May 30 2017

The search to develop a HIV cure has long been overwhelmed by a seemingly simple question: How do physicians find out if somebody is cured? The virus has an ability to lie dormant in immune cells at levels that could not be detected to all, however, the most expensive and time-consuming tests can find the hidden virus.

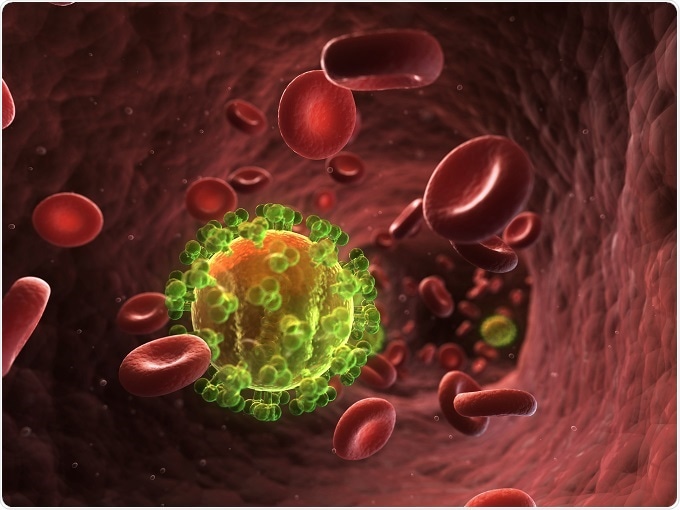

Credit: Sebastian Kaulitzki/Shutterstock.com

Credit: Sebastian Kaulitzki/Shutterstock.com

According to a study published in Nature Medicine, scientists at the University of Pittsburgh's Graduate School of Public Health have created a test sensitive enough to detect “hidden” HIV. The test, which is faster, less labor-intensive, and less expensive than the current “gold standard” test, has revealed that the amount of virus lurking dormant in HIV people appearing to be nearly cured is about 70-fold larger than previous estimates.

"Globally there are substantial efforts to cure people of HIV by finding ways to eradicate this latent reservoir of virus that stubbornly persists in patients, despite our best therapies," said senior author Phalguni Gupta, Ph.D., professor and vice chair of Pitt Public Health's Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology. "But those efforts aren't going to progress if we don't have tests that are sensitive and practical enough to tell doctors if someone is truly cured."

CD4+ T cells are a type of white blood cell that plays a major role in protecting the body from infection. HIV is spread when CD4+ T cells are infected. The advancement in antiretroviral therapies to treat HIV has reached the point where HIV patients can have the virus so well controlled that they could have as little as one virus infection per million CD4+ T cells.

Yet the majority of HIV DNA integrated into these cells is defective, which means it would not cause infection anyway. When the HIV therapy starts working, it is important to find whether the HIV DNA that the test detects could in fact create more viruses and cause the person to relapse if therapy is stopped. Consequently, the test must be able to show that the detected virus can replicate, by growing the virus from the sample.

The best test available to do this, to date, is quantitative viral outgrowth assay (Q-VOA). The test has many disadvantages, such as it may provide only a minimal estimate of the latent HIV reservoir size, requirement of large blood volumes, labor intensive, time-consuming, and expensive.

The team led by Gupta have developed a test called TZA. The test works by detecting a gene that is turned on only in the presence of replicating HIV, thus the virus is flagged to be quantified by technicians.

Compared with Q-VOA tests where results are produced in 2 weeks, the TZA test results are produced in 1 week and at one-third of the Q-VOA test cost. Also, TZA requires smaller blood volumes and is less labor intensive.

Using this test, we demonstrated that asymptomatic patients on antiretroviral therapy carry a much larger HIV reservoir than previous estimates--as much as 70 times what the Q-VOA test was detecting. Because these tests have different ways to measure HIV that is capable of replicating, it is likely beneficial to have both available as scientists strive toward a cure."

Phalguni Gupta, Ph.D, professor and vice chair of Pitt Public Health's Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology

As TZA tests have a low cell requirement, TZA may be useful for replication-competent HIV-1 quantification in the pediatric population, as well as in the lymph nodes and tissues where the virus persists.