A new study has found that a childhood stomach bug may be the cause of celiac disease later in life. The findings could pave the way for a vaccine to protect against the disease.

Kateryna Kon | Shutterstock

Kateryna Kon | Shutterstock

Celiac disease is an autoimmune condition in which the small intestine becomes inflamed and is unable to properly absorb nutrients. The disease can present at any age, with the symptoms including abdominal pain and bloating, as well as diarrhea.

Symptoms are brought on by consuming gluten, a common plant-based protein found in bread, pasta, cake, cereals, and beer made from barley. At present, there is no treatment for celiac disease and the only way to manage the condition is to exclude all gluten products from the diet.

The cause of celiac disease is currently unknown. Now, a longitudinal study carried out by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health has suggested that enterovirus may precipitate the condition.

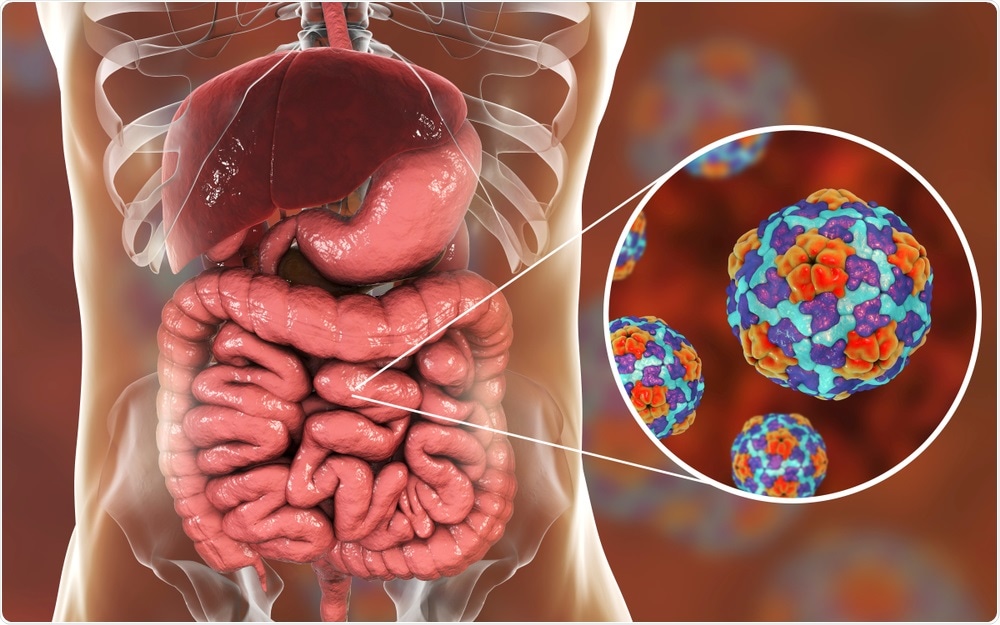

Enteroviruses are a group of viruses that typically cause mild infectious illnesses but can result in serious illness if an enterovirus infects the central nervous system. The two most common enteroviruses are echovirus and coxsackievirus, with some viruses causing polio and hand, foot and mouth disease. Infections are common in children under three years of age, but most adults are immune.

Based on the research, it is now thought that enterovirus causes “impaired barrier function, which in turn increases the risk of celiac disease.”

The study involved taking monthly fecal samples from 220 children between three months of age up to ten years, and testing for the presence of enterovirus and adenovirus. The researchers found that both viruses frequently present before the development of celiac disease antibodies.

Enterovirus was present in 370 of 2135 stool samples, making up 17% of the samples collected. 73 children had at least one positive sample, with viral counts peaking in autumn months.

Adenovirus was confirmed in 258 of 2006 stool samples, making up 13% of samples collected. 61 children had at least one adenovirus-positive sample, but prevalence did not seem to be affected by season, as with enterovirus. This lead to the conclusion that adenovirus was not associated with the development of celiac disease.

Existing research states that celiac disease occurs almost exclusively in people with HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 haplotype, which is seen in approximately 40% of the general population. However, predicting the likelihood of celiac disease developing in groups with these haplotypes isn’t wholly reliable.

Whilst the study authors claim that they avoided the “reverse causation that may bias studies of infections at or after clinical diagnosis of celiac disease”, they admit that they cannot make assumptions about the connection between enterovirus and celiac disease outside of the HLA-DQ2/DQ8 haplogroups. Despite this, they do believe that their findings are “likely to apply to a sizeable proportion of patients with celiac disease.”

Overall, the results of the study suggested that “infections with enterovirus in early life could be one among several key risk factors for development of a disease with lifelong consequences”, and that “several enterovirus types, high titre, and long duration infections in the period after introduction of gluten were involved.”