Understanding glucagon: The counterpart to insulin

The role of glucagon in diabetes

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1): A key player in diabetes management

The future of glucagon therapy

References

Further reading

Understanding glucagon: The counterpart to insulin

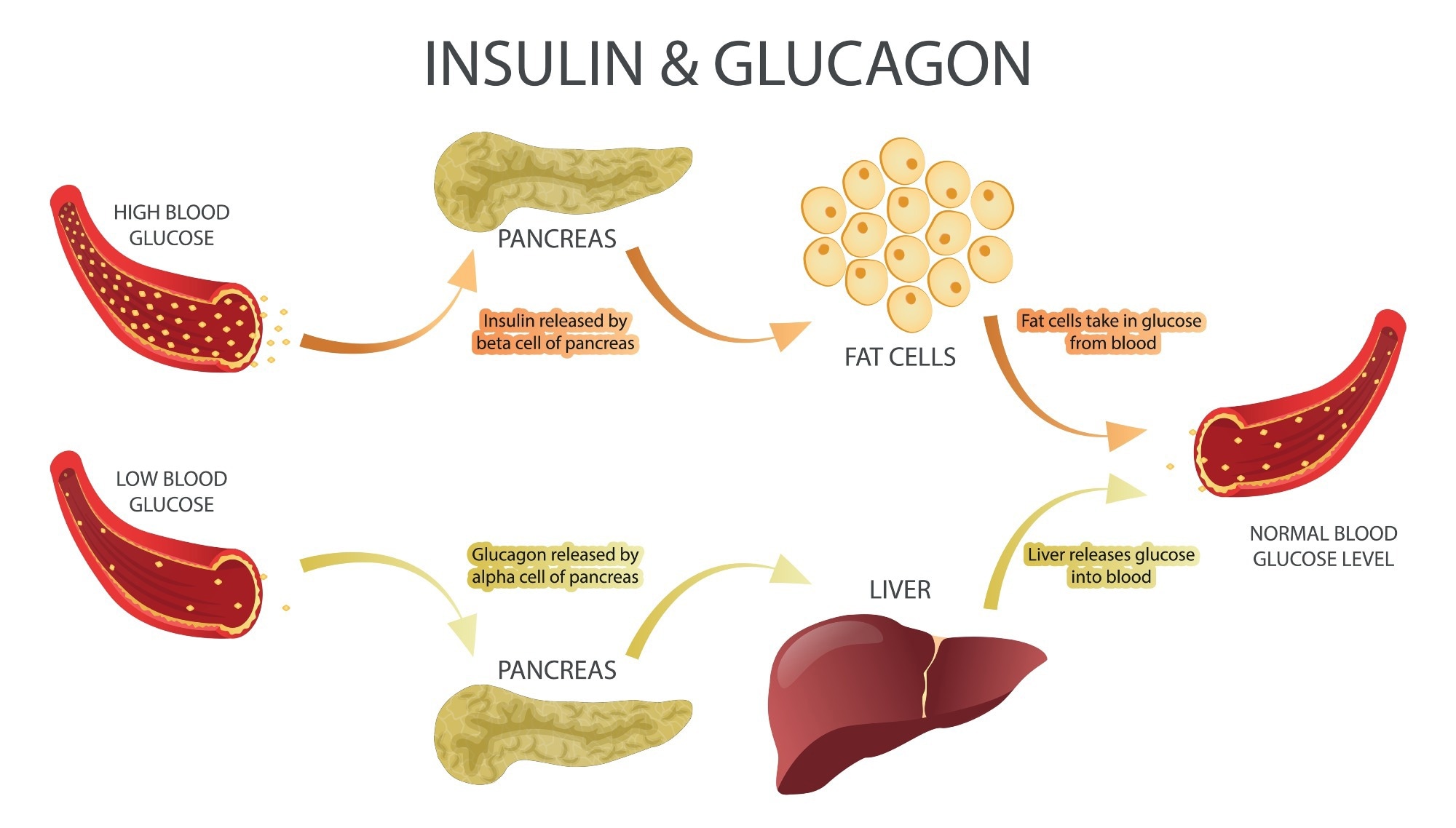

Glucagon is a peptide hormone secreted primarily from the alpha cells of the pancreatic islets of Langerhans. Minor amounts are also produced in the L cells of the intestine and certain neurons of the brainstem and hypothalamus. The basal secretion of glucagon stabilizes blood glucose levels, counterbalancing the basal secretion of insulin.1

Glucagon stimulates the liver to produce more glucose, thus maintaining glucose homeostasis. It balances the action of insulin, which is secreted from the pancreatic islet beta cells in response to hyperglycemia.1,2

In the pancreas, the enzyme prohormone convertase (PC) 2 processes the prohormone proglucagon to glucagon. In the intestine and brain, PC1 converts proglucagon to the incretin hormones, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucagon-like peptide 2 (GLP-2).1,2

Image Credit: DiBtv/Shutterstock.com

Glucagon binds to a G protein-coupled receptor mostly found in the liver but also in the kidney, adrenal gland, gut, and pancreas. The activation of this receptor increases levels of the intracellular signaling molecules, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and inositol triphosphate (IP3). Both cAMP and IP3 eventually trigger the transcription of target genes.1,2

The effect is to stimulate the hepatic breakdown of the complex carbohydrate glycogen to glucose (glycogenolysis), synthesis of glucose (gluconeogenesis), suppression of glycolysis (the anaerobic breakdown of glucose), and inhibition of glycogenesis (the formation of glycogen). This increases blood glucose levels.1,2

When energy is scarce or in high demand, glucagon breaks down lipids and proteins to substrates that can be used to generate energy, simultaneously reducing the appetite and stimulating energy expenditure. It also suppresses lipid synthesis in the liver.1,2

The most potent stimuli for glucagon secretion are hypoglycemia, prolonged fasting, exercise, and after a protein-rich meal. Glucagon levels in the blood may rise 3-4-fold with hypoglycemia or during exercise, and it is a lifesaving homeostatic hormone in severe hypoglycemia.

