Fungal pathogens threaten global health and food security. Diagnosing and treating fungal infections are complicated, leading to severe illness and death. Besides, cryptic fungal species can also cause infections, and their identification through conventional methods is challenging due to morphological similarities. As such, cryptic fungi's clinical burden and epidemiology are poorly understood. The present study summarized the available information on cryptic fungi.

Study: Know the enemy and know yourself: Addressing cryptic fungal pathogens of humans and beyond. Image Credit: Created with the assistance of DALL·E 3

Study: Know the enemy and know yourself: Addressing cryptic fungal pathogens of humans and beyond. Image Credit: Created with the assistance of DALL·E 3

Diagnosis of fungal pathogens

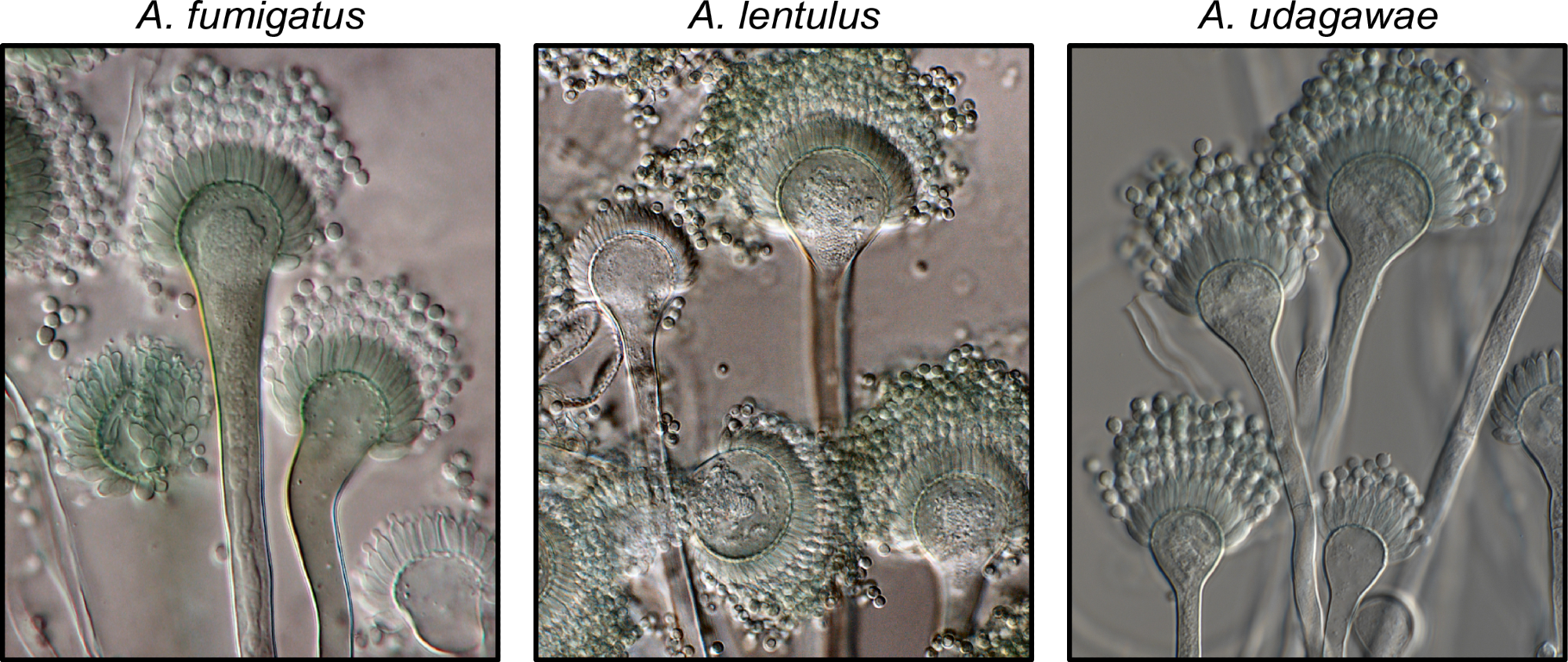

Accurate diagnosis is essential to decrease the burden of fungal infections. Conventional diagnosis methods include microscopy, histopathology, culture, and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometry. These methods have poor specificity, particularly for cryptic species. Nevertheless, molecular typing (phylogenetic analysis) has been more accurate.

