Air pollution is one of the leading causes of severe health complications and premature death worldwide. In the United States, air pollution has more detrimental effects on vulnerable populations, including racialized people and socioeconomically deprived people.

On days with poor air quality, the US health authorities issue alerts advising people to stay indoors and limit outdoor air exposure for protection. Around 15 – 20% of Americans currently protect themselves from poor air quality by limiting their outdoor activities.

Recent changes in climate conditions have significantly affected air quality globally. Poor air quality not only negatively affects human health but also increases healthcare costs. Climate policy can offer significant and equity-improving health benefits by improving air quality. Increasing adaptation to poor air quality can also prevent health complications.

In this study, scientists have explored the impact of climate change on the rate of air quality alerts in the US over this century. They have also examined which populations are most affected by poor air quality and how climate policies can improve adaptation to reduce health risks.

Important observations

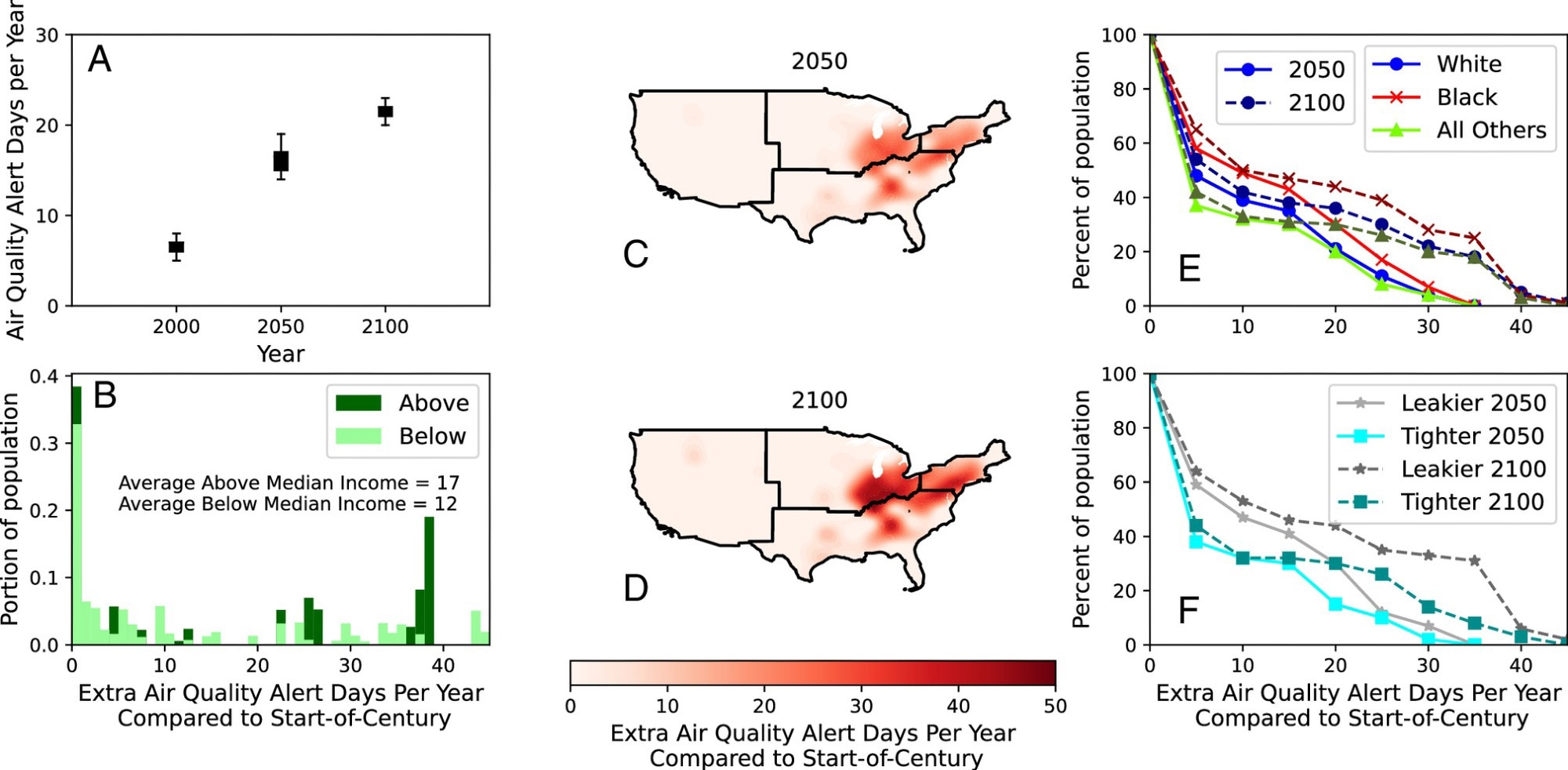

The study found that the rate of air quality alerts can increase by 4-fold on average by 2100 if the emission of greenhouse gases and air pollutants (particulate matter) is not reduced. Air quality alerts could increase by one month per year by 2100 in the eastern United States, representing the regions with high Black populations and poorly-housed populations.

As mentioned by the scientists, such unequal increases in air quality alerts in these low-income regions can adversely affect the adaptation capacity of vulnerable populations to poor air quality. Poorly structured houses can make the adaptation less effective or even harmful by letting polluted air infiltrate the houses and reduce indoor air quality.

Air quality alert days per year (ADY) rise in the absence of emission reductions. All plots show air quality alerts (defined as outdoor fine particulate matter levels resulting in an Air Quality Index > 100) for the Reference (REF) climate change scenario. (A) National mean population weighted ADY for 2000, 2050, and 2100. Plots (B–F) show Extra ADY (EADY) compared to start-of-century (B) Histogram of EADY in 2100 for population above and below median income. (C/D) Spatial change in EADY in 2050 and 2100. (E) Cumulative density of EADY by race in 2050 and 2100. (F) Cumulative density of EADY by residential leakage rates above (“Leakier”) and below (“Tighter”) the national average. Leakage is defined as air changes per hour at a 50 Pa pressure difference (ACH50), indicating greater infiltration of outdoor air inside.