In prolonged fasting, glucagon primarily stimulates gluconeogenesis. It also ensures adequate glucose supply to the brain and exercising muscle during physical activity..1,2

The role of glucagon in diabetes

Glucagon as a hyperglycemic hormone was first described in 1922 by Kimball and Murlin, who termed it the glucose agonist (later shortened to glucagon). 1,2

Glucagon was initially used to treat insulin-induced hypoglycemia, often encountered in unstable diabetes, because of its ability to induce almost instantaneous rise in blood glucose levels.

Hypoglycemia significantly impairs the health, survival, and quality of life in diabetes mellitus. Yet glucagon remains underused, despite being “the only first-line treatment for severe hypoglycemia that can be administered in a nonmedical environment”.5

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1): A key player in diabetes management

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is associated with hyperglycemia. However, glucagon levels remain high in fasting and postprandial states. Interestingly, this is not suppressed by oral glucose intake but responds readily to intravenous glucose. This suggests the involvement of gut incretins like the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 in diabetic hyperglucagonemia.

GLP-1 and GIP regulate blood sugar after meals by stimulating insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent fashion. They also suppress glucagon release, delay gastric emptying, and suppress appetite centrally, reducing food intake. 6

Aberrant glucagon responses promoting hyperglycemia may be due to the impaired regulation of glucagon and insulin secretion, as well as disrupted alpha cell responses to insulin.1,2

Extrapancreatic glucagon-like peptides may also play a role, opening the way for glucagon receptor antagonist in T2DM therapy.1

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are synthetic GLP-1 analogs that resist natural degradation and thus have a long half-life. They include semaglutide, exenatide, dulaglutide and liraglutide. They lower blood glucose levels without inducing hypoglycemia, and are primarily used to treat T2DM.

Newer GLP-1 RAs have greater homology with human GLP-1. Some require only weekly use by injection, and a few are oral formulations.6

The future of glucagon therapy

Alternative treatments for type 1 diabetes mellitus that have been investigated include whole-pancreas and pancreatic islet transplantation, stem cell transplants, gene transfer or growth factor treatments to help non-islet cells transform into beta cells, and immunization to prevent the formation of beta-cell antibodies.7

Glucagon is a peptide hormone, produced by alpha cells of the pancreas raising concentration of glucose in the bloodstream. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Glucagon is a peptide hormone, produced by alpha cells of the pancreas raising concentration of glucose in the bloodstream. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), G protein-coupled receptor 119 (GPR119) agonists, interleukin-1β Inhibitors, anorectic drugs, sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, engineered zinc-finger protein transcription factors, fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF-21), adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK) activators, and activators of SIRT1 (a member of the sirtuin family of NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases) are other currently available agents.

Bariatric surgery is also capable of producing weight loss and reducing diabetes severity, especially in severe obesity.7

Newer therapies aim to improve beta-cell function, among which are the GLP-1 analogs and GLP-1 RAs. By restoring endogenous insulin response in T2DM, they may stabilize or prevent disease progression. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors are oral agents that increase endogenous GLP-1 levels twofold over the short term.

Moving on from GLP-1 RAs, dual and triple agonist therapy is emerging. These are combinations that target GLP-1 along with GIP or insulin-like growth factors. Tirzapatide (GLP-1 RA with GIPR) is a dual agonist approved in the USA for T2DM therapy in 2022.

Triple agonists target three different receptors, the GLP-1R, the GIPR, and the GCGR, producing complementary but independent impacts on blood glucose and body weight. These are still mostly in the experimental stage. Many such agents are under investigation.6

With their multiple effects on metabolism, GLP-1 RAs are also being investigated for obesity management as well as the treatment of neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, digestive, and musculoskeletal disorders. Some like semaglutide (Wegovy) are now approved for weight loss. 6

References

- Rix, I., Nexoe-Larsen, C., Bergmann, N. C., et al. (2019). Glucagon Physiology. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279127/. Accessed on November 20, 2024.

- Taborsky, G. J. (2010). The Physiology of Glucagon. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/193229681000400607. Available at https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3005043/. Accessed on November 20, 2024.

- Lund, A., Bagger, J. I., Christensen, M., et al. (2014). Glucagon and type 2 diabetes: the return of the alpha cell. Current Diabetes Reports. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-014-0555-4. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25344790/. Accessed on November 20, 2024.

- Kedia, N. (2011). Treatment of severe diabetic hypoglycemia with glucagon: an underutilized therapeutic approach. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome & Obesity. doi: https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S20633. Available at https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3180523/. Accessed on November 20, 2024.

- Zheng, Z., Zong, Y., Ma, Y. (2024). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Nature. Available at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-024-01931-z. Accessed on November 20, 2024.

- Nauck, M. A., Quast, D. R., Wefers, J., et al. (2021). GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes - state-of-the-art. Molecular Metabolism. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101102. Available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33068776/. Accessed on November 20, 2024.

- Aloke, C., Egwu, C. O., Aja, P. M., et al. (2022). Current Advances in the Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines. doi: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9059/10/10/2436. Available at https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10102436. Accessed on November 20, 2024.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 25, 2024