Researchers have developed organ chip technology using donor-derived human intestinal cells that offers advantages over organoids and provides new opportunities for personalized medicine.

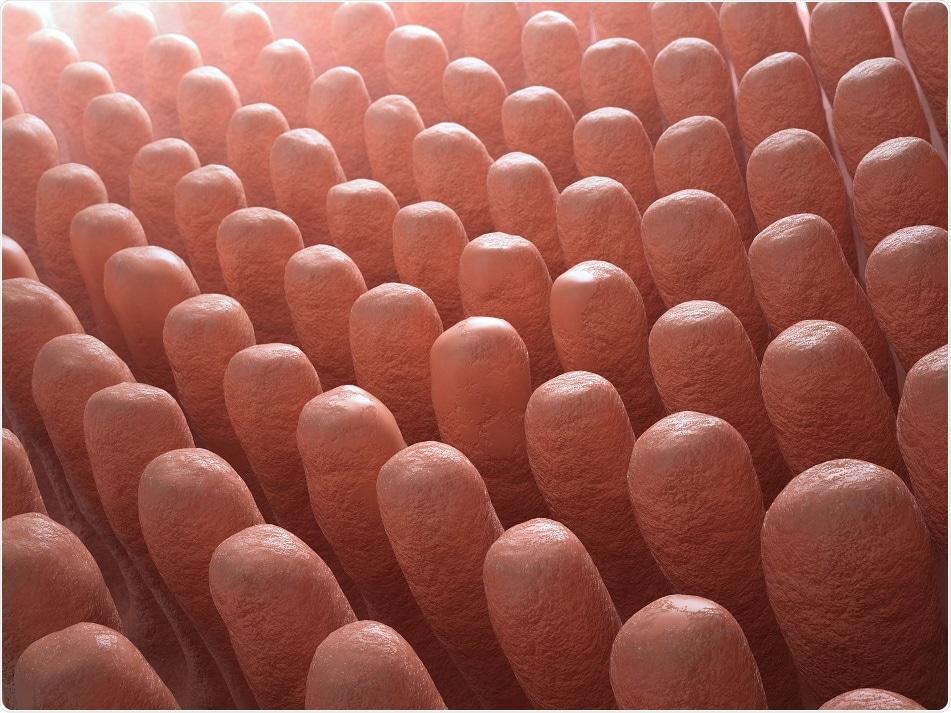

Inside the intestine villi. Credit: Mopic/ Shutterstock.com

To help improve understanding of how the small intestine operates in both health and disease, researchers had developed “organoids” by isolating intestinal stem cells from human biopsies.

Although these organoids form all of the cell types present in the intestine, they grow as cysts with their cell surface facing an enclosed lumen rather than being exposed to the content of the gut, thereby preventing the study of processes such as nutrient and drug transport, which involve the intestinal barrier.

Organoids also lack the vasculature and mechanical movements that occur in peristalsis and blood flow, which are needed for the gut’s regeneration and many other digestive processes. To address these problems, researchers from the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering created a microfluidic “Organ-on-a-chip” culture device.

Donald Ingber and colleagues isolated human intestinal cells from a tumor and cultured them in one of two channels separated by a membrane from blood vessel-derived endothelial cells in the adjacent channel.

This gut chip recreated the villus epithelium of normal intestine, meaning researchers could study peristalsis and intestinal function. However, it did not allow the study of processes that use normal intestinal cells from individual donors, which is crucial to analysing patient-specific responses for personalized medicine.

Now, Ingber and team have addressed this limitation by using the organoid approach to isolating intestinal stem cells from human biopsies, by breaking up the organoids and growing the patient-specific cells within the gut chip. Those cells spontaneously form intestinal villi that face the channel lumen and the epithelium in close apposition to human intestinal microvascular endothelium.

This approach presents a new stepping stone for the investigation of normal and disease-related processes in a highly personalized manner, including the transport of nutrients, digestion, different intestinal disorders, and intestinal interactions with commensal microbes as well as pathogens, “

Donald Ingber, the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering

Ingber's team is now applying the same approach to different parts of the intestine that differ in their function and disease vulnerabilities.

"In the future, such efforts could allow us to much better understand human-microbiome interactions, model malnutrition disorders and inflammatory diseases of the gut, and perform personalized drug testing," says co-first author of the study Alessio Tovaglieri (Department of Health Science and Technology at ETH Zurich, Switzerland).