Their findings highlight the subjective nature of listening to music while also showing that some associations between music and the emotional and bodily responses it elicits transcend cultural boundaries.

Study: Bodily maps of musical sensations across cultures. Image Credit: fizkes / Shutterstock

Study: Bodily maps of musical sensations across cultures. Image Credit: fizkes / Shutterstock

Background

Certain universal responses to music emerge as early as infancy, including moving foot tapping and head nodding. Music is known to activate the brain regions that control sensory-motor responses even without movement and can alter the autonomic nervous system (ANS) by affecting respiration, heart rate, and body temperature. Concurrently, it can elicit endocrinological responses such as modifying oxytocin and cortisol levels.

The ubiquitous nature of these responses suggests that music may serve an important but still unknown evolutionary function. This hypothesis is strengthened by the observation that music and dance are central to social life in cultures around the world. Previous research has shown that there are cross-cultural similarities in non-music-related emotions, but the consistency of bodily sensations evoked by music across cultures has not been examined.

About the study

In this study, researchers explored how acoustic features and emotional characteristics of music induce different subjective body sensations. To see if these effects were consistent across cultures, the study included both Western participants from Western Europe and the United States and East-Asian participants from China.

The music database included 72 songs, half of which were Western and the other half Chinese. The songs were categorized as sad, happy, tender, aggressive, tender, and groovy (danceable). Each participant completed 12 trials; in each, a music clip was played, and they were given a black outline of a human body. They were told to mark the parts of the body which they felt were stimulated by the music.

