Oct 4 2016

Recent work has shown that Zika virus persists in semen for up to 6 months after infection. In a correspondence published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, the researchers, in addition to confirming its long persistence in semen (in this case for more than 130 days, i.e., over 4 months), reveal the presence of the virus even within spermatozoa. This work results from collaboration between researchers from Inserm, CNRS, and academic practitioners from University Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier and Toulouse University Hospital.

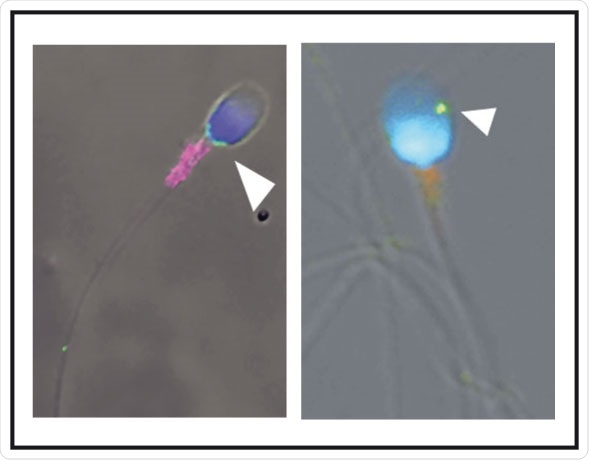

Spermatozoa infected by Zika virus (green; arrowhead). © Elsa Suberbielle, CPTP / Inserm

In this letter, the scientists report the case of a 32-year-old man returning from French Guyana with symptoms suggestive of Zika virus infection, namely, moderate fever, rash, and muscle and joint pain. Zika virus was detected in the patient's plasma and urine 2 days after the onset of these symptoms. Samples of semen (11 samples), blood (10) and urine (5) were taken and analysed over a total period of 141 days.

Upon analysis, Zika virus was found to be present in all samples up to the 37th day. Beyond that point, the virus was found only in the semen, where it persisted for over 130 days, while the patient was in good health. This result was confirmed in two other patients, in whom the virus persisted for 69 and 115 days in the semen. For the moment, the factors responsible for this variation in persistence amongst individuals are unknown. From the time of diagnosis, however, these patients were advised to use protection during sexual relations.

The research team subsequently analysed the semen from the patient and examined the spermatozoa it contains using various microscopy techniques.

“We detected the presence of Zika virus inside approximately 3.5% of this patient’s spermatozoa,” explains Guillaume Martin-Blondel, Inserm researcher at the Toulouse Purpan Pathophysiology Centre (Inserm/CNRS/University of Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier) and physician at the Infectious and Tropical Diseases Department of Toulouse University Hospital.

The researchers explain that for other sexually-transmitted viruses, such as HIV, the virus remains “stuck” at the surface of spermatozoa. For purposes of in vitro fertilization, it is therefore possible to “wash” the spermatozoa from HIV-infected patients, whereas this seems to be excluded for patients positive for Zika virus. However, the “active” nature of the Zika virus present in spermatozoa remains to be determined, as well as the ability of these spermatozoa to transmit infection (since the virus is also present outside the spermatozoa, in the seminal fluid).

In conclusion, analysis of this case has important implications for the prevention of sexual transmission of this virus, by means that remain unknown at present. These observations also raise many questions on the need to include screening for Zika virus in the testing of sperm donations in fertility centres.