A new paper shows that the cholera germ is an inveterate and rapacious gene stealer, robbing other competing bacteria of up to 150 genes (over 150,000 base pairs) in a single attack. To put this in perspective, the cholera pathogen carries only about 4,000 genes altogether.

The researchers arrived at this conclusion after a painstaking sequencing study to lay out the detailed genome of the Vibrio cholerae, using about 400 different strains of the bacterium, both before and after they had ‘stolen’ genetic material from other bacteria.

The paper titled 'Neighbor predation linked to natural competence fosters the transfer of large genomic regions in Vibrio cholerae' is published in the journal eLife.

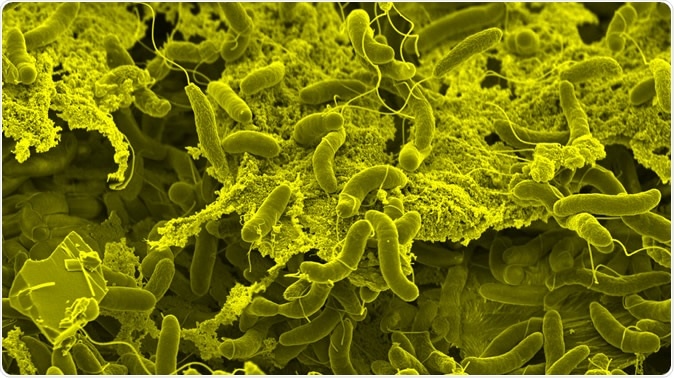

Vibrio cholerae bacteria form dense biofilms on biotic surfaces, which fosters interbacterial killing and horizontal gene transfer. Credit: G. Knott & M. Blokesch, EPFL

Cholera germ: spear wielding predator

A 2015 paper by researcher Melanie Blokesch showed how Vibrio cholerae shoots out a sharp-tipped projectile similar to a spring-loaded spear to puncture any bacteria in the proximity and steal the DNA. The protein that projects the spear is called T6SS, type VI secretion system. This is a molecule-level machine which grabs proteins or DNA from the target cell and transfers them to the predator cell. The T6SS is common to many other bacterial species, and helps them compete with each other.

Digital illustration of cholera bacteria Vibrio cholerae. Image Credit: Creations / Shutterstock

The cholera pathogen is a water-swimming predatory bacterium which snatches new genes from other competing bacteria around it, to incorporate them into its own genome or to exchange some of its material with the new genes, provided both the new and exchanged sequences have sufficient homology. This is called horizontal gene transfer, and is present in all bacteria capable of transformation.

The result is a rapid adaptation of the cholera germ to become more pathogenic and acquire novel characteristics. This phenomenon is responsible for no less than seven major worldwide outbreaks of cholera in the last two hundred years, killing hundreds of thousands of people. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that over 100,000 victims are claimed by cholera each year, from among the 4 million who are affected by this disease that is rampant in low-income countries.

How much DNA can V. cholerae steal at one go?

Earlier studies have attempted to quantify the amount of DNA that a bacterium can possibly absorb into its own genome by culturing bacteria in nutrient media containing heavy quantities of purified DNA. The issue with such studies is the unnatural setting, since in normal conditions long sequences of intact DNA are rarely found. In the case of Vibrio cholerae the T6SS allows long stretches of DNA to be freshly released into the environment to be immediately acquired without degradation by the bacterium. This is in contrast to the DNA released by passive lysis of the cell, and the resulting DNA transfer in the latter case may be correspondingly less. Thus T6SS can facilitate the grabbing of up to 150,000 base pairs in the same stab-and-steal event.

In the case of Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium dwells on shells and other hard biological surfaces containing chitin, and the T6SS mechanism is an adaptation to this. To study this in a more natural environment, the current study looked at non-clonal or unrelated strains of Vibrio cholerae grown together on a chitin-containing medium. This gave them the opportunity to observe how often and how much DNA was exchanged between the two competing strains under reasonably natural conditions.

Implications

The researchers found that strains which had a functional T6SS system which is switched on by chitin achieved DNA transfer much more efficiently compared to other bacteria, and these strains preyed on and killed the other type, taking over large stretches of the preyed-on bacterium’s DNA as well. Thus the cholera germ has a mode of living in its environment that allows it to accumulate significant amounts of intact coding DNA that help it to evolve new characteristics of pathogenicity, forming new strains.

Blokesch says, “This finding is very relevant in the context of bacterial evolution. It suggests that environmental bacteria might share a common gene pool, which could render their genomes highly flexible and the microbes prone to quick adaption.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Neighbor predation linked to natural competence fosters the transfer of large genomic regions in Vibrio cholerae. Noémie Matthey, Sandrine Stutzmann, Candice Stoudmann, Nicolas Guex, Christian Iseli, & Melanie Blokesch. eLife 2019;8:e48212 doi: 10.7554/eLife.48212. https://elifesciences.org/articles/48212