*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Background

Immunological memory, which is defined as the ability of the immune system to respond with greater intensity following re-exposure to the same pathogen, is the basic working principle of vaccination. Vaccination continues to be the most effective strategy for preventing the spread of infectious pathogens, as evident through the successful prevention of various diseases caused by viruses like polio and, more recently, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Long-term vaccine-induced immunity is essential for protection against rapidly emerging SARS-CoV-2 mutant strains. The efficacy of this form of immunity can be evaluated by the hosts' circulating, binding, and neutralizing antibodies and spike-specific T-cell and B-cell responses.

Vaccinations are vital for the elderly, as many have comorbidities and are immune compromised. Nevertheless, despite vaccinations, age remains a key risk factor for COVID-19-related hospitalization and death.

This is because the elderly generates suboptimal reactions to their initial immunization. However, the impact of advanced age on COVID-19 booster dose responses remains unexplored.

Current evidence suggests that age significantly impacts the immunological response induced by messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines, particularly after the first vaccine dose. This difference appeared to be reduced with the second booster dose. However, despite the second vaccine dose, T-cell responses in the elderly remain inferior.

The elderly remains a critical target demographic for increasing protective vaccination responses, as they are still disproportionately vulnerable to poor health outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

About the study

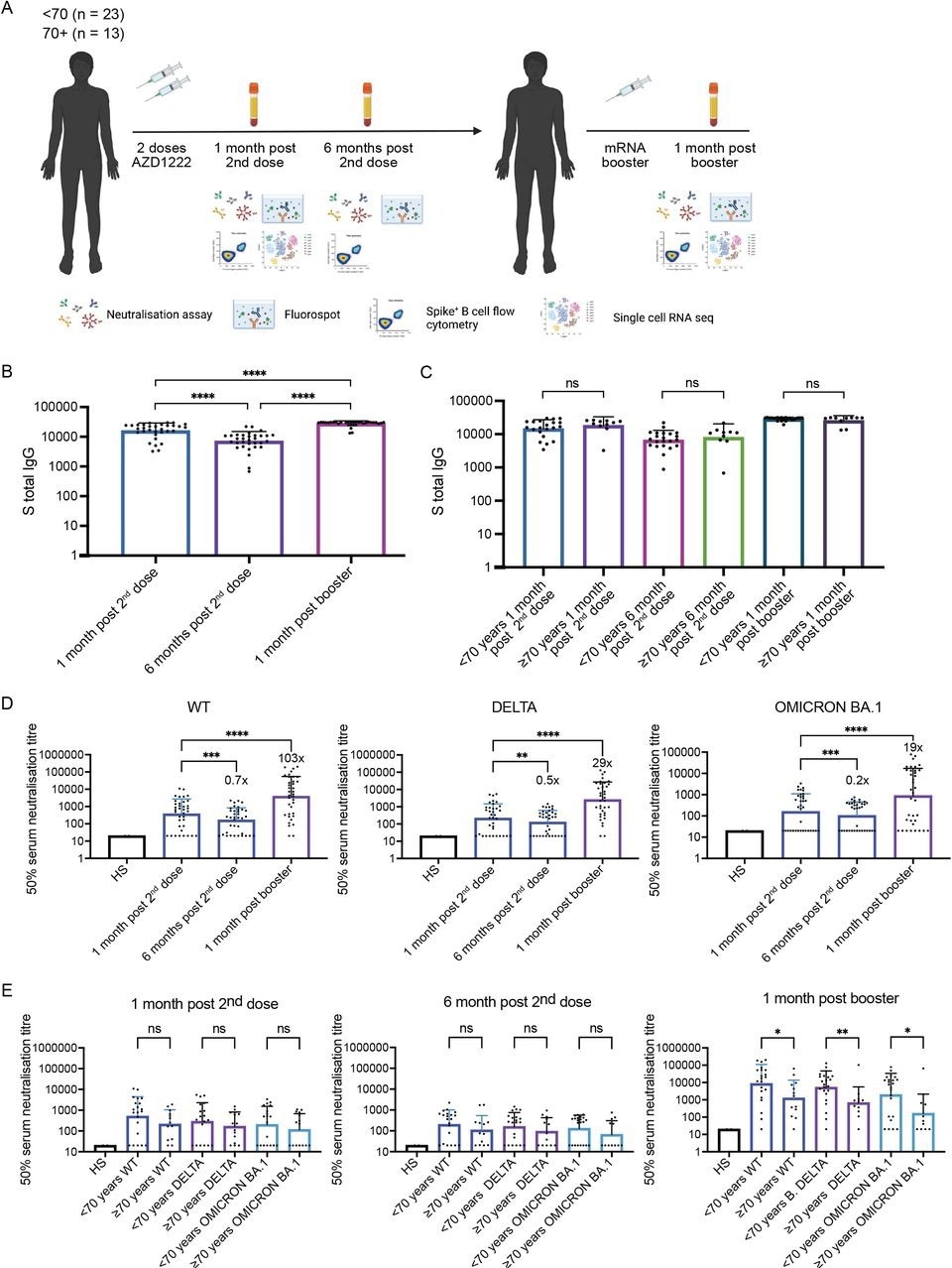

The objective of the current study was to determine the effect of age on responses to the third COVID-19 vaccine dose, as well as determine the mechanistic basis for varied immune responses elicited with increasing age. The investigation focused on those who received two doses of the Covishield-Astrazeneca AZD1222 vaccine and an mRNA booster dose.

