In the early months of the pandemic, black Americans had far higher severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and death rates than their White counterparts. However, gradually, studies evidenced that the COVID-19 racial death disparities shrunk significantly. Intriguingly, this apparent decrease in racial inequality was driven by increasing deaths among white Americans rather than decreasing deaths among black Americans. The fact that Black deaths have decreased does not necessarily mean that factors such as healthcare access and income equality have disappeared.

Initial explanations for COVID-19 racial disparities highlighted the role of static factors, such as historical racial segregation in the US and geography, which are inherently inadequate to explain observed time-varying patterns in racial inequality.

New evidence suggests that this understanding requires a renewed outlook. The partisan divide in pandemic-related policies and beliefs varies over time and across geographies. Also, the state of public healthcare systems, vaccine production, rollout, and uptake are political issues. The study highlights that governments play a central role in combatting pandemics. Thus, it is vital to address the question of racial inequality based on individual behavior and responses, which, in turn, are influenced by political beliefs and ideology.

About the study

In the present study, researchers focused on examining government mandates, containment/suppression policies, and public opinion regarding the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

They acquired weekly data for each US state from Oxford University's COVID-19 government response tracker from May 2021. The team used this data to capture temporal and geographic variation(s) in race-based COVID-19 mortality, total mortality patterns, adherence to policy adoptions, and oscillations in public opinion on both sides of the partisan alley.

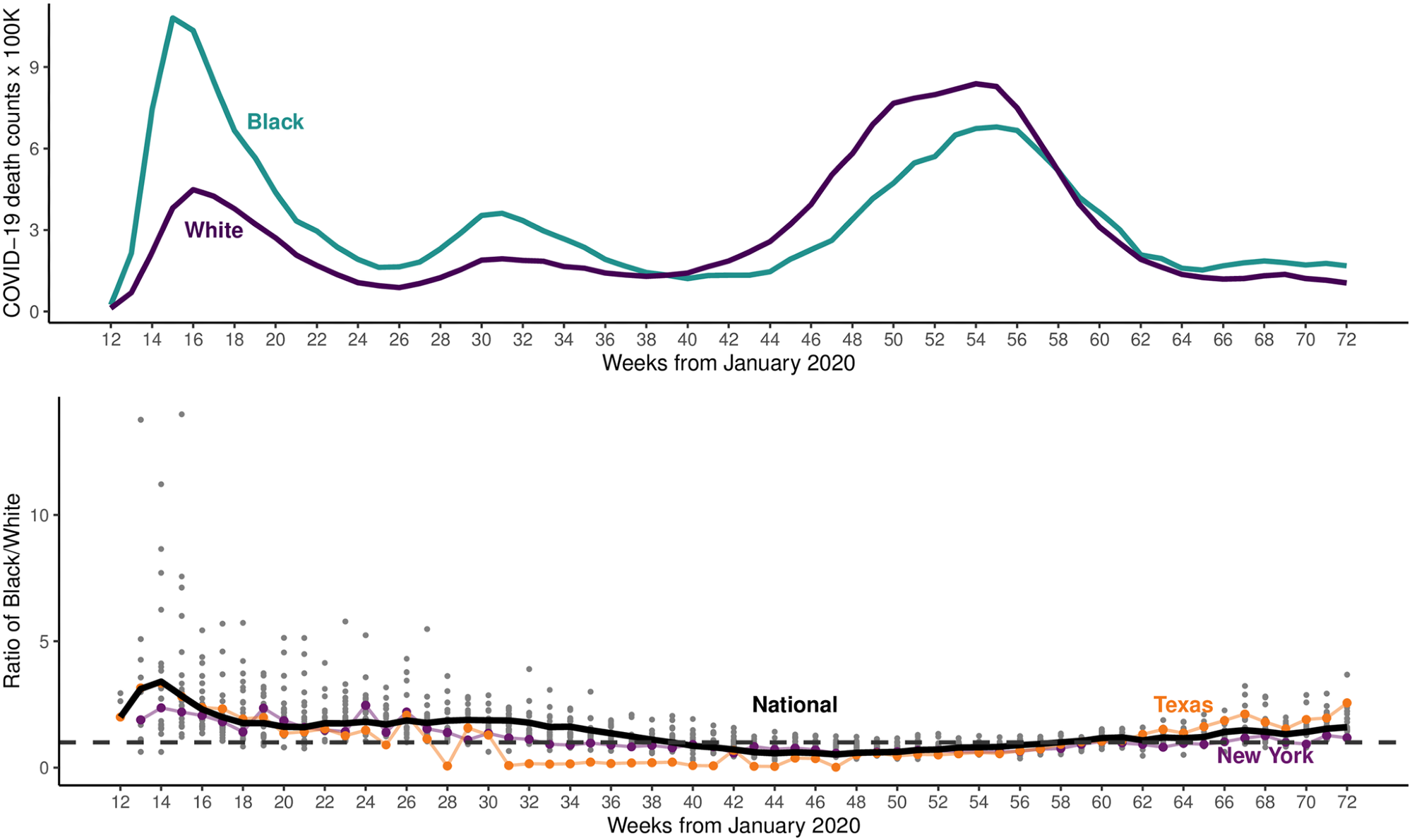

COVID mortality per capita by race (top); black-divided-by-white (bottom) COVID deaths per capita times 100,000.

