Researchers in Italy have demonstrated the potential value of sewage system monitoring for studying trends in the circulation of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) – the agent that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

The authors say the study provides evidence that this type of environmental surveillance could serve as a sensitive tool for the detection and monitoring of ongoing outbreaks, the detection of mild or asymptomatic cases, and the early detection of re-emerging COVID-19.

A pre-print version of the paper is available in medRxiv, while the article undergoes peer review.

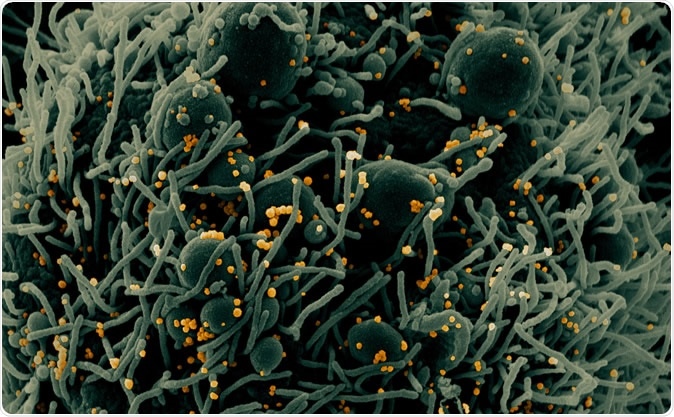

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 - Colorized scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic cell (green) infected with SARS-COV-2 virus particles (orange), isolated from a patient sample. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

About the pandemic

COVID-19 is a public health emergency that was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.

Italy has been one of the world's most affected countries, with the total number of reported cases reaching 205,463 as of April 30.

Asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic carriers of SARS-CoV-2, who mostly go undetected by clinical or lab surveillance, are significant contributors to the infection's spread. They also make it difficult to estimate the degree of circulation in the population and to implement effective transmission control measures.

The potential value of wastewater screening

Regular analysis of wastewaters provides valuable data that can be used to measure viral circulation because the treatment plants receive human excrement from entire communities.

Pathogens present in sewage have been studied by microbiologists for many years, and wastewater screening is well recognized as a tool for public health surveillance or wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE).

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 public outbreak, many studies have reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool samples taken from patients, and some have reported its presence in wastewater systems in the USA, France, and Australia. To date, no such studies of wastewaters have been performed in Italy.

What did the current study involve?

Now, Giuseppina La Rosa (Department of Environment and Health, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome) and colleagues have screened for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in sewage samples taken from wastewater treatment plants in Milan and Rome.

The samples, which were collected between February 3 and April 2, came from two different plants in Milan and one plant in Rome with two pipelines receiving excrement from two different city districts.

Given the absence of a standardized test for detecting SARS-CoV-2 in environmental samples, the team used three different polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays to check for viral RNA.

The first used previously designed broad range primer sets for detection of coronavirinae, while the second used a newly designed primer set that was specific for SARS-CoV-2.

The third was a published nested reverse transcriptase PCR that was specific for the spike protein region (that the virus uses to bind to host cells before releasing its genome).

What did the researchers find?

The team detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in six of the twelve wastewater samples.

The broad-range assay only detected non-specific coronavirus products. In contrast, the published and newly-designed primers that were specific to SARS-CoV-2 generated bands of the size expected for the novel virus.

Importantly, one of the SARS-CoV-2-positive samples collected in Milan during the last week of February was collected only a few days following the first case of an Italian autochthonic positive case being reported, when there was only a limited number of infections in the country.

The researchers say the study shows the potential value of WBE in monitoring virus circulation trends in ongoing outbreaks amongst a given population.

They also point out that screening sewage samples may identify asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases of infection when the number of confirmed and reported cases is low.

"These infected individuals shed viruses into local sewage systems and contribute to virus circulation while remaining substantially undetectable by clinical surveillance, a phenomenon known as the 'surveillance pyramid,'" explains La Rosa and colleagues. "Clinical surveillance, indeed, only captures the tip of the iceberg of viral diseases (hospitalized patients or laboratory diagnosed cases). In contrast, the monitoring of urban wastewaters makes it possible to capture the full extent of the diseases at a community level."

Future directions

Next, the team intends to generate quantitative data on the concentration of the virus in the sewage. Combining information available on the rate of viral shedding and the concentration in wastewaters and treatment plants will enable an approximate estimation of the number of people excreting it.

The researchers also intend to apply the surveillance to water samples available in the Department of Environment and Health of the Italian National Health Institute:

"Such monitoring will provide a picture of the SARS-CoV-2 circulation across the different regions of Italy and, over time, to better understand the virus circulation."

Most important, say La Rosa and team, is that the surveillance of sewage will still proceed once COVID-19 is thought to have passed and circulation is thought to be limited.

"Indeed, sewage surveillance could also serve for the early detection of a possible re-emergence of COVID-19 in urban areas," suggest the researchers.

"Further research will clarify the applicability of WBE to SARS-CoV-2 for prompt detection, the study, and the assessment of viral outbreaks," they conclude.

Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.