Scientists at the Babraham Institute, in collaboration with colleagues at the Cambridge Stem Cell Institute and the European Bioinformatics Institute, have made a breakthrough in stem cell research. Their paper, published today in Cell, describes how human stem cells can be reverted back to non-specialised cells.

Non-specialised stem cells are unique in their ability to reproduce by cell division without losing their undifferentiated state, ie, having no characteristics indicative of a specific cell lineage, such as nerve cells, muscle cells etc, and their unrestricted potential (pluripotency) to develop into any mature cell type. These characteristics make them invaluable for a range of medical therapies, eg, bone marrow transplantation.

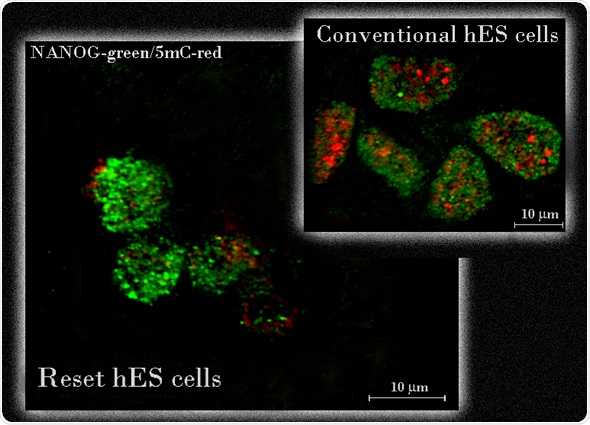

Human embryonic stem (hES) cells identified with a pluripotency marker (NANOG, in green), showing reduced DNA methylation (red) in reset cells. 3D rendering of confocal images. Image Credit: Babraham Institute

Finding that human stem cells can be reverted back to a naïve pluripotent state opens up the exciting potential for generating base-state, naïve human stem cells for future medical applications. Professor Wolf Reik, Group Leader at the Babraham Institute explained “We can liken this reprogramming to giving cells amnesia so they forget any previous developmental decisions they have made. Returning them to this state means that we can then control their cellular decisions, allowing us to generate the particular types of cells needed. This area has huge medical potential, for example, being able to provide reset stem cells back to a patient that we can be confident will develop into the correct cell type as required, for example, nerve cells.”

The epigenetic (non-sequence based DNA modifications that affect gene expression, eg, chemical methyl tags) regulation of base-state human stem cells was also analysed as part of the study. Epigenetic markers are acquired by a cell as it assumes a specific cell identity. Consequently, early embryo cells have few methyl tags as they are not yet committed to becoming a particular cell type. In this study, it was shown that the reset human stem cells had lost methylation marks throughout their genome, making them similar to similarity to early embryonic cells. In effect, their epigenetic memories had been erased. In addition, the group had already reported the large-scale loss of methylation from the genome of reset mouse embryonic stem cells. Observing low level s of DNA methylation in the reset human cells thus provided a strong indication that they had regained pluripotency.

Dr Gabriella Ficz, a member of the team who undertook the epigenetic analysis said: “This study brings us one step closer to the ultimate aim in regenerative medicine of using patient-derived cells to avoid immune rejection in cell and organ replacement therapies. It’s all about finding out what the cell needs in order to survive and multiply while making sure that they have lost the memory of the tissue they came from. Both conditions need to be fulfilled for successful use of embryonic stem cells in tissue generation.”

Source:

: Takashima et al. Resetting transcription factor control circuitry towards ground state pluripotency in human. Cell 2014. Available at: http://www.cell.com/cell/abstract/S0092-8674(14)01099-X