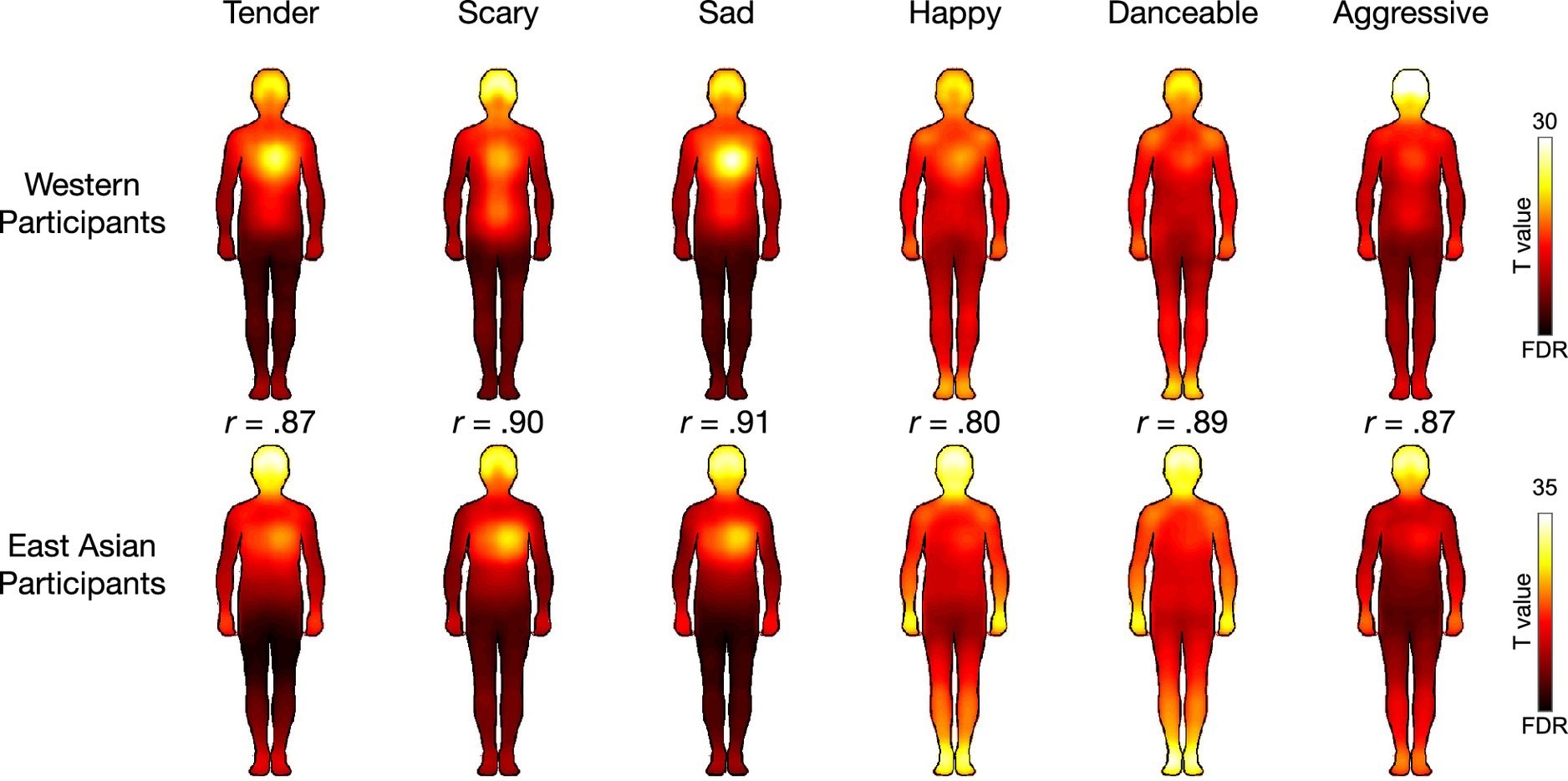

Topographies of bodily sensations evoked by each song category in Western and East Asian listeners. The maps show regions whose activation increased when listening to songs in each category (averaged over songs within each category, P < 0.05 FDR corrected). The correlation coefficients indicate the correlation between the BSMs of Western and East-Asian participants for each emotion.

Topographies of bodily sensations evoked by each song category in Western and East Asian listeners. The maps show regions whose activation increased when listening to songs in each category (averaged over songs within each category, P < 0.05 FDR corrected). The correlation coefficients indicate the correlation between the BSMs of Western and East-Asian participants for each emotion.

The researchers used these figures to generate bodily sensation maps (BSMs). These were analyzed to quantify the effect of the different music categories, accounting for the cultural group (Western/East-Asian) of the listeners. In a separate experiment, a different set of participants was asked to rate songs from the same dataset on likeability, familiarity, sadness, happiness, aggressiveness, tenderness, and grooviness, as well as how energetic, relaxed, and irritated it made them feel.

Findings

Subjective feelings towards the music by East Asian and Western participants were highly correlated, suggesting that individuals across the two cultures had consistent emotional experiences. The primary difference was in terms of familiarity, as Western participants were more familiar with Western songs than East Asian songs, and vice versa.

The findings from the BSMs indicated that participants felt the effects of the sad or tender songs in their head and chest area; particularly in Western participants, the effect of the scary songs was felt in the gut. The effects of danceable and happy songs were felt all over the body but concentrated primarily in the limbs. Music categorized as aggressive was also felt all over the body, but especially in the head.

The key difference between East Asian and Western participants in the BSMs was that the former reported more consistent activation in the head, legs, and arms across the categories. Participants from Western countries also reported feeling more consistently activated in the chest area for sad and tender songs.

Similarity matrices showed high levels of correlation and cross-correlation across East Asian and Western participants for the BSMs and emotional dimension ratings. Notably, the same musical features were associated with dimensions of irritation, aggressiveness, scariness, energization, danceability, tenderness, sadness, and happiness by individuals of both cultures. For example, tenderness and sadness were associated with slight harmonic changes, low roughness, and clear keys, while unclear keys and complex rhythms were associated with scariness or aggressiveness.

