Compared to offspring of other animals, human infants are born with fewer basic survival skills such as walking and feeding; therefore, acquiring protection and care from adults is vital to their survival. However, although maximum investment from the parents in its care is beneficial for the infant, dividing the investment equitably among all the offspring across the lifetime of the parent is the more optimal evolutionary strategy for the parents.

As a response to this conflict, certain strategies have evolved in infants to promote more investment from the parents in their care. Human infants display a set of specific physical traits that trigger nurturing behavior in adults. Human parents have also evolved strategies to read physical and behavioral cues to make informed decisions about investing in the infant's welfare.

The concept that facial features of infants have evolved to evoke psychological, physiological, and neurological responses that induce impressions of "cuteness" and result in increased parental care is known as 'baby schema,' a term introduced by the Austrian ethologist and zoologist Konrad Lorenz. In the present review, the authors address the inconsistencies in the usage of the term' baby schema' across studies and explore existing evidence for baby schema among humans and other animals.

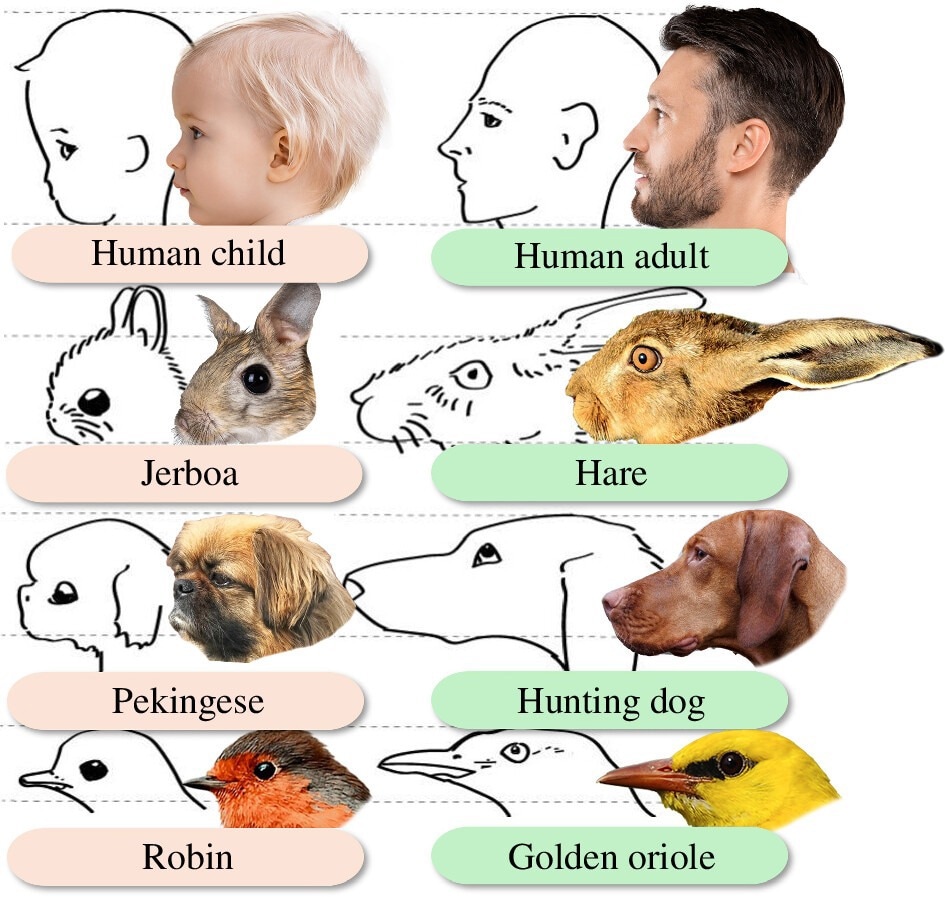

The original line drawing illustration of the baby schema, corresponding photographs added). The original illustration captures ‘the releasing schema for human parental care response. Left: head proportions perceived as ‘lovable’ (child, jerboa, Pekinese dog (sic) robin). Right: related heads that do not elicit the parental drive (man, hare, hound, golden oriole)

Inconsistent usage of terminology

The reviewers believe that one of the possible causes of the confusion and inconsistency in the usage of the term baby schema could be that the original article in which Lorenz discussed the concept of baby schema was published in German.

The review found that subsequent studies describing baby schema had additional features not mentioned in Lorenz's original article. Furthermore, Lorenz's original description of baby schema included characteristics not related to facial features, such as body movement, texture, and shape, which were not included in later studies.

Furthermore, the caption, which has been largely overlooked in subsequent studies, indicated that Lorenz was not comparing the young and adults of humans and various other species but comparing the cute and not cute pairs of related species to juxtapose the features of human young and adults.

Later studies have also been inconsistent in the manner in which the term has been used. Some studies have described baby schema as a categorical term referring to infant features as compared to adult features that do not elicit the same emotional responses. Others have used it to depict a continuous spectrum, where baby schema is the degree to which facial features add to the cuteness perception and can also apply to adults.

Baby schema in humans and other animals

Studies that explored baby schema as a categorical term reported that infants' faces received more attention than adult faces, and female participants paid more attention to infant faces than adult faces than male participants did. Magnetoencephalography-based studies also showed that the medial orbitofrontal cortex, which is involved in reward processing, showed more brain activity in response to infant faces than adult faces.

Examining baby schema as a spectrum also showed that infant faces that had narrower and shorter features, such as a large forehead and large eyes, were rated as cute. Furthermore, wider faces with smaller noses and mouths, bigger eyes, and a large forehead were rated to have a greater baby schema. Such faces were also found to be cuter and elicit greater caretaking behavior in participants.

The concept of baby schema is not limited to human faces, and studies have explored humans' perceptions of cuteness toward other animals. One study tested human perceptions toward images of young animals of species where the young require parental care (semi-precocial) and species where the young do not require parental care (super-precocial).

The participants found the young of semi-precocial species as having more baby schema than those of super-precocial species, which has been argued as evidence of convergent evolution of baby schema in other species, where neotenous features in young animals have evolved to elicit caregiving responses. However, the findings on whether human responses to neotenous features and baby schema are innate or develop with time remain unclear.

Studies also found mixed findings on the occurrence of baby schema among other animals. A few behavioral studies found that some primates, such as Japanese macaques, Campbell's monkeys, Barbary macaques, and chimpanzees, viewed infants for longer periods than adults in free-viewing tasks. However, the behavior was not observed in bonobos.

The researchers believe that a high degree of baby schema observed in humans could be an evolutionary response and adaptation to the degree of helplessness human babies exhibit in comparison to the young of other species.

Conclusions

In summary, the review examined the potential causes for the inconsistent usage of the term' baby schema' in the studies following Konrad Lorenz's coining of the term. Additionally, the researchers explored the evolutionary significance of baby schema by assessing whether neotenous features in human infants and young of other species elicited caregiving responses in adults.

To fully understand the implications of baby schema, further research is needed to investigate how these features influence behavior and perceptions across different species.