Study findings

The study findings showed that while mortality varied across races over time, the disparities were higher in Q1 of 2020. Later, it converged over time, driven mainly by increasing mortality in white Americans compared to black. The study analysis also confirmed that since blacks have a comparatively younger general population, black Americans still bear a relatively higher COVID-19-related mortality burden.

The containment and health policies enacted at the state level also varied significantly. Republican governor-led states adopted fewer policies compared to their Democratic counterparts, and that too with significant delays.

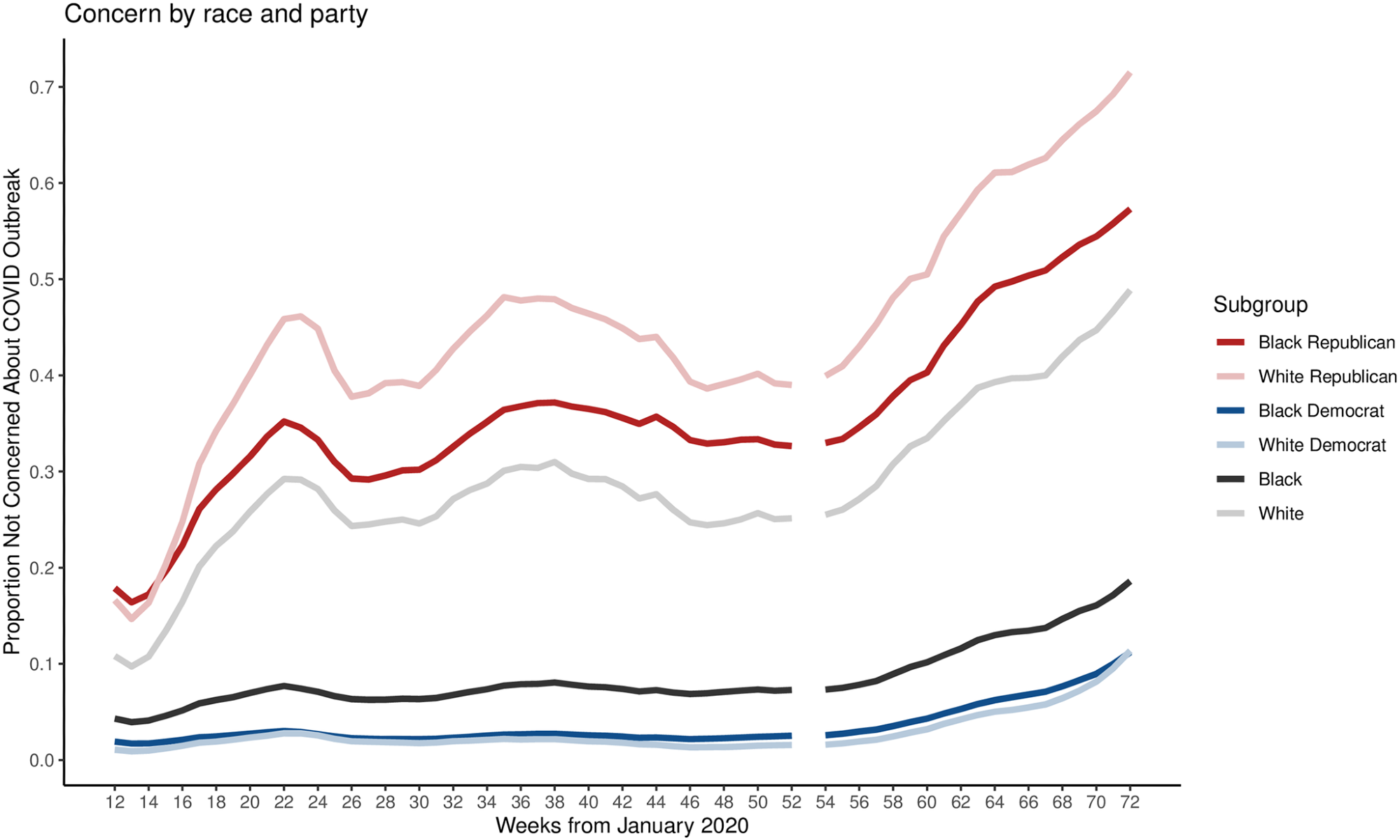

The results also pointed out that the political divide in concern over COVID-19 was a significant causal factor in driving the COVID-19 race-based mortality patterns. As this grew through the pandemic, racial inequality in COVID-19 mortality decreased, but white American deaths increased.

Public concern about local outbreak of COVID-19 by party and race. Differences in the proportion of Americans not concerned with COVID-19 by party (holding race constant) are larger than differences in proportions by race (holding party constant), suggesting partisan disparities in concern dominate racial disparities.

Public concern about local outbreak of COVID-19 by party and race. Differences in the proportion of Americans not concerned with COVID-19 by party (holding race constant) are larger than differences in proportions by race (holding party constant), suggesting partisan disparities in concern dominate racial disparities.

Conclusions

To conclude, the study findings clarified that the shrinking gap in US COVID-19 racial death disparities was due to higher overall deaths rather than a reduction in risk for racial minorities. Initially, infection rates were higher for Black than White Americans, but during the study period, this situation reversed.

Thus, the authors cautioned about interpreting the observed effects as an effect of higher infection rates. Also, the measurement of cases was highly controversial, especially during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, political polarization affected racial inequality in COVID-19 outcomes relatively more through a "race to the bottom" approach.

Future studies should investigate how the partisan divide in the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines will shape emerging patterns of racial inequality in COVID-19 mortality. Also, they should explore how the results of the upcoming US elections might shift policies across states.