The researchers retrospectively reviewed all historical milestones in the microbes-based anticancer therapy arena. Further, they summarized the characteristics of intratumoral microbes in various tumors and their effects on cancer development and antitumor immunity.

They also discussed prospective applications of intratumoral microbiota in cancer prognosis and treatment.

Intratumoral microbiota in cancer: Origin, characteristics, and function

Before the 19th century, tumor tissues were considered sterile. In 1885, Doyen, a microbiologist, discovered microorganisms in tumors, giving rise to the concept of intratumoral microbiota.

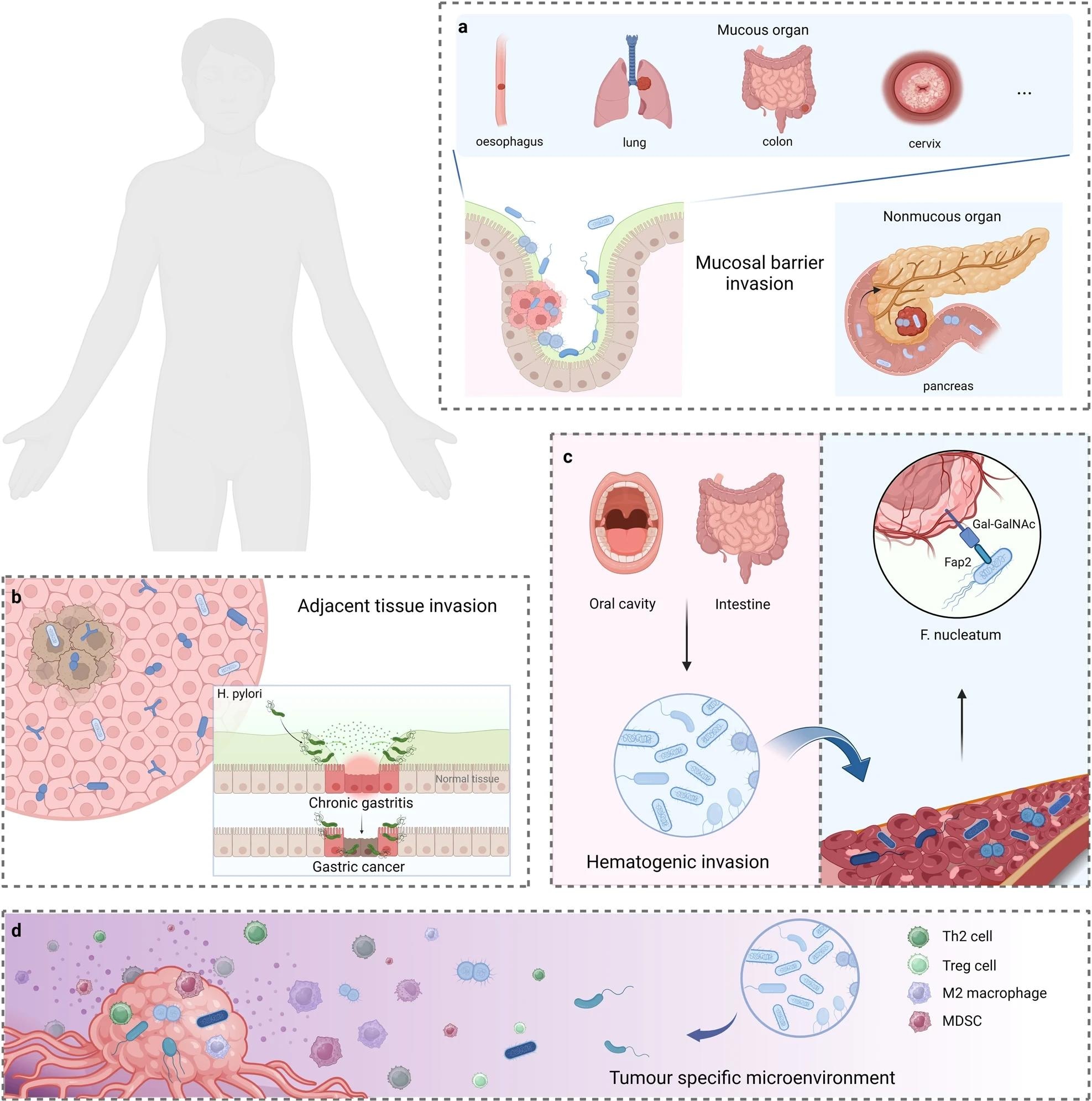

Over time, researchers identified various routes of invasion of microbes in tumors, of which four major ones are mucosal destruction, adjacent tissue migration, and hematogenic invasion. Once they invade the tumor microenvironment (TME), these microbes affect the biological behavior of tumors.

The intratumoral microbiota are highly diverse; accordingly, they vary substantially across different cancer types, subtypes, and stages.

For instance, Modestobacter and Blastomyces are more abundant in lung tumors than adjacent tissues, while Propionibacterium and Enterobacteriaceae are lower. Moreover, lung squamous cell carcinoma microbiota is far more diverse than that of lung adenocarcinoma.

