However, David Haynor and the team say the difference in mortality rates between countries with the highest and lowest national smoking prevalence seems too large to be mainly accounted for by the effects of smoking. They suspect unidentified confounding factors could still be responsible for any perceived protective effect of smoking.

However, the magnitude of the association observed and the wide-ranging implications this could have highlighted the importance of the further investigation, say the researchers.

A pre-print version of the paper is available in medRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a cell (green) infected with SARS-COV-2 virus particles (purple), isolated from a patient sample. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

The association has been made before

According to Haynor and colleagues, recent studies have shown that smokers are significantly under-represented among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in China, France, Italy, Germany, the UK, the USA, Israel, Iran, South Korea, Kuwait, Mexico, Spain, and Switzerland.

“The apparent substantial under-representation of smokers among COVID-19 inpatients consistently across thirteen countries is remarkable,” says the team. “This is surprising as smoking is generally associated with greatly exacerbating respiratory infections.”

Suggested mechanisms that may confer a protective effect of smoking include altered host cell expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2, the receptor the virus uses to infects cells); the anti-inflammatory activity of nicotine; the antiviral effect of nitric oxide; the effects of smoking on the immune system and vapor heat-related stimulation of immunity in the respiratory tract.

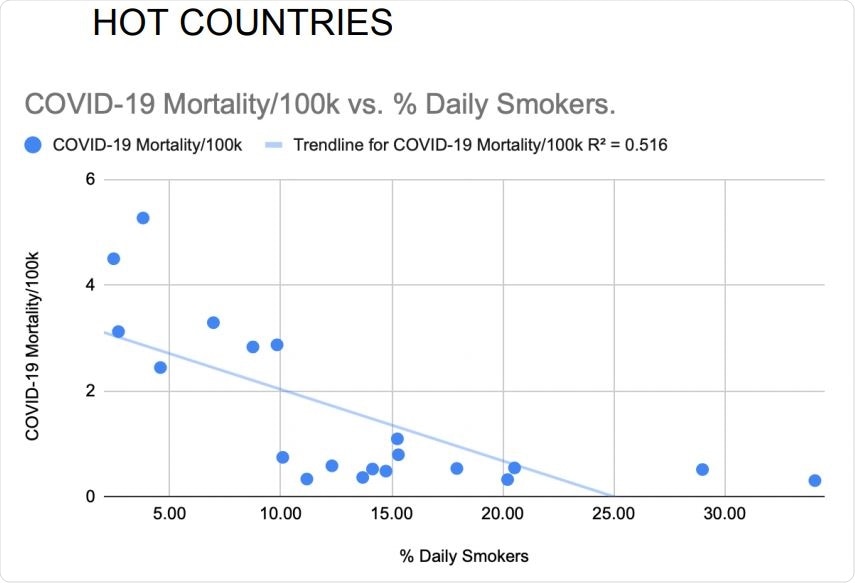

Daily smoking prevalence correlated inversely with national COVID-19 mortality rates of the 20 hottest countries. Pearson’s correlation without adjustments: R=-.718, p=.0002.

It is not clear whether confounding factors are involved

However, the researchers say variations in the studies’ results make it unclear whether confounding factors may have been contributing to the effect. For example, reports generally did not adjust for age and comorbidity and records were not necessarily accurate regarding smoking status.

“We, therefore, sought to test the association in a way that was not subject to any of these confounds,” writes the team.

The researchers also included countries with relatively similar temperatures, given that climate has previously been identified as an important factor in studies of COVID-19. Haynor and colleagues observed that across 19 countries with mortality rates that were 50% higher than among others, all but two fell within a relatively narrow temperature range.

