Toilet flushes are known to produce aerosols, which could carry pathogenic viruses to various surfaces in the restroom. A new study in the American Journal of Infection Control examines the impact of closing the toilet lid before flushing on the odds of cross-contamination of other surfaces.

It has been demonstrated that people with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in their feces. Similarly, viruses in urine and feces may be released during toilet flushing, contaminating surfaces. Such fomites may transmit infection.

Household sewage contains almost any human pathogen and may cause the spread of such disease-causing organisms via aerosol formation. Such aerosols, as well as droplet nuclei, have been found in the environment after long periods and can be carried via air currents to other surfaces, causing long-distance transmission of such pathogens.

Toilet flushing as a medium of viral transmission was first thought to be via particulate fecal matter containing pathogens, and the areas studied were toilet surfaces. While some research indicated that pathogens were less likely to aerosolize and contaminate toilet surfaces during flushing if the toilet lid was down, this was also the case if disinfection was performed.

In the US, public and private toilets both create high-velocity airflow aerosols that may carry viruses from the water in the toilet bowl to significant heights, facilitating the spread of viruses within the room. The current study was meant to demonstrate how far the toilet lid shut down when flushing contained the spread of viral contamination in household toilets and to identify the effect of toilet bowl cleaning with commercial disinfectant.

In order to detect contaminating bacteria, the researchers used bacteriophage MS2 as a contaminant, adding it to toilet bowls in household and public restrooms.