However, some loci may not have sufficient information for accurate detection. Aspergillus latus is a cryptic species and allodiploid hybrid that has remained undetected in clinical settings due to the limitations of single-locus typing in a hybrid genome. Extensive phenotyping and genome sequencing have provided robust detection of A. latus. Other approaches, such as phylogenomics, can overcome these limitations.

Although phylogenomics offers high specificity, it requires more time, resources, and expertise. Rapid and affordable diagnosis is critical to lower mortality. Of note, average nucleotide identity is an unexplored alternative. A comparative analysis of various diagnostic methods would determine the most effective method.

Exemplary known and cryptic pathogenic species of Aspergillus. (Left) Aspergillus fumigatus is a well-known and major human fungal pathogen. The cryptic species (Middle) Aspergillus lentulus and (Right) Aspergillus udagawae can also cause human disease but may be difficult to diagnose owing to their morphological similarity to A. fumigatus. Images were kindly provided by Dr. Jos Houbraken. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1011704.g001

Human influence

Humans may unwittingly contribute to the transmission of fungal diseases. For instance, invasive fungal outbreaks have been linked to hospital construction, poor air filtration, and spread through contaminated surfaces. Besides, dietary effects on the abundance of specific fungi in the human mycobiome, human-to-human transmission, and antifungal resistance can also impact the fungal disease.

Examining patient populations and their genetic backgrounds will be critical to understanding how host biology contributes to susceptibility. That is, chronic granulomatous disease patients have a higher risk of infection with A. nidulans. Notably, the associations between cryptic fungal pathogens and specific patient populations are unclear due to the lack of precise diagnosis.

Immune response and disease management

Understanding the interactions of fungal pathogens with the host immune system will provide critical insights into their persistence and clearance mechanisms. Some studies have identified immunological checkpoints for pathogen recognition. Moreover, there is substantial heterogeneity in the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps, i.e., NETosis, across Aspergillus species and strains.

Furthermore, some congenital abnormalities in immune functions may increase the susceptibility to infection in specific populations. For example, individuals with chronic granulomatous disease exhibit higher susceptibility to aspergillosis as they have a lower capacity to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Influence of microbiome and potential future threats

Exploring the human microbiome can help delineate species' impact in cross-species interactions that may prevent or contribute to disease. Mycobiome alterations may contribute to disease severity. Pathogens also impact the mycobiome; that is, lung colonization by A. fumigatus results in microbiome composition being more favorable for fungal growth.

Although studies on the mycobiome have offered vital insights at the genus level, assessing variations at the species or strain level will deepen the understanding of how they influence human health and mycobiome. Cryptic pathogens are often undetected, as identification is possible only at the genus level.

Therefore, species or strain level identification is fundamental, given the phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity. Analysis of non-pathogenic species is also essential, as previously unrecognized species could emerge as pathogens. Exploring pathogens and related non-pathogenic species can provide insights into the emergence of pathogenicity and evolutionary dynamics.

Concluding remarks

Addressing these challenges requires establishing essential infrastructure for accurate diagnosis and dissemination of results. This will facilitate understanding the epidemiology, disease surveillance, and identifying susceptible populations, early outbreaks, and emerging pathogens. Insights from surveillance systems, such as Nextstrain and Microreact, can serve as an inspiration to establish a fungal-specific platform. Overall, integrating microbiome, pathogen, host genetics, and health records data will provide a comprehensive dataset to address the concerns of fungal pathogens.