Prions are proteins that are known to have some unique features. They differ slightly in structure from regular proteins and are self-propagating. When a prion meets another, non-prion protein, it causes a conformational change, turning the second protein into a prion.

Image Credit: Golba / Shutterstock

Image Credit: Golba / Shutterstock

These proteins are known to be the causative agent in several diseases, as was first demonstrated by Nobel Prize winner Stanley Prusiner in 1997 for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

Since this discovery, there have been a bunch of research articles highlighting the involvement of prions in other neurodegenerative disease such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease (ALS).

When it comes to Alzheimer’s disease, we know that the pathogenic driver of the condition is the formation of insoluble and neurotoxic misfolded proteins. One of these is the tau protein, and the other is amyloid-beta.

In Parkinson’s disease, a misfolded protein, alpha-synuclein, is highly neurotoxic and accumulation results in the disruption of neurons in the brain. All of these have been suggested to have a prion-like nature, with the only differences being the location of the proteins and their origins.

Are prions only found in mammals?

Yes, pathogenic prions are predominantly found in mammals. There is some research that suggests that they are present in organisms such as zebrafish, but prion biology has been much more extensively studied in mammals.

Please describe your recent research surrounding prion-like proteins in eukaryotic viruses.

We analyzed over two and a half million different proteins from eukaryotic viruses and discovered a very small region of these proteins that had prion-like properties. Viral proteins have never before been described in the literature, so it was a very exciting discovery for us.

In order to infect a human host, a virus must bind to proteins on the surface of host cells. We know that the proteins we looked at are involved in this process, so it wouldn’t be surprising if the prion-like domain played a role in the normal interaction of viral particles with the human cells. If proven to be correct, these proteins could prove to be a vital target for drug development.

The prion-like domain may also cause emerging viruses like the herpesviruses, Ebola or HIV to be pathogenic through novel interactions with host cells.

This opens up new possibilities to better understand how viruses affect our cells and how the pathogenicity of viruses develops.

Image Credit: Andrii Muzyka / Shutterstock

Image Credit: Andrii Muzyka / Shutterstock

What conclusions can be made from the research?

The major take-home message from our study is that viruses possess prion-like domains. We know that these domains are required for viral development and propagation, and think that they might be involved in viral interaction with host cells.

The second important point is that prion-proteins could represent novel therapeutic targets in the prevention and treatment of viral disease.

If we could inhibit the alteration of the conformational state of these prion-like domains within the virus, then we’ll most likely prevent interaction with the human host.

This is something we are very excited about and are currently working with different universities to prove.

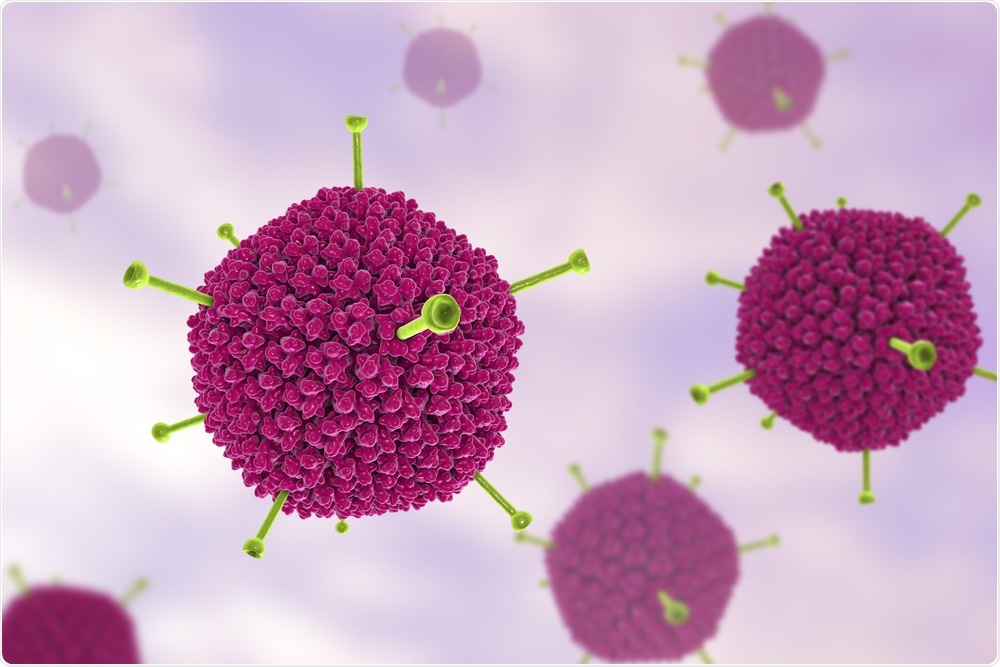

Finally, the presence of prion-like domains on the surface of viruses used as vectors for gene delivery (such as adeno-associated viruses) will most likely lead to the development of a new highly selective viral-based gene delivery system.

We have identified prion-like domains on the surface of adenoviruses that are commonly used in gene therapy as vectors for the delivery of therapeutic genes. This opens up the discussion for the modification of adenoviruses, by exploiting this property to increase transduction selectivity.

Adenovirus particles. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Adenovirus particles. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Will this research have any implications for neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease?

Yes. We are currently conducting a study into the possibility that viral prion-like domains play a role in initializing human protein misfolding in neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

What does the future hold for your research?

As I previously mentioned, the first avenue that we are exploring is prion-like proteins as a previously unknown therapeutic target, modifying which could prevent the infection of the host cell.

Secondly, we will be evaluating the possibility of using prion-like domains on the suface of viral vectors to increase the selectivity and cell type-specificy gene delivery

Finally, we have just started a project looking at the prion-like proteins as a previously unknown pathogenic trigger for human neurodegenerative diseases

Where can readers find more information?

Prion-like Domains in Eukaryotic Viruses. 2018. Scientific Reports (from the publishers of Nature).

About George Tetz

Dr. George Tetz, MD, PhD, is the Chief Scientific Officer for the Human Microbiology Institute, a not-for-profit New York based scientific research company which explores the cross-talk between the microbiota and the human body.

Dr. George Tetz, MD, PhD, is the Chief Scientific Officer for the Human Microbiology Institute, a not-for-profit New York based scientific research company which explores the cross-talk between the microbiota and the human body.

Dr. Tetz works on various projects related to microbiome and drug development and is pioneer in phagobiome and sporobiome research, including the discovery of previously unknown human bacterial pathogens.

He has over 17 years of experience in drug development and microbiological research, with over 40 peer-reviewed papers.