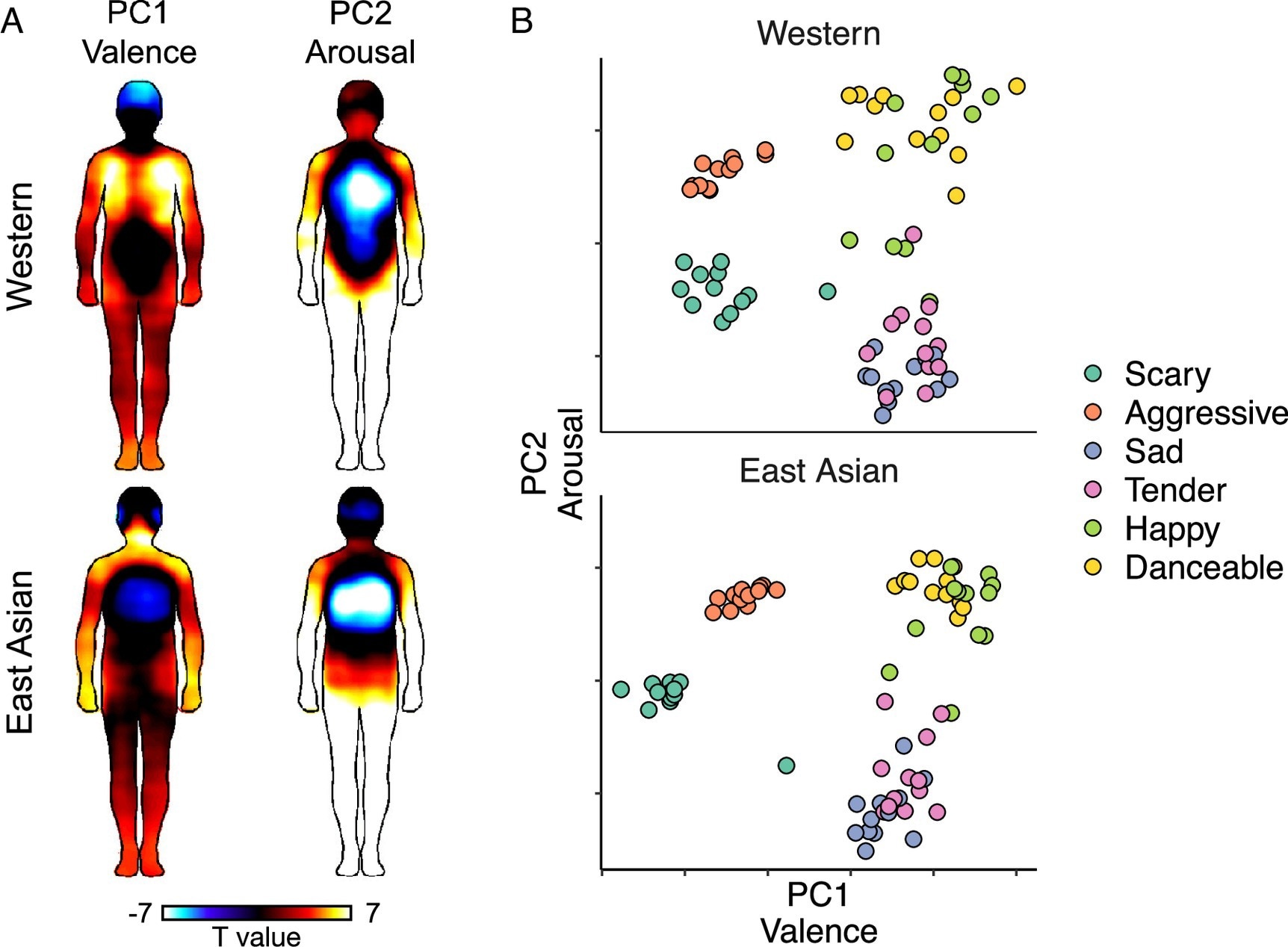

(A) BSMs for PC1 (Valence) and PC2 (Arousal) in Western and East Asian participants (P < 0.05 FDR corrected). (B) Song-wise PC scores.

(A) BSMs for PC1 (Valence) and PC2 (Arousal) in Western and East Asian participants (P < 0.05 FDR corrected). (B) Song-wise PC scores.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that the emotions and bodily sensations that music evokes are consistent across cultures. They also emphasize how music can bring out strong but subjective bodily sensations, which are highly associated with the emotional and auditory experience.

The authors note that their study is limited by its focus on only two distant (but not isolated) cultures and can, therefore not capture other culture-dependent variations. Future research could add to this body of knowledge by considering several cultural groups and examining how their responses vary from each other along a continuum of distance. Another fundamental limitation is that information on bodily sensations was self-reported – future work in this area could also collect data on physiological changes.