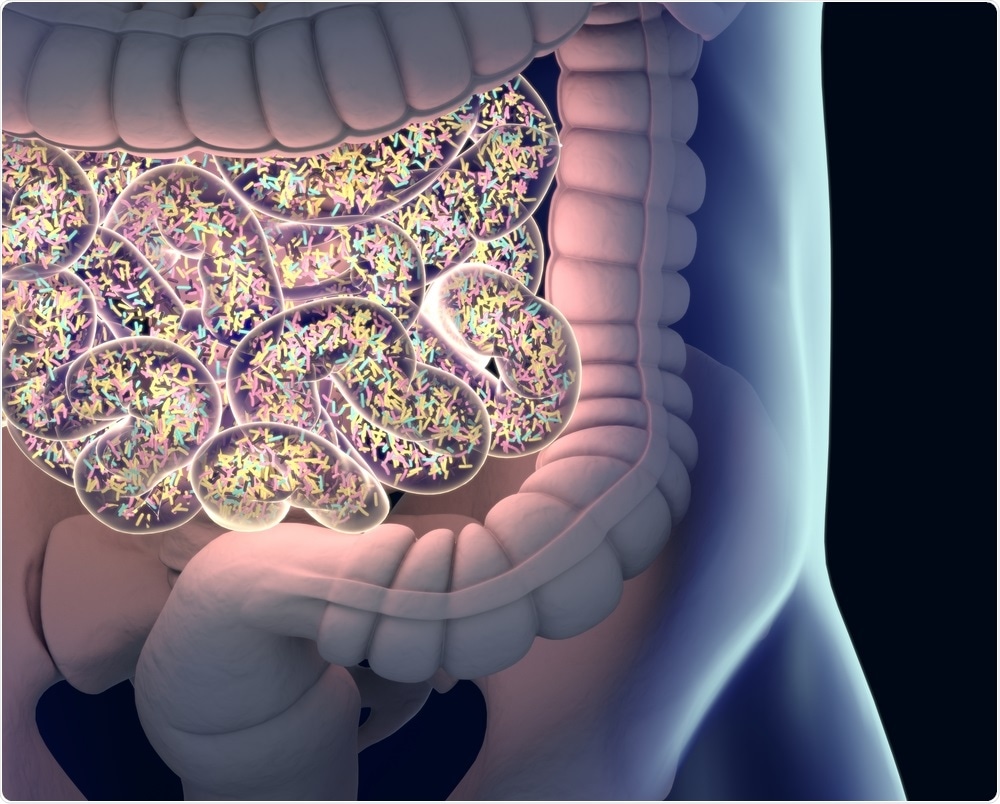

A new study has shed light on how the disruption of commensal bacteria within the gut can affect the immune system and lead to age-related pathologies.

Anatomy Insider | Shutterstock

Anatomy Insider | Shutterstock

Disruption of these bacteria, due to disease or the use of medication, for example, is referred to as “commensal dysbiosis” and is well-known to be associated with various pathologies and even a shortened lifespan.

However, researchers are still unclear about exactly how gut bacteria influence our health and vice versa.

As reported in the journal Immunity, Igor Iatsenko and colleagues from the Bruno Lemaitre lab at EPFL’s Global Health Institute have revealed the mechanism underlying how the immune system causes the commensal dysbiosis that can promote age-related illness.

Using the fruit-fly Drosophila melanogaster, the team switched off the gene that codes for a pattern-recognition receptor protein called peptidoglycan recognition protein SD" (PGRP-SD).

Iatsenko previously showed that this protein detects invading bacterial pathogens and triggers the immune system to target them. Therefore, by turning off the PGRP-SD gene, the researchers created flies with defective immune systems.

The team reports that the knock-out flies had decreased lifespans, compared with healthy flies. The mutated flies also had increased levels of the gut bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, an abundant bacterial species in the gut that produces lactic acid.

Further investigation revealed that the bacteria in the experimental flies produced lactic acid in excess, which then triggered the production of reactive oxygen species - thereby damaging cells and contributing to the aging of tissues.

Here we have a metabolic interplay between the commensal bacteria and the host. Lactic acid, a metabolite produced by the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum is incorporated and processed in the fly intestine, with the side-effect of producing reactive oxygen species that promote epithelial damage."

Professor Bruno Lemaitre, Head of the Laboratory

In contrast, the team found that when they increased PGRP-SD levels, commensal dysbiosis was prevented and the lifespan of the flies increased.

The team suspects that such mechanisms are at play in the mammalian intestine.

There are definitely many more examples like this, and a better understanding of host-microbiota metabolic interactions during aging is needed in order to develop strategies against age-associated pathologies.”

Dr. Igor Iatsenko, Lead Researcher