Adults who lost their vision at an early age have more refined auditory cortex responses to simple sounds than sighted individuals, according to new neuroimaging research published in JNeurosci. The study is among the first to investigate the effects of early blindness on this brain region, which may contribute to superior hearing in the blind.

Loss of visual input from an early age is thought to reorganize how the brain processes sound. This plasticity has been observed in occipital cortex, where parts of the brain that usually respond to vision may take on new roles to handle auditory information. Auditory cortex itself may also become more specialized to support a blind individual’s increased reliance on sound to interact with their environment.

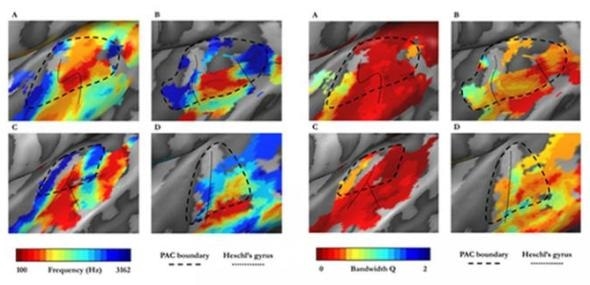

Kelly Chang and colleagues at the University of Washington and the University of Oxford compared auditory cortex response to pure tones in blind and sighted individuals. Although the two groups had similarly-sized auditory cortices, this area was more finely tuned to specific auditory frequencies in people who became blind early in life or whose eyes failed to develop at all. Further research in people who lost — and in some cases recovered — their vision as adults may reveal the mechanisms underlying these changes.