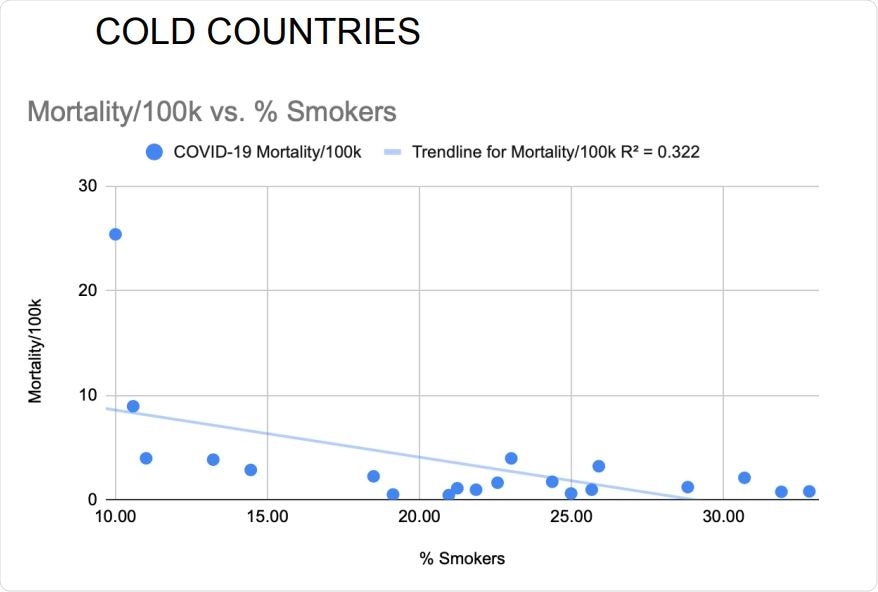

Daily smoking prevalence correlated inversely with national COVID-19 mortality rates of the 20 coldest countries. Pearson’s correlation without adjustments: R=-.567 p=.0046

“We hypothesized that if there was a protective effect of smoking, it might be possible to detect it outside of this moderate temperature band where temperature appeared to be a dominant factor and mortality rates were extreme,” write Haynor and colleagues.

What did the team do?

Using the Johns Hopkins Mortality Analysis database, the team selected 20 “hot” and 20 “cold” countries that had a minimum mortality rate of .03 deaths per 100,000 population.

“A minimum mortality threshold was required because extremely low mortality rates may reflect inadequate testing — furthermore, this limits the impact of floor effects in the analysis,” explains the team.

The researchers examined the relationship between mortality rates and national smoking prevalence after adjustment for known risk factors associated with COVID-19 mortality and after adjustment for independent variables including gender ratio, obesity prevalence, age over 65 years, and average ambient temperature.

The same correlation was identified

A significant inverse correlation between current daily smoking and the COVID-19 mortality rate was identified for hot countries, cold countries, and the two groups of countries combined.

However, after adjusting for multiple confounders, this association remained significant for hot countries and the combined countries, but not for the cold countries.

In hot countries, for each percentage point increase in the smoking rate, mortality decreased by 0.147 per 100,000 population. The mortality rate was several times higher in countries with the lowest smoking prevalence compared with those that had the most significant smoking prevalence.

When hot and cold countries were combined, the mortality rate decreased by 0.257 per 100,000 population.

The difference in mortality rate is “too large” to be accounted for by smoking

The researchers say they think the difference in mortality rate between the countries with the lowest and highest smoking prevalence is too large to be accounted for primarily by the effects of smoking.

“The reason is that even if we assume every smoker is 100% protected from developing COVID-19, there are too few smokers in the population to produce such a large effect, and it is reasonable to assume that there is a confounding influence,” they explain.

The team points out that differences in smoking prevalence may be linked to variations in political structures, economics, or behavioral tendencies that impact the acquisition, testing, diagnosis, treatment, or reporting of COVID-19.

“At this time, there is no clear evidence that smoking is protective against COVID-19, so the established warnings to avoid smoking should be emphasized,” warn Haynor and colleagues.

“However, the magnitude of the apparent inverse association of COVID-19 and smoking and its myriad clinical implications suggest the importance of the further investigation,” they conclude.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.