Nov 30 2016

Researchers at Okayama University have successfully cleaved influenza viral RNA to prevent its replication using novel artificial RNA restriction enzymes in laboratory cell cultures. While further improvements are needed, the findings show great promise and could lead to anti-viral drug development in future. The findings are published in Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, October 2016.

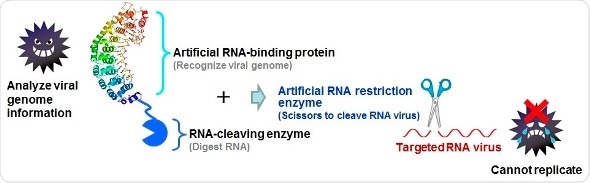

Analyse virus gene information and create an artificial RNA restriction enzyme. Viruses cannot replicate as their gene information is cleaved (which means virus cannot cause diseases). This technique can be applied to all kinds of RNA viruses both for animals and plants.

Developing technologies that can inactivate viruses and prevent them from infecting humans could transform the way in which we tackle various diseases. Several methods aiming at inactivating viruses have been tried, including preventing the binding of viral proteins and using artificial enzymes to ‘cleave’, or split, molecules in viral genomes.

By splitting a chosen molecular strand, such as DNA or RNA, essential bonds are broken and the molecule can no longer function correctly. In the case of viruses, integrating DNA or RNA cleaving ability into anti-viral drugs could prevent viral replication and infection within a host. Following recent success cleaving DNA in the human papillomavirus, Takashi Sera and co-workers at Okayama University have now used the same technique to cleave RNA in influenza cell cultures.

Firstly, the team developed artificial RNA restriction enzymes. These enzymes incorporate an artificial RNA binding protein, whose job is to target the correct virus, and an RNA cleaving enzyme that targets a specific domain in the viral RNA in order to create the split. Enzymes created for previous studies targeted the viral PIN domain but with limited success, and so Sera’s team created new RNA restriction enzymes targeting the staphylococcal nuclease (SNase) domain instead.

The researchers compared the ability of the SNase-based enzymes to cleave influenza RNA with PIN-fusion enzymes. They found that the SNase enzymes recognized and completely cleaved their target RNA in five minutes in cultures in the lab; in fact, the SNase enzymes had higher cleavage rates in one minute than the PIN-fusion enzymes had in two hours.

With improvements to the enzymes for use in animal (and eventually human) cells, the SNase restriction enzyme technique could one day prove to be a very powerful tool in the development of anti-viral drugs.

Background

DNA and RNA viruses

Viruses have either DNA or RNA as their genomes. Examples of DNA viruses include herpes, chickenpox and smallpox – they replicate in nuclei after infiltrating host cells. RNA viruses, on the other hand, inject their RNA into host cell cytoplasm where it is then used to synthesize proteins and form replica viruses. RNA viruses include influenza, HIV and Ebola, to name but a few.

Scientists are keen to find ways of preventing both DNA and RNA viral infection and replication inside the body. Such technology could transform the way in which we tackle various diseases. One feasible way of stopping viral replication is to target the genetic machinery involved in the process – namely by cleaving, or splitting, the DNA or RNA strands so that they can no longer function correctly.

The techniques developed by Takashi Sera and his team at Okayama University involves the creation of artificial restriction enzymes – carefully-designed molecules incorporating proteins and enzymes that can home in on, and cleave, specific RNA or DNA targets. Their previous studies have been successful in cleaving DNA in human papillomavirus, and now they have used the same technique to cleave RNA in influenza cell cultures.

Implications of the current study

Following further work on the RNA restriction enzymes to ensure they are effective and safe for use in animal (and eventually human) cells, the team hope that their technique could lead to future development of anti-viral drug. Their findings represent a significant step forward in realising this goal.