American Scientists have managed to edit and improve the DNA of human embryos in an effort to correct the gene defects that cause inherited diseases.

The DNA of human embryos has been edited previously by scientists in China, but this is thought to be the first time the controversial practice has been carried out in the US.

The work by Shoukgrat Mitalipov (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland) and colleagues is believed to be ground-breaking in terms of the number of embryos modified and the safety and efficiency that was demonstrated in doing so.

The object of altering human embryonic DNA is to correct or eliminate genes that lead to inherited diseases, such as the blood disorder beta-thalassemia. This gene modification process is referred to as germline engineering, since a person carrying the altered genes would pass the changes on to any offspring they had, via their own eggs or sperm (germ cells).

As reported in MIT Technology Review, Mitalipov and team managed to change the DNA of numerous one-cell embryos using a gene editing technique called CRISPR.

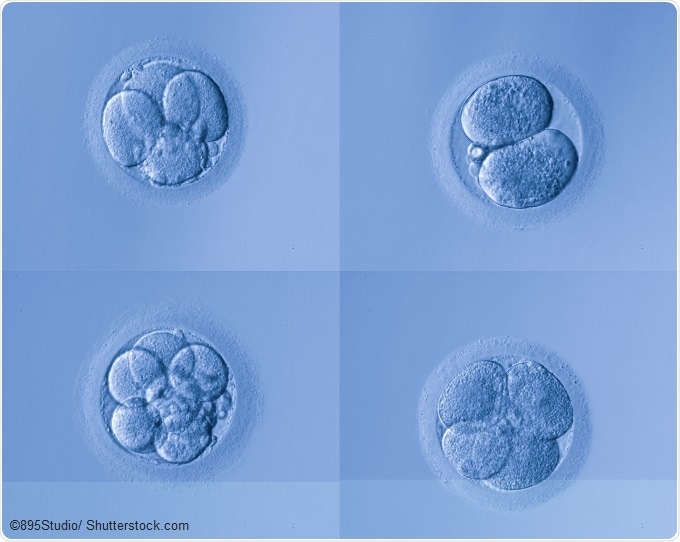

Chinese scientists had previously reported using CRISPR to edit human embryos, but they were only successful in altering a small number of cells. This effect, where some cells have a different genetic make-up to others is referred to as “mosaicism,” an effect that experts warned would make germline engineering unsafe for humans.

However, Mitalipov and colleagues have shown that because the CRISPR errors are known, it is possible to avoid this problem. The team reduced mosaicism by ensuring that CRISPR was injected into eggs early on, while they were in the process of being fertilized with sperm.

Although none of the embryos were allowed to develop beyond a few days, this breakthrough has meant scientists are now one step closer to achieving the birth of genetically modified human beings.

A scientist who is familiar with the project but chose to remain anonymous said: “It is proof of principle that it can work. They significantly reduced mosaicism. I don’t think it’s the start of clinical trials yet, but it does take it further than anyone has before.”