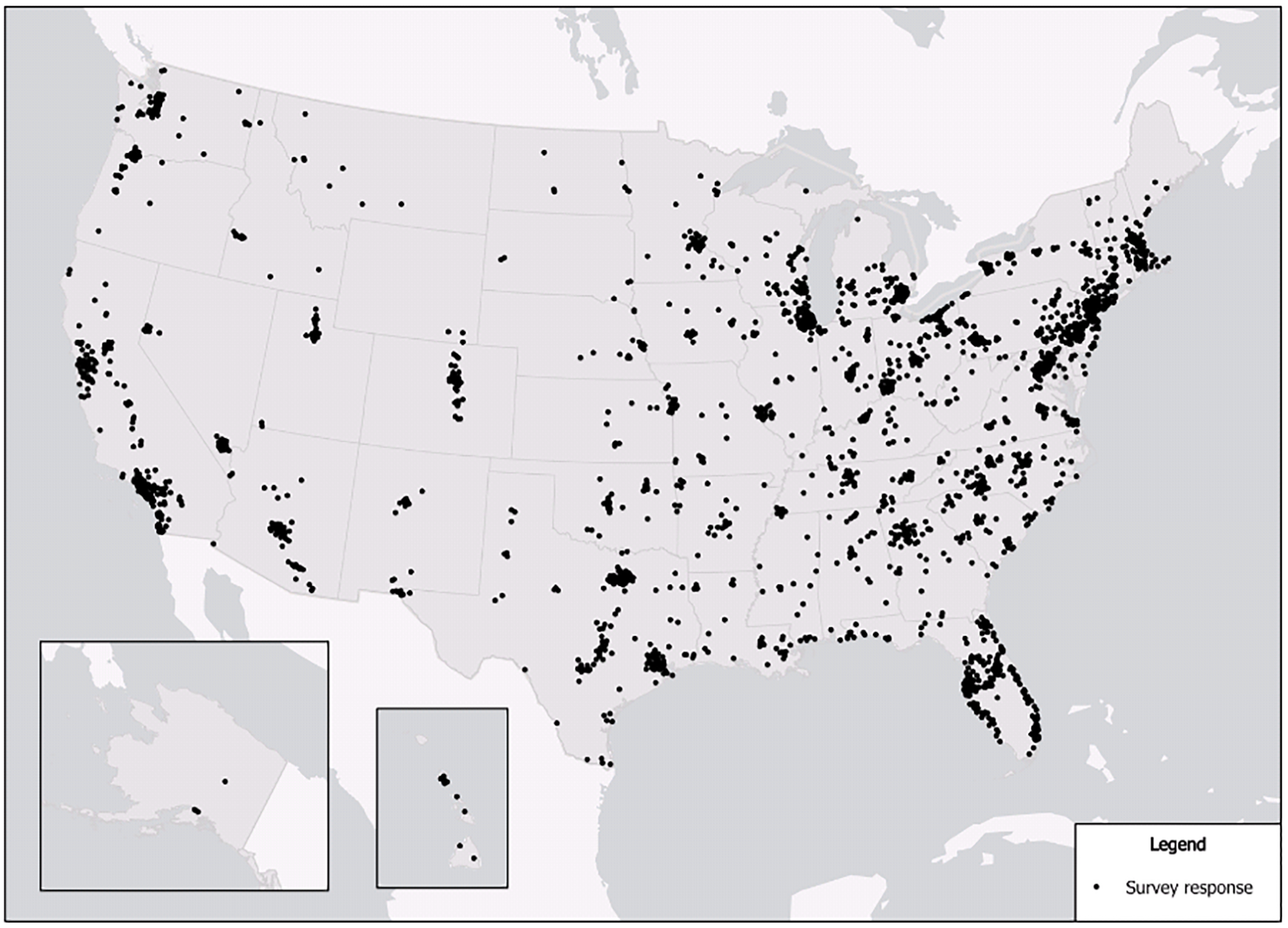

Location of respondents

Location of respondents

The findings

Overall, 3,083 participants answered questionnaires about sewer monitoring as a public health surveillance tool that assessed their knowledge, perceptions, and privacy concerns.

Approximately half of the respondents had no idea whether COVID-19 could be detected in sewage. People across the United States (U.S.) were generally less aware of sewer monitoring than other types of public health surveillance.

Respondents––as measured by the PAQ––showed moderate levels of privacy concerns, with higher levels of concern relating to personal information and lower levels for financial information.

The majority of respondents supported sewer monitoring, particularly for identifying toxins, diseases, and terrorist threats, with a decreasing level of preference in the given sequence. While the support seemed to deteriorate for assessing behaviors and health statuses of the population, such as lifestyle, diet, and mental illness.

There were no significant privacy concerns associated with sewer monitoring across the country. Notably, sampling at the city scale garnered greater support than that at a narrower scale.

Sewer monitoring is an emerging technology, so in areas where public health surveillance is relatively unknown, educational programs may prove to be advantageous in modifying public perceptions. The findings of this survey depict that while knowledge and awareness related to sewer monitoring are low, the U.S. population is specific about what is and is not appropriate for monitoring; public opinion must be considered.

The study had some caveats – the fact that participants were self-selected and the nature of the survey was concealed until the participants met the inclusion requirements. Additionally, survey researchers may have had self-selection bias; the respondents were older, wealthier, better educated, and from the suburbs; residents of rural areas were excluded, and the research was limited to the U.S.

More research is required to evaluate public attitudes toward the use of sewers for worldwide community health monitoring.