After working on stem cells for several years, scientists have now announced that they have found a way to synthesize structures that look like very primitive human embryos. While some hailed the discovery, others questioned the ethical basis of manufacturing synthetic humans. Though synthetic embryos, or “embryoids”, as they have been dubbed, have been created before, the issue remains valid: how close to a complete embryo is too close, when it comes to simulating human life?

A synthetic embryo is made by manipulating human stem cells in different ways to form embryonic structures. The current method stands out from earlier attempts in its capacity to churn out larger numbers of embryoids.

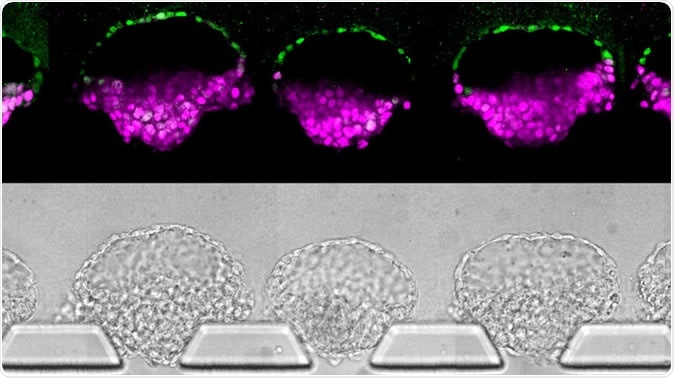

Human embryo-like structures (top) synthesized from human stem cells; they've been stained to illustrate different cell types. Images (bottom) of the "embryoids" in the new device that was invented to make them. Yi Zheng/University of Michigan, Ann Arbor via NPR

Researcher Jianping Fu proudly says, “This new system allows us to achieve a superior efficiency to generate these human embryo-like structures.” He claims that this discovery, “an exciting new milestone”, will help scientists study human development in its earliest stages. According to time-hallowed directives, embryos cannot be used for laboratory research beyond 14 days of development.

This is where Fu hopes his embryoids will come in handy. Not being human in any sense, they do not come under this guideline and will help scientists understand how an embryo actually grows beyond this point. He claims this knowledge will help avert congenital defects and spontaneous abortions. They could also help evaluate the safety of drugs in pregnancy. At present, embryonic research is conducted on residual embryos left unused after in vitro fertilization procedures.

Ethical issues with synthetic embryos

While many embryologists and other researchers in related fields agree that Fu has grasped the Holy Grail of human development in the embryonic stage, others are quick to point out the underlying sensitive questions. For instance, bioethicist Insoo Hyun says, “This team needs to be very careful not to model all aspects of the developing human embryo, so that they can avoid the concern that this embryo model could one day become a baby if you put it in the womb.”

Fu claims that by leaving out placental and yolk sac development, he has ensured that the embryoid is not a full-scale human embryo, but, in his words, “the core of the early human embryo.” The embryoids, however, do produce very early primitive cells, and also develop through what looks like stages of human embryonic development.

Earlier research by Fu centered on human pluripotent stem cells, either from embryo or from adult skin cells engineered to resume their embryonic state. Using chemical signals, these cells, which are of a single type, were induced to develop into other cell types, which is the initial process of embryonic differentiation into different tissues. They went on to develop the “primitive streak”, which is an embryologic structure that establishes the head-tail polarity. However, this was slow and inefficient, with a yield of about 5%.

To increase the gains, the current model no longer uses culture plates. Instead, the technological heart of this innovation is a thin square tray of silicone with four wells placed around a central narrow channel – a microfluidic system. After putting the stem cells into the device, the appropriate chemicals are added to the adjacent wells, and these stimulate the growth of key embryonic structures, leading to the production of an embryoid in a few days. Fu says that hundreds of these structures can be produced using multiple devices, at a 90% success rate. He says, “This is the new standard for controllability, which makes it into an experimental platform.” In this model, the primitive streak starts to show in just four days, and Fu plans to increase the scale of the devices to allow further growth. Moreover, cells were growing and structures like primitive germ cells were developing in a “controlled and synchronized” manner.

These embryoids outgrow their microfluidic homes after only four days, and lack many essential cell types, so that they could not be classified as human conceptuses in any case. With increasing pace of research, however, synthetic embryos that are close to the original natural embryos are sure to arrive sooner rather than later. The burning question for researchers, bioethicists, politicians and funding bodies alike is, will this cross the line that separates human from artificial? The struggle is already on as the NIH worries over whether human embryo models created from human tissue are “organisms” or not.

Even now, mouse embryos have been created and the fight is on to transfer them into surrogate female mice to generate live baby mice. No success has yet been reported. However, if human embryos are created, the technology could backfire if someone, for instance, tried to make modified people. For this reason, Fu, among others, has called upon regulators to disallow the use of such models for anything but scientific research – including reproduction using a synthetic embryo.

Fu comments: “Many scientists are trying to push boundaries, and people are crossing lines. I don’t trust self-regulation.”

Meanwhile, the exponential growth of stem cell research has pushed a guideline review by the International Society for Stem Cell Research. Hyun comments, “If these embryo models end up being complete and are built to have all the components of natural embryos, they should be subject to the same 14-day rule that limits research with natural human embryos.”

The research is published in the Journal Nature.

Sources:

Journal reference:

Controlled modelling of human epiblast and amnion development using stem cells Yi Zheng, Xufeng Xue, Yue Shao, Sicong Wang, Sajedeh Nasr Esfahani, Zida Li, Jonathon M. Muncie, Johnathon N. Lakins, Valerie M. Weaver, Deborah L. Gumucio & Jianping Fu, Nature (2019), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1535-2