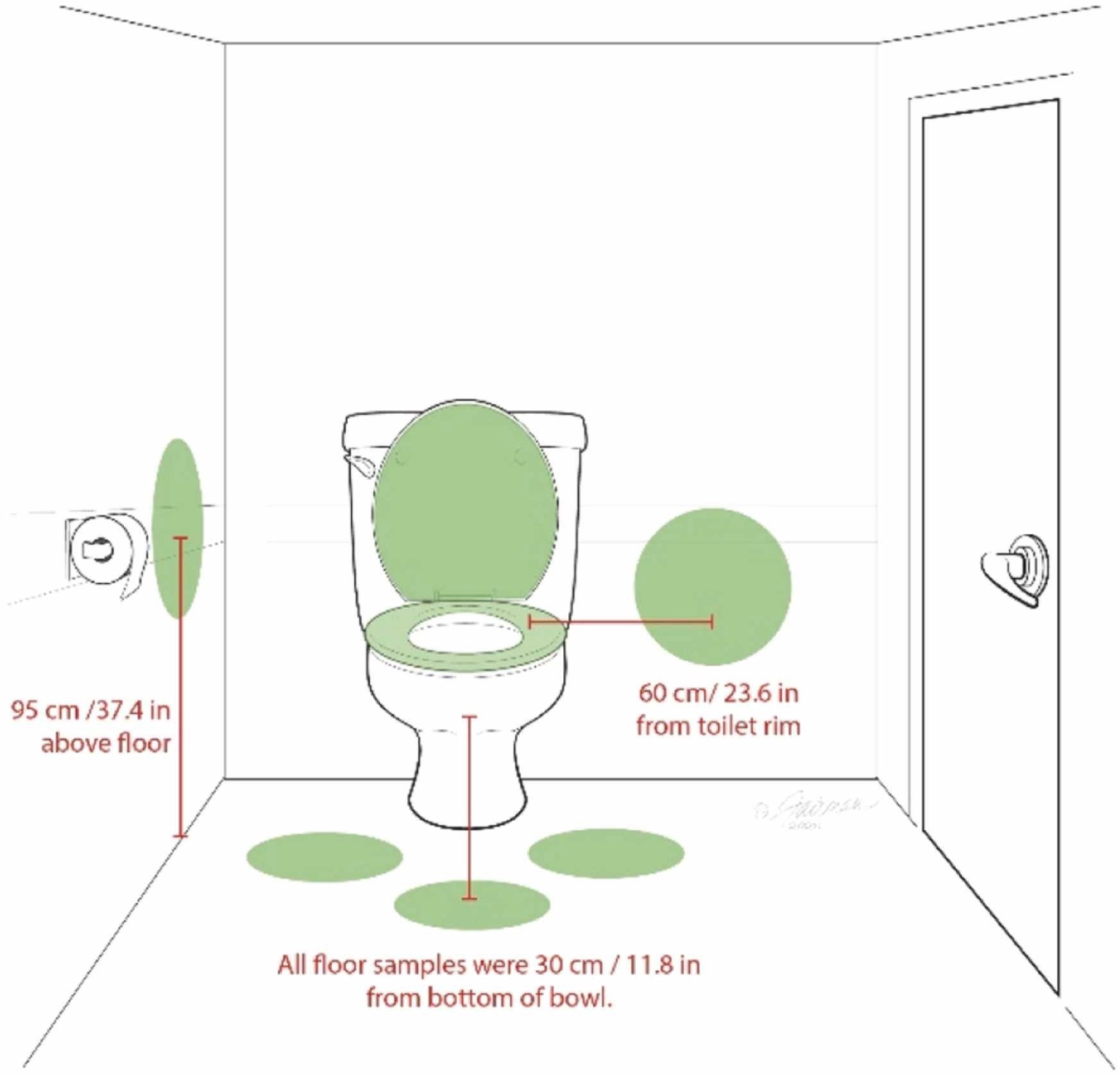

Schematic diagram of restroom sampling sites for toilet flushing aerosol and lid closure experiment.

Schematic diagram of restroom sampling sites for toilet flushing aerosol and lid closure experiment.

What did the study show?

The toilets were inoculated with MS2 at two dosages. They were flushed, and samples were taken for culture. Sampled areas comprised toilet bowl water, the tops and bottoms of the toilet seats, and selected spots on the floor in front, on either side and on the walls on either side.

In addition, the toilet bowl water after brushing without disinfectant, toilet bowl brush, and caddy were also sampled with the toilet rug.

At this step, contamination occurred at a mean of 107 PFU/100 cm2. This value remained stable whether the toilet seat lid was up or down. However, the main contamination was on the bottom of the toilet seat with high-dose MS2, with the lid top and bottom remaining at low contamination levels in either position.

Interestingly, wall and floor contamination did not change with either lid position, though it was minimal for the former. Paradoxically, the floor to the right and left were less contaminated with the lid up and the wall on the left more.

The same patterns persisted when the toilet bowl was cleaned with a brush.

In the next step, the toilet bowls were scrubbed using a bowl brush and a disinfectant, hydrochloric acid. This resulted in a marked reduction in contamination of the toilet bowl water by over 99.99% (a >4 log10) when compared to brushing without a disinfectant. The bowl brush contamination was reduced by 97.6% with the use of the acid vs. no disinfectant.

Other surfaces, including the brush holder, bowl rim, toilet seat, lid, or floor, did not show any difference in contamination levels.

What are the implications?

The current study looked at small droplet dispersion in aerosols rather than large droplets containing fecal matter. “These results demonstrate that closing the toilet lid prior to flushing does not mitigate the risk of contaminating bathroom surfaces.”

With a higher level of toilet bowl water contamination, the lower surface of the seat was more heavily contaminated. Public toilets in the US have no lids; thus, the seats were always highly contaminated after flushing, even at lower levels of virus in the water. Viral particles may be more readily and widely spread via aerosolization than bacteria because of their increased viability and ease of aerosol formation.

The toilet design in the USA contributes to significant contamination of the toilet seat because of the airflow during flushing, over both aspects of the toilet seat and through the 0.5-inch gap from seat to toilet rim, towards the floor and walls.

To prevent contamination, viruses in the bowl water can be inactivated or removed by cleaning the bowl with hydrochloric acid and a bowl brush.

With newer and potentially or actually very deadly viruses (like the Ebola virus) being transmitted across the world, just a few particles may suffice to infect a human host. The best practice with infection in the household causing gastric and intestinal upsets might be “regular disinfection of all restroom surfaces following toilet brushing, and/or use of a disinfectant that leaves residual microbicidal activity.” This is especially important when immunocompromised patients are in contact with the index patient.