Background

The Southeastern regions of the U.S., including Alabama, lag behind the rest of the nation in many health metrics. Several social determinants of health (SDH), such as racial discrimination, govern these poor outcomes, thereby adversely impacting the poor and Blacks in rural areas. Accordingly, about 45% of lab-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related deaths in Alabama were among Black people.

Given that COVID-19 has remained inherently dynamic across time and space, these rural areas bore a higher burden of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the U.S. before vaccines became available.

Despite being the most vulnerable to COVID-19, Blacks, and other marginalized people were not the most likely to be tested for SARS-CoV-2. On the contrary, these populations often struggle to access these facilities due to poor public health infrastructure.

Following the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta strain in July 2021, nearly 11% of Alabama’s five million population underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing. While the case rate for every 1,000 individuals in Alabama was almost triple the rate in metropolitan U.S. cities, SARS-CoV-2 testing percent positivity approached 20% in most rural counties of Alabama in July.

About the study

In the present multicenter study, researchers identified Alabama counties, especially rural ones, in dire need of population-level SARS-CoV-2 testing interventions between October 2020 and March 2021. In their endeavor to optimize the benefits of testing among the marginalized, the researchers collaborated and engaged with local institutions, organizations, and community health workers.

First, the researchers used public data on SARS-CoV-2, including its acquisition risk, disease severity, and practices adopted to mitigate the transmission risk among vulnerable rural communities. County-level SARS-CoV-2 testing percent positivity was modeled according to several covariates associated with the public data.

For example, in October 2020, predictors of the previous 14-day SARS-CoV-2 testing percent positivity and recent county-level estimates for SDH were modeled. Comparatively, in March 2021, average seven-day case positivity predictors were modeled using similar covariates.

