Scientists from the United States have conducted a systematic review to understand whether cattle increase the risk of contracting vector-borne diseases by humans. The review is currently available on the medRxiv* preprint server.

Hematophagous arthropods, including mosquitoes, flies, and ticks, are invertebrates that obtain blood as a food source from vertebrates in various ways. As a result, they can transmit infectious pathogens to humans and livestock, leading to various vector-borne diseases. Some common examples of vector-borne diseases include malaria, Lyme disease, Rift valley fever, Chikungunya, West Nile virus, and other bacterial, protozoal, and viral diseases.

The risk of exposure to vector-borne diseases is comparatively higher for people who handle cattle and livestock at their workplaces, such as farmers, agricultural laborers, and slaughterhouse workers.

In the current systematic review, scientists have explored whether cattle increase or decrease the risk of human exposure to vector-borne diseases.

They screened 470 scientific literature published in peer-reviewed journals between 1999 and 2019 and selected 127 studies for final assessments.

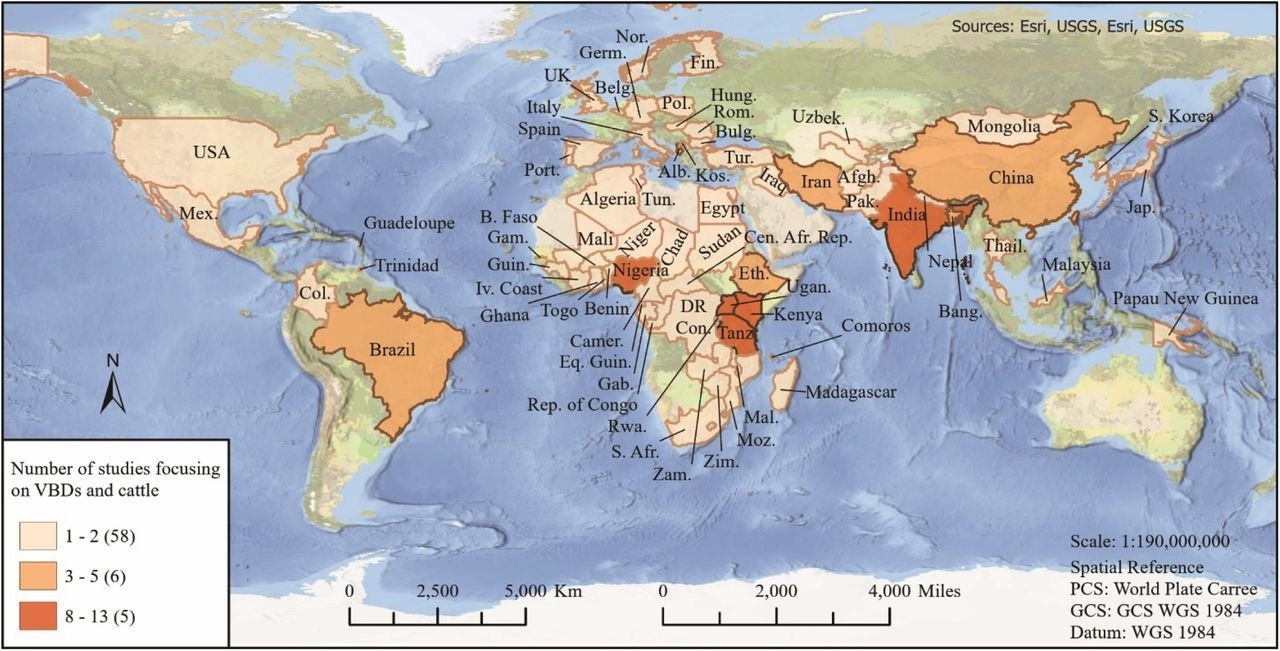

The majority of selected studies were conducted in countries located in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia. The scientists divided these studies into three categories, i.e., beneficial, harmful, or neutral effects of cattle on human exposure to vector-borne diseases.

World map representing countries and number of studies included in this review.

Important observations

The analysis of selected studies indicated that cattle could either increase or decrease the risk of human exposure to vector-borne diseases depending on the type of vector, ecology of pathogens, and livestock management practices. Moreover, the analysis revealed that cattle-mediated risk of exposure is highest for infections transmitted by tsetse flies and ticks, followed by sandflies and mosquitoes.

A total of seven mechanisms were identified in the review by which cattle can impact the risk of human exposure to vector-borne diseases.

Diversion and attraction of vector blood meals

Cattle can have protective effects against vector-borne diseases and can act as an alternative host when disease-carrying vectors prefer to feed on cattle instead of humans. This beneficial effect from cattle is called the zoo-prophylactic effect. Among studies selected in this review, 16 reported this mechanism.

In contrast, cattle can attract vector bites to humans, thereby increasing the risk of human exposure to vector-borne diseases. This effect is called zoo-potentiation. Among studies selected in this review, 18 reported this mechanism.

Environmental modification

Cattle can modify the environment to make it either suitable or unsuitable for specific vectors to survive. Through this mechanism, cattle can impact the risk of human exposure to vector-borne diseases.

As cattle graze, they can modify vegetation, which makes the environment unfavorable for some vectors. In addition, cattle sheds modify the soil to a more alkaline pH. While some vectors prefer alkaline soil for mating, some prefer soil with neutral pH.

This mechanism was found in six selected studies, indicating that cattle may have protective or harmful effects depending on the ecological attributes of vectors.

Incompetent host

Cattle can act as an incompetent reservoir host for specific pathogens, such as the Japanese encephalitis virus. These pathogens cannot survive longer inside cattle bodies; thus, the presence of cattle provides a protective effect against such infections.

Among selected studies, only three reported this mechanism.

Competent host

Cattle can also act as a competent reservoir host for certain pathogens, amplifying their growth and support lifecycle. In some cases, specific pathogens (Example: Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense) can survive inside cattle for a long time without being detected. These pathogens can give rise to significant outbreaks upon the arrival of favorable conditions.

This was the most commonly evaluated mechanism in the review, with a total of 63 selected studies reporting about it.

Direct contact transmission

Consumption of dairy products or meat from infected cattle can increase the risk of infection transmission to humans. The most common examples include Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever, tick-borne encephalitis, Rift Valley Fever, and Alkhurma/Alkhumra hemorrhagic fever.

Direct contact with live or dead infected cattle while handling them in workplaces can also increase the risk of human exposure to vector-borne diseases.

This was the second most commonly observed mechanism, with a total of 28 studies reporting about it.

Interaction between cattle and other animals

The movement of cattle from a disease-endemic region to non-endemic regions and interactions between cattle and other animals during grazing activity can lead to the transmission of vector-borne diseases to new geographical locations. Some common examples include babesiosis and trypanosomiasis.

This mechanism was observed in 26 studies included in the review.

Insecticidal/acaricidal treatment of cattle

Treating cattle with insecticides/acaricides can significantly reduce the proportion of specific vectors (tsetse flies and mosquitoes) in the environment. This is a significant beneficial effect of cattle against vector-borne diseases.

This mechanism was observed in 17 studies included in the review.

Overall, the review demonstrates that cattle can have beneficial or harmful effects on the risk of human exposure to various vector-borne diseases. However, the effect of cattle depends on certain factors, including the type of vector, the nature of pathogen–environment interaction, and livestock management practices.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.