Air quality alert days per year (ADY) rise in the absence of emission reductions. All plots show air quality alerts (defined as outdoor fine particulate matter levels resulting in an Air Quality Index > 100) for the Reference (REF) climate change scenario. (A) National mean population weighted ADY for 2000, 2050, and 2100. Plots (B–F) show Extra ADY (EADY) compared to start-of-century (B) Histogram of EADY in 2100 for population above and below median income. (C/D) Spatial change in EADY in 2050 and 2100. (E) Cumulative density of EADY by race in 2050 and 2100. (F) Cumulative density of EADY by residential leakage rates above (“Leakier”) and below (“Tighter”) the national average. Leakage is defined as air changes per hour at a 50 Pa pressure difference (ACH50), indicating greater infiltration of outdoor air inside.

Adaptation to air pollution versus mitigation of air pollution

Adverse health effects and premature mortality risks associated with air pollution can be reduced by reducing exposure to polluted air (adaptation) or reducing the emission of greenhouse gases and air pollutants (mitigation). These two strategies were compared in this study.

The findings revealed that adaptation offers more benefits than mitigation. However, a complete adaptation would require people to stay at home with windows and doors closed for an additional 142 days per year, which can only be achieved at an average cost of 11,000 USD per person. In contrast, reducing emissions can provide significant annual health benefits at an average cost of 5,400 USD per person.

The findings also revealed that combining adaptation and mitigation can provide the highest total benefits. The combination of these strategies could reduce the effectiveness of each strategy when used alone.

Although the study analysis indicated that mitigation is more cost-effective than adaptation, it remains highly uncertain to what extent mitigation of air pollution is possible and how it will ultimately affect outdoor air pollutants. These uncertainties demand for an induction of individual adaptation.

Regarding the benefits of adaptation, the study found an average benefit of 31 USD per person per hour for adults aged 30 years and above. Thus, an appropriate adaptation policy and mitigation strategies are needed to effectively and equitably protect general and vulnerable populations from air pollution.

According to the study findings, adaptation could be more beneficial for people who live in polluted areas, work or live in high-quality buildings, or do not value their outdoor time despite regularly spending time outdoors. Furthermore, the study projected that people who never spend time outdoors, live in poorly structured houses, or highly value their outdoor time would not benefit from additional adaptation.

Overall, the study indicates that new policies are needed to increase adaptation rates and maximize protection from air pollution. New policies could compensate people for moving indoors, improve house quality, provide measures for people who work or live outdoors, and increase awareness about air quality alerts and adaptation strategies.