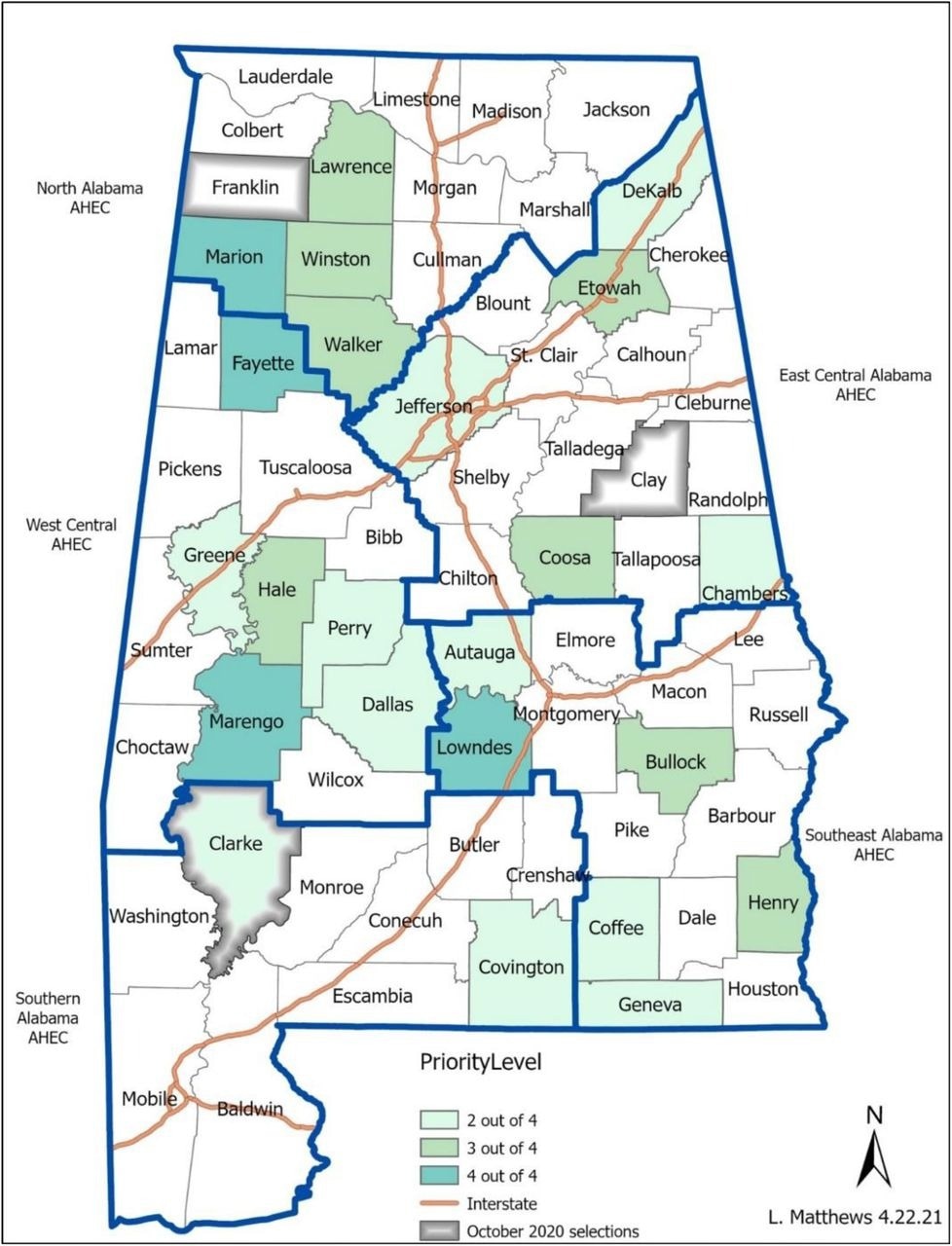

When these models did not differentiate counties for selection, descriptive epidemiological data analyses were performed. After ranking 67 Alabama counties based on four severity criteria, including percent positivity, case fatality, case rates, and the number of testing sites for the study duration, the team selected priority counties that met a minimum of three criteria.

Priority county selections.

Furthermore, the researchers presented epidemiologic data to scientific and community advisory boards. This allowed for certain counties to be prioritized for COVID-19 testing, which, in turn, was predicted to help reduce disease spread, case fatality, and morbidity.

The evolution of the study approach in Alabama, which experienced inconsistent SARS-CoV-2 testing uptake, was also discussed. The lessons learned from the limitations of COVID-19 testing percent positivity in Alabama were also reported.

Study findings

In October 2020, SARS-CoV-2 testing was similar across all Alabama counties, with most populations lacking immunity to the virus. As a result, specific factors driving viral transmission and COVID-19 positivity rates could not be determined.

During the first wave, SARS-CoV-2 testing percent positivity was unrelated to factors modeled by the study. At this time, the researchers also noted more localized COVID-19 outbreaks that were randomly distributed in time and space.

By March 2021, surges in SARS-CoV-2 testing percent positivity were accompanied by preventable hospitalizations and premature deaths at the county level. The periods covered by the study models represent varying features of a dynamic epidemic.

Alabama counties with a higher proportion of Blacks were more likely to exhibit COVID-19 case positivity. Similarly, those living in poorer counties were at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 and had less access to testing. Counties with more smokers were less likely to witness a higher SARS-CoV-2 testing percent positivity.

The adjusted ratio ratios (aRRs) for premature death rates, percent Black residents, preventable hospitalizations, and proportion of smokers associated with average SARS-CoV-2 percent positivity were 1.16, 1, 1.03, and 0.231, with 95% confidence interval (CI), respectively. While the models did not help inform outreach efforts, community partnerships to promote COVID-19 testing strengthened these efforts.

Conclusions

The study findings could help improve future work in other rural settings similar to Alabama. Nevertheless, it was challenging to identify an appropriate metric to identify areas of testing demand during a rapidly evolving pandemic.

Alabama datasets had noise because rapid data availability led to less reliable data. Although real-time, this data was difficult to manage, given the limitations of current data sources and analytic capacities. Conversely, epidemiological data engaged community stakeholders in implementing COVID-19 testing, which is vital to address diseases locally.

Overall, the current study emphasized the importance of a pragmatic approach involving community partnerships and local knowledge to inform testing outreach amid an evolving pandemic.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.