The potential origins of intratumoural microbiota. a Mucosal barrier invasion. Microorganisms may invade the tumor through the damaged mucosa. b Adjacent tissue invasion. the microbiome community between the tumor and adjacent normal tissue shares many similarities. c Hematogenic invasion. microorganisms from the oral cavity, intestine, and other potential locations may be carried to the tumor locations and colonize the tumor through destroyed blood vessels. d Attraction of tumor-specific microenvironment. immunosuppressive, hypoxic, and metabolic nutrient-enriched environments in tumors may enhance microbial colonization. Created with BioRender.com

The potential origins of intratumoural microbiota. a Mucosal barrier invasion. Microorganisms may invade the tumor through the damaged mucosa. b Adjacent tissue invasion. the microbiome community between the tumor and adjacent normal tissue shares many similarities. c Hematogenic invasion. microorganisms from the oral cavity, intestine, and other potential locations may be carried to the tumor locations and colonize the tumor through destroyed blood vessels. d Attraction of tumor-specific microenvironment. immunosuppressive, hypoxic, and metabolic nutrient-enriched environments in tumors may enhance microbial colonization. Created with BioRender.com

Prior research has also revealed the microbiota diversity in liver, colorectal, gastric, breast, pancreatic, oral, head-and-neck, nasopharyngeal, and some reproductive cancers. However, data on the relationships between intratumoral microbiota and other types of cancers remain scarce, warranting further research.

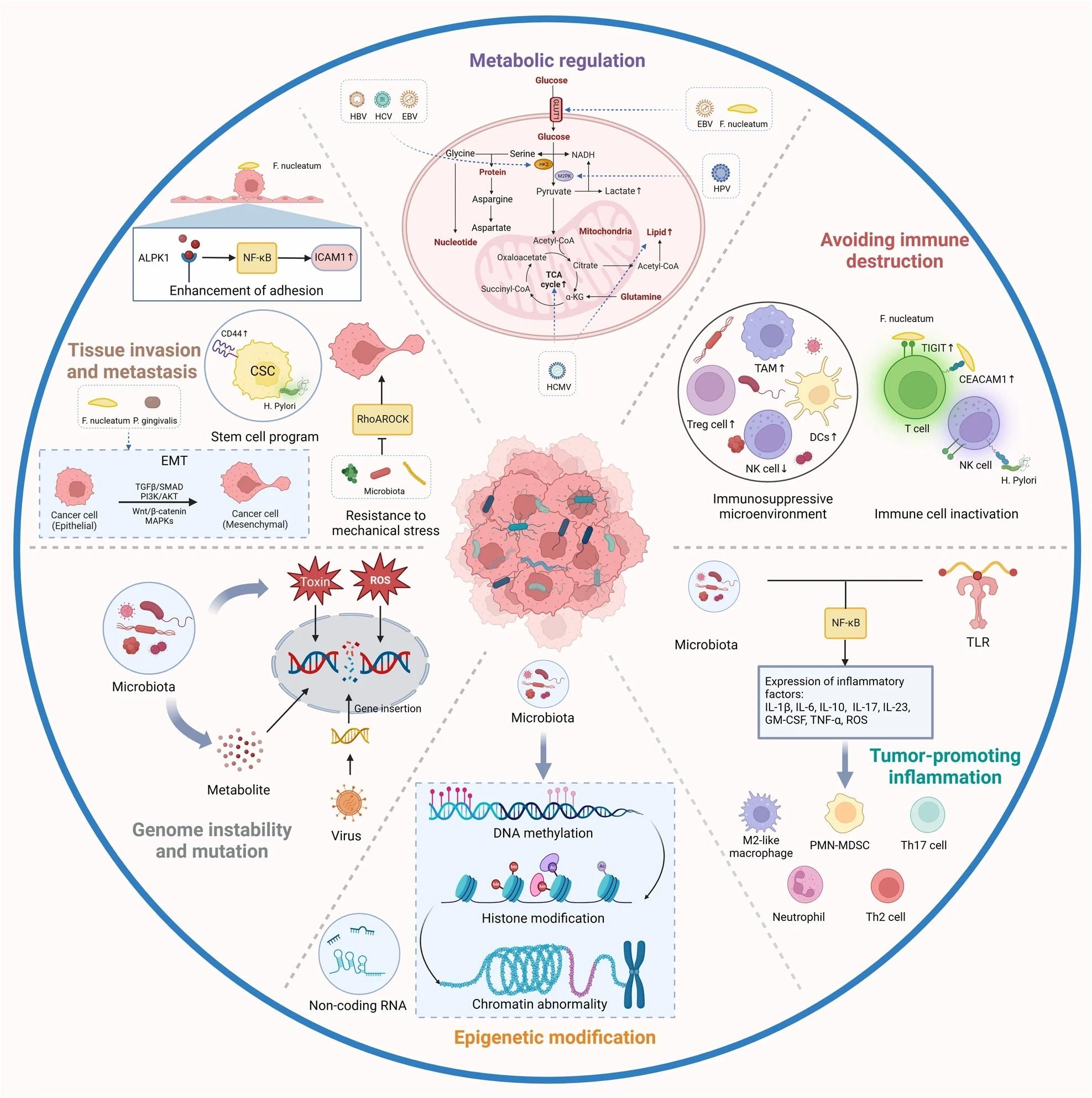

Mechanistic studies have demonstrated that tumor-resident microbes adopt six major mechanisms to influence the initiation and progression of cancer. These are genome instability and mutation, epigenetic modifications, prolonged inflammation, avoidance of immune evasion, metabolism disruption, and activation of metastasis and invasion.

Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) inhibits the DNA repair pathway through the HTLV-1 Tax protein, leading to genome instability. Similarly, bacterial virulence factors (VirFs) directly induce cancer. Breast cancer tissues harbor a carcinogenic enzyme, β-glucuronidase.

Epigenetic modifications such as aberrant DNA methylation are the main pathway for Helicobacter pylori infection to induce gastric adenocarcinoma. Many studies have shown how intratumoral viruses and bacteria directly or indirectly regulate host epigenetic modifications; however, studies should explore their underlying mechanisms.

Inflammation also transforms an immunosuppressive microenvironment to promote tumor progression. Moreover, inflammatory cells at sites of microbial infection produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) to induce DNA damage, thus, contributing to cancer development.

The role of intratumoural microbiota in the development of cancer. The potential effects of the microbiome on the cancer remain elusive. Six major mechanisms have been proposed to explain how the intratumoural microbiota influence the initiation and advancement of cancer, including genome instability and mutation, epigenetic modification, chronic inflammation, immune evasion, metabolic regulation, activation of invasion and metastasis. TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; HK2, hexokinase 2; TCA, tricarboxylic acid. Created with BioRender.com

The role of intratumoural microbiota in the development of cancer. The potential effects of the microbiome on the cancer remain elusive. Six major mechanisms have been proposed to explain how the intratumoural microbiota influence the initiation and advancement of cancer, including genome instability and mutation, epigenetic modification, chronic inflammation, immune evasion, metabolic regulation, activation of invasion and metastasis. TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; HK2, hexokinase 2; TCA, tricarboxylic acid. Created with BioRender.com

Intratumoural microbiota also evades immune responses; for instance, HPV inhibits cytotoxic T and natural killer (NK) cell activation to promote malignancy in human cervical cancer cells.

Similarly, they facilitate metastasis, as shown in a mouse model of colorectal cancer (CRC), where tumor-resident Escherichia coli disrupted the vascular barrier in the gut to promote the recruitment of metastatic cells and the subsequent spread of bacteria to the liver.

However, to date, a deep understanding of the potential effects of all these pathways on cancer remains elusive.

Potential applications of intratumoral microbiota in cancer therapy

With respect to the ability of intratumoral microbiota to predict cancer survival and therapeutic efficacy, research suggests that some species positively correlate with cancer survival, e.g., Fusobacterium species in oral and anal squamous cell carcinomas. Thus, targeting this bacterium with antibiotics may potentially enhance the curative effect in these patients.

While studies have linked high F. nucleatum abundance to poor prognosis of CRC, Alexander et al. found that Granulicatella and Gemella species, it improves disease-free survival (DFS) in patients after CRC resection.

Researchers have also identified other microbiota in association with the prognosis of different cancers. For instance, an abundance of Actinomycetales and Pseudomonadales orders predicted lower DFS in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumors.

Even interventions based on intratumoral microbiota, especially immunotherapy, have shown great potential in anticancer treatment.

Researchers highlighted the use of quadruple antibiotics to prevent and treat H. pylori-derived gastric cancer and antiviral drugs against the hepatitis C virus. Intriguingly, vaccines against herpes papillomavirus and hepatitis B virus can confer protection against many cancers, including that of the cervix in women, head and neck, and liver.

Furthermore, engineered bacteria, e.g., E. coli Nissle 1917, and bacteriophages, e.g., Fusobacterium-targeted phages, have been shown to target harmful microbes within tumors.

Oncolytic viruses also have favorable therapeutic effects against various types of cancer, as observed in both in vivo and in vitro studies. However, given their ability to replicate, they pose safety-related challenges in clinical settings.

Conclusion

The study compiles information and data that may complement future research on intratumoral microbiota-targeted cancer treatments, suggesting the potential for improved cancer treatment options. Given their predictive and prognostic capabilities, intratumoral microbes may also help advance the goal of precision oncology.

In the future, researchers should also aim to develop standardized protocols for studying intratumoral microbes to address the inconsistent findings of previous studies.

More longitudinal prospective studies with large sample sizes are needed to explore the effects of intratumoral microbes on cancer and immune cells and understand the potential for treating tumors by modifying the microbiota.

Such derived critical preclinical evidence and other interdisciplinary approaches might help to draw deep insights into the quantitative relationship between intratumoral microbes and their impact on clinical factors associated with different cancers.

Additionally, exploring these microbial signatures and combination therapies could lead to new targets for clinical intervention in cancer.