One and six months after the second dose, as well as one month after the third booster dose, blood samples were collected. The median age of the participants was 67 years, none of whom were older than 75 years.

The study evaluated the magnitude and durability of the neutralizing antibody and T-cell responses generated by Covishield in 36 participants after the initial two doses. Multiparameter flow cytometry and single-cell RNA sequencing were applied to peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained one month after the second Covishield vaccine dose and one month after the mRNA booster dose. Cell phenotypes, single-cell transcriptomes, and antigen receptor sequences were compared longitudinally across age groups.

Since complementarity-determining regions 3 (CDR3) play an important role in antigen binding, and specificity, the antigen-binding capability of memory B-cells in single-cell B-cell receptor sequencing (scBCRseq) data was determined by analyzing their CDR3 sequences. For this, the public COVID-19 antibody database (Cov-Abdab) was used, as it comprises 10,000 CDR3 sequences experimentally verified for SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies.

Study findings

There were no changes in the neutralizing antibody titers amongst the various age groups at one and six months after the second vaccination dose for three SARS-CoV-2 strains, including the wild-type (WT), Delta, and Omicron variants. As anticipated, neutralizing antibody titers decreased by one log between one and six months after the booster dose.

Neutralizing antibody measurements indicated that the mRNA booster induced a robust response; however, a lower response was depicted in participants aged 70 years or older. On testing motifs enriched in post-vaccination BCRs compared to control infection-naive B-cells, atypical B-cells contained considerable proportions of memory cells expressing SARS-CoV-2 antibody-matched BCRs in individuals above the age of 70 years or older. This effect was more evident after the mRNA booster dose.

Longitudinal neutralising plasma antibody titres against Wu-1 D614G WT, Delta, and Omicron BA.1 variants from AZD1222 vaccinated individuals boosted with an mRNA-based vaccine. (A) Study design - 36 individuals vaccinated with AZD1222 and boosted with an mRNA-based vaccine were recruited. Longitudinal blood draws occurred 1 month post second dose, 6 months post second dose, and 1 month post booster. (B) Total anti-Spike IgG binding antibody responses at 1 month post second dose, 6 months post second dose, and 1 month post booster. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used. **** p < 0.0001. (C) Total anti-Spike IgG binding antibody responses at 1 month post second dose, 6 months post second dose, and 1 month post booster stratified by those below age 70 and those age 70 and above. Mann-Whitney test was used. NS is non-significant. (D) Neutralisation titres (ID50) of sera was measured against Wu-1D614GWT, Delta, and Omicron for each time point. A Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used to determine significance in titres between time points. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. (E) Neutralisation titres (ID50) against against Wu-1 D614G WT, Delta, and Omicron BA.1 stratified by those below age 70 and those age 70 and above. Mann-Whitney test was used. NS is non-significant. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Those over the age of 70 years exhibited reduced B-cell activation after the second (Covishield) vaccination dose. However, the age-associated difference was no longer notable and even reversed after the mRNA booster dose, thus leading to more robust and/or long-lasting transcriptional modifications in B-cells.

There was a comparable rise in the percentage representation of receptor-binding domain (RBD)- and spike-binding non-naive (IgD-) B-cells among lymphocytes one month after the mRNA booster dose as compared to one and six months after the second vaccination (Covishield) dose.

There was a greater proportion of antigen-specific atypical non-naive B-cells in older patients than in younger patients, with an average of 39% of IgD- RBD+ B-cells in those older than 70 years.

The mRNA booster dose stimulated the proliferation of vaccine-specific memory B-cells; however, aging alters B-cell differentiation toward atypical memory B-cells. This contributed to less efficient protective humoral immunity.

The Covishield vaccine conferred long-lasting T-cell immunity, which increased after the mRNA booster dose. However, the booster impact appeared to be subdued in senior patients, especially concerning interleukin (IL)-2 responses.

Even one month after administration of the booster mRNA vaccine doses, continuous transcriptional activation of monocytes, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), and classical dendritic cells (cDCs) were detected, along with the expression of many genes that may enhance T- and B-cell activation.

Myeloid cells, unlike adaptive immune cells, lack conventional immunological memory. Consequently, increased myeloid-cell activation following an mRNA booster dose compared to after two Covishield doses represent a vaccine-intrinsic property.

Limitations

Several limitations were identified in the current study, including a small sample size, peripheral blood sampling for the evaluation of vaccine-induced immune responses, and the lack of clinical data related to COVID-19 protection and severity. As time intervals between vaccine doses vary, such studies become increasingly challenging.

Future research will need to focus on the mechanisms of waning immunity among the elderly, as well as the effects of a fourth vaccine dose and aging.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.