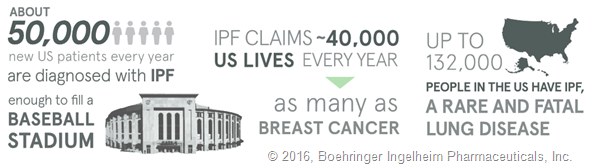

IPF is a rare and fatal lung disease that causes permanent scarring of the lungs, leading to debilitating shortness of breath and cough in affected patients. It affects as many as 132,000 Americans, most commonly those over the age of 65.

Because IPF is a rare condition, there is relatively little public awareness of the disease, and even in the healthcare community there are significant gaps in understanding about how to best recognize and treat the disease.

Can you please give an overview of the IPF-PRO Registry? What do you hope to learn about the outcomes and disease progression for people with IPF?

The Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis - PROspective Outcomes (IPF-PRO) Registry is a repository of patient data created through an alliance between Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) and Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI).

Building on existing knowledge from single-center studies and clinical trials, this registry is a prospective, multicenter effort designed to better understand the natural progression of IPF and the strategies used to diagnose and treat IPF in everyday clinical practice.

The study is led by co-medical directors Dr. Craig Conoscenti (BI) and Dr. Scott Palmer (DCRI).

Over time, through IPF-PRO, we look forward to helping the IPF community learn more about disease progression and how the disease impacts quality of life, as well as other outcomes that are important to patients.

How many people have enrolled in the registry so far and what results have been shown?

From an evaluation of the first 49 people with IPF enrolled in the registry, the results show:

- Most people exhibited symptoms of IPF for more than a year

- By the time of enrollment, many people exhibited considerably impaired lung function.

- Twenty-nine percent (14 patients) required supplemental oxygen when resting, and 45 percent (22 patients) required supplemental oxygen during activities.

We now have nearly 300 patients enrolled, and look forward to sharing more results about their clinical course over time.

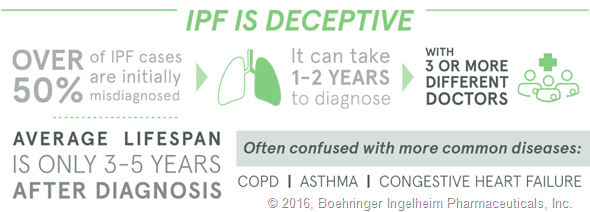

Why do you think many people exhibited symptoms of IPF for more than a year before being diagnosed?

First, IPF is a relatively uncommon disease, so healthcare providers will often consider more common conditions, like heart disease or COPD, first.

However, as our study has shown, some patients continue to have symptoms that are not entirely explained by these more common conditions, and increasing awareness of IPF and how it can be diagnosed may help these patients receive appropriate treatment more quickly.

Were you surprised by these results or does this back-up previous findings?

These results are meaningful, but not especially surprising. Other studies have shown similar delays in diagnosis.

For example, the recent EXPLORE IPF patient and caregiver survey conducted by Boehringer Ingelheim found that people with IPF experience symptoms for 1.9 years, on average, before receiving a proper diagnosis.

Patients enrolled in INSIGHTS-IPF, a prospective European IPF registry, had symptoms for more than 2 years prior to diagnosis.

Caring for Someone with IPF

What can be done to reduce the time it takes for patients with IPF to be diagnosed?

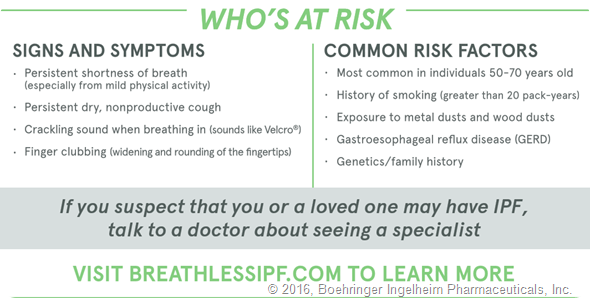

I would encourage medical providers to learn more about the basics of IPF. When patients’ symptoms or characteristics don’t quite fit more common diseases, or when patients don’t respond as expected to treatments for common diseases, providers should have a lower threshold to consider less common diseases like IPF. In these cases, referral to a pulmonologist with experience in interstitial lung diseases like IPF is crucial.

Additionally, patients with persistent symptoms can ask to see a lung specialist or pulmonologist, who is trained to identify the subtle differences between IPF and other respiratory diseases.

What impact does early diagnosis have?

Early diagnosis can help people with IPF get the proper care and treatment they need. There are IPF treatments available, including supplemental oxygen, cough medications, and pulmonary rehabilitation that can include special exercises or breathing strategies. And in 2014, the FDA approved the first drugs for the treatment of IPF.

Finally, some patients may be candidates for lung transplantation. While this option is ideally reserved for patients who worsen despite other treatments, sometimes IPF progresses very rapidly, and being diagnosed early and cared for by an experienced provider can help patients get access to a transplant center in a timely manner.

What further research is needed to increase our understanding of IPF?

We need to better understand how this disease progresses across the broad population of patients with IPF, to understand how treatments are being used in everyday clinical practice, and how the disease and treatments affect symptoms and quality of life over time.

In addition, there is a great need for better blood or genetic markers that might help diagnose IPF earlier or predict how it will progress. As IPF-PRO continues, we look forward to addressing many of these questions to help improve the lives of patients with IPF.

Where can readers find more information?

For more information about IPF, including signs and symptoms, visit www.BreathlessIPF.com.

About Michael Durheim, M.D.

Medical Instructor, Department of Medicine, Duke Clinical Research Institute

Medical Instructor, Department of Medicine, Duke Clinical Research Institute

Dr. Durheim is a pulmonologist who treats patients with IPF and other interstitial lung diseases at Duke University Medical Center. He is an active clinical investigator involved with research in IPF and lung transplantation.

Dr. Michael Durheim is an instructor of medicine in the division of pulmonary, allergy and critical care medicine at Duke University Medical Center, where he sees patients in the interstitial lung disease and lung transplant programs. He is a faculty member at the Duke Clinical Research Institute, where his work is focused on patient-centered outcomes research in interstitial lung disease, other advanced lung diseases, and lung transplantation.