The world has experienced many outbreaks of viral diseases. Over the past two decades, we have also seen the emergence of zoonotic human respiratory coronaviruses with pandemic potential. These have been Severe Acute Respiratory Virus (SARS, caused by SARS-CoV-1), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and currently, COVID-19 (caused by SARS-CoV2), which emerged in late 2019. Study of the 2009 H1N1 strain influenza H1N1 pandemic, the most significant respiratory viral outbreak in recent years, can provide insights into the research processes during a pandemic, to prepare for other outbreaks, including COVID-19. Amid these health crises, patients were often treated with drugs such as antivirals repurposed in the hopes of finding a treatment for the infection.

Now, a team of researchers from Royal Melbourne Hospital, Alfred Hospital, and the University of Oxford aimed to investigate how safety and efficacy data for treating the A(H1N1) amassed during the pandemic. They reviewed how many publications existed on clinical trials of treatments and information about where these patients were treated outside of a formal trial setting. The research is available on the preprint server medRxiv*, prior to peer review.

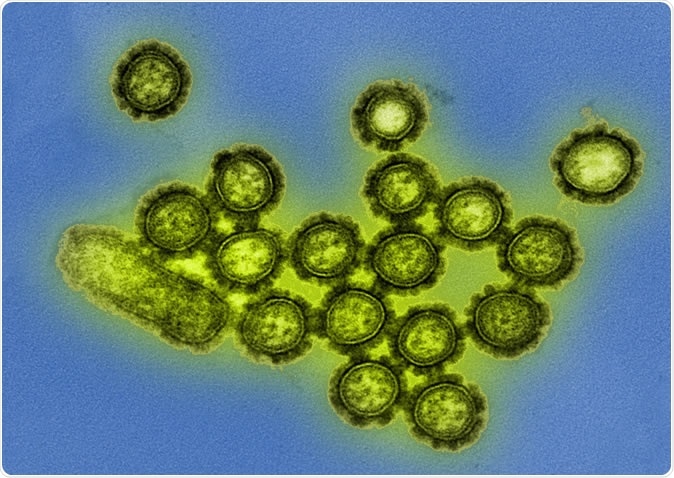

H1N1 Influenza Virus Particles Colorized transmission electron micrograph showing H1N1 influenza virus particles. Surface proteins on the virus particles are shown in black. Credit: NIAID

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

New emerging infections

Viral pandemics constitute a significant threat to global health, triggering outbreaks and pandemics. The potential for future influenza pandemics is possible.

Currently, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is still an active pandemic, infecting more than 4.34 million people.

Novel infections are often hard to treat because there are no approved drugs or therapies for them. As the development of new vaccines can take years, doctors often resort to antiviral medications that are already available.

For instance, many countries have started using antivirals for other diseases such as HIV in treatment patients with COVID-19, including hydroxychloroquine, tocilizumab, and lopinavir/ritonavir. Meanwhile, during the influenza pandemic, doctors used neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) even though safety and efficacy data were lacking.

Safety and efficacy data for treatment

The team wanted to study safety and efficacy data for treating A(H1N1) in 2009. The researchers reviewed the quantity and timing of clinical trial publications of treatments for the disease.

To find these studies, they searched PubMed for all clinical data, including case series, clinical trials, and observational cases, about treatments of patients with influenza. They also gathered information from ClinicalTrials.gov for studies that aimed to enroll patients with the disease.

The study data shows that despite a lack of safety and efficacy data patients who were infected with influenza A(H1N1) were frequently treated with drugs not intended for that viral infection. The results shed light on the use of drugs under compassionate circumstances when doctors resort to other drugs to treat a disease that has no known treatment during an outbreak or a pandemic.

The team found that more than 33,000 treatment courses for hospitalized patients who were infected with the A(H1N1) across 160 publications. Of these, 592 patients received treatment or placebo as participants in a registered clinical trial. The average time when the studies were published was 213 days after the Public Health Emergency of International Concern status had ended.

However, the results of the study highlight the ongoing uncertainty regarding potential benefits and harms of antiviral treatments.

Further, the team emphasized the importance of timely publications of trials to determine the safety and efficacy of the drugs.

“Moreover, we show that the data that was collected on patients was incompletely reported and published after a prolonged delay. We recommend early initiation of multi-center collaborative trials, and pre-approved or sleeper protocols as potential solutions to improve the accumulation of treatment data during a pandemic,” the team recommended.

The researchers conclude, “Our findings demonstrate that we must make improvements to offer patients, and their treating clinicians, evidence-based care during pandemics, including the COVID-19 pandemic. Several drugs are being investigated as a potential treatment for COVID-19, but we note that some early published studies have been poorly controlled,” the researchers wrote in the paper.

“Based on scant scientific data, the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved the emergency use of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19 outside of clinical trials. We must learn from the A(H1N1) pandemic and ensure that trials of therapeutics are performed under conditions that allow for the collection of high-quality, interpretable data to inform future clinical care.”

Currently, many drugs are being used for coronavirus disease, but still, clinical trials are lacking to determine if these drugs are effective and safe to use.

The global pandemic has now spread to 188 countries and territories and has killed more than 297,000 people worldwide.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Source:

Journal references: