A team of researchers has discovered how one crucial step occurs in the lifecycle of the hepatitis D virus (HDV), which causes the widespread and hard to treat liver inflammation called hepatitis D. The study, which was published recently in the Journal of Virology, could help develop antiviral therapy to control this disease.

Hepatitis D affects 15-20 million people all over the world. It is a defective virus, in that it can only co-infect a cell along with the HBV or superinfect a cell which is already harbouring the hepatitis B virus. This is because the envelope antigens of the HBV are required for the HDV to complete its lifecycle.

However, once this occurs, the resulting infection is more serious in the damage it causes than hepatitis B alone. The World Health Organization statistics say that about 5% or more of people infected with chronic HBV also have HDV infection. This coinfection with HBV and HDV is a very rapidly progressive and severe infection, leading to chronic and sometimes fatal hepatitis with fibrosis and cancer. This is therefore considered the most severe type of chronic viral hepatitis.

The poor prognosis is due to the accelerated and more frequent development of liver cirrhosis or liver cancer when the patient is coinfected with both HBV and HDV.

Though there are therapies available against hepatitis B, these do not seem to have similar efficacy against HDV, resulting in poor rates of cure. Even though the HDV cannot infect cells successfully by itself, it is not wiped out by the HBV treatment based on inhibition of a specific enzyme in this virus. This is because this drug does not completely eliminate the HBV, but only inactivates it. Its presence allows HDV to continue in the liver cell, causing more injury.

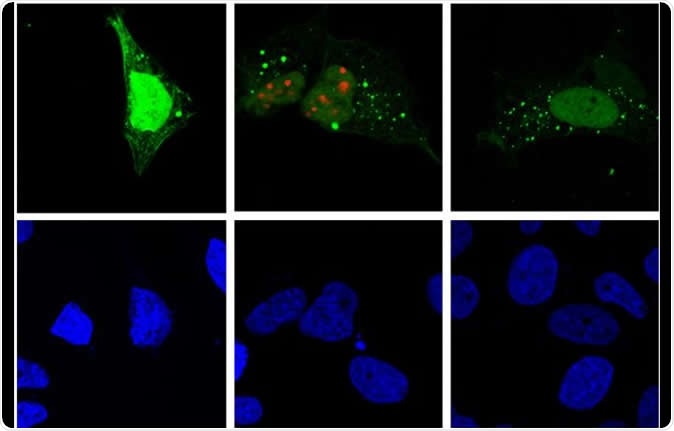

Hepatitis D virus replication (red) induces autophagy (green) in the host cell (fluorescence microscopy). Image Credit: Patrick Labonté, INRS / Shutterstock

Autophagy and replication

The new approach adopted by the current team is to find a therapy directed against both viruses since only this can ensure that HDV will not survive. Exploring the lifecycle of the virus, the researchers found that the HDV was using the same protein as HBV to develop properly, and especially to make copies of itself from the host cell. This protein, called ATG5, is required to clear up debris from inside the cell, in a process called autophagy.

Autophagy is also used to eliminate foreign organisms like viruses, but work-around adaptations have been found in almost every type of virus, including hepatitis C and the influenza virus. This helps them to escape the breakdown caused by autophagy and sometimes, in a clever twist, they make use of autophagy to promote their own metabolism. This is the case with HDV.

The role played by autophagy in the viral lifecycle varies enormously in relation to the process it uses to replicate itself. The researchers therefore looked at whether they could exploit autophagy to help them get rid of the HDV. They focused on determining how autophagy operates in the life cycle of the HDV, the first study of this cellular mechanism in this virus.

They found that the virus changes the way autophagy operates in the cell, in order to promote the replication of the viral genetic material.

How autophagy works in HDV and HBV

Autophagy operates in both viral lifecycles to help them propagate themselves, but at different steps. For instance, it seems to help HBV particles to be secreted from the host cell. In HDV, however, it promotes replication in another way.

With HBV, the viral antigens first induce autophagy but finally prevent the secretion of foreign matter in the form of autophagosomes, the intracellular garbage disposal bags. The HDV protein HDAg also disturbs the flow of autophagy. ATG5 is one of the proteins involved in DNA replication, and is required for HBV to be released from the cell without lowering the amount of HBV genetic material inside the cell.

The current research used CRISPR-Cas9 to show that without this protein, HDV RNA levels within the cell dropped but HDV secretion rates remained unchanged.

Implications

The researchers therefore aim to find a way to inhibit autophagy in a very focused manner, targeting only the HDV, and only for a time, so that other cells can escape inhibition. The close link between HDV and HBV suggests the reason for their sharing the same ATG5 protein to complete the autophagic process.

Using this protein, the researchers could thus block autophagy in both viruses. However, autophagy would also be arrested in all the cells of the host’s body. This could have important and even lethal effects on the wellbeing of the organism.

Researcher Patrick Labonté says, “If we block autophagy, then we are blocking an important function for all cells in the body. We do not know what the long-term effects might be. Autophagy should be inhibited in a targeted and temporary manner.”

While autophagy occurs in the cytoplasm and HIV replication in the nucleus, the first is essential for the second. For these scientists, this raises the question of whether they may be able to find autophagy proteins even inside the nucleus. They are trying to solve this riddle, and hopefully this will further round out the picture of how autophagy helps the HDV to survive and replicate successfully.