From the early days of the current COVID-19 pandemic, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been found in the feces of those infected. Cities with a considerable burden of disease have found the virus in wastewater and sewage treatment plants.

-1.jpg)

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Sewage Treatment Eliminates SARS-CoV-2

Earlier research has shown that efficient wastewater treatments do not allow the detection of the virus in the effluent water. A previous study on river water receiving the outflow from a sewage treatment plant in Japan has shown its freedom from contamination by the virus.

Poor Sewage Treatment in Ecuador

However, in most of Latin America, less than a third of wastewater is subject to treatment before flowing out into water bodies and in Ecuador, where the current study comes from, only a fifth is treated. In fact, the capital of this country, Quito, home to about 3 million people, treats a meager 3% of its wastewater before releasing it into surrounding rivers.

Naturally, the rivers carry highly contaminated water along the entire course all the way to the Pacific coast, posing a high health risk to populations living along this stretch and dependent on this water for daily needs, or recreation. The current paper is the first to examine the situation in a country with inadequate sanitary facilities.

Detecting Viral Load in Quito Rivers

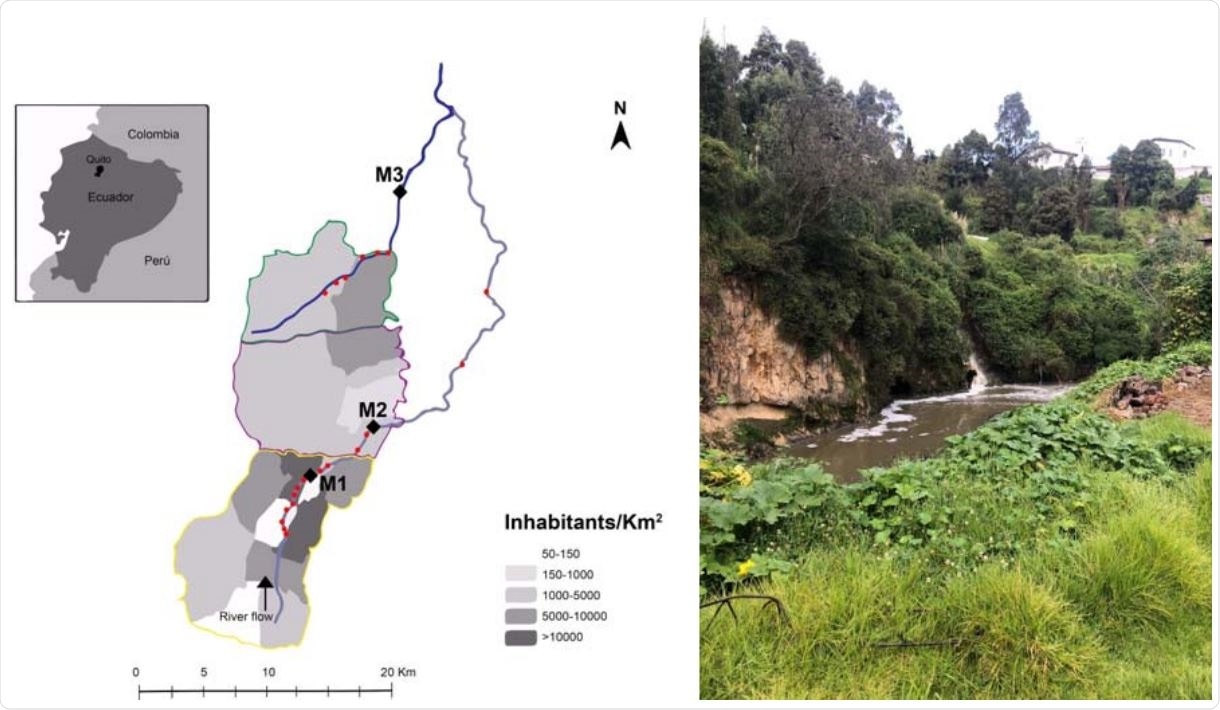

The researchers sampled three river locations in Quito, on June 5, 2020, with two samples each for chemical and biological measurements and two for the detection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The latter analysis consisted of qRT-PCR for human adenovirus, which is an accepted indicator of microbial contamination, and SARS-CoV-2.

The presence of the virus in the river water was related to the caseload for COVID-19 from the Quito sectors that discharge sewage into these points of the river system, for the preceding two weeks up until June 5. The results show that two of three of these sampling points show the impact of human activity on the river system, failing to meet Ecuador’s national standards for aquatic ecology preservation norms.

The human adenoviral load was high, which shows a strong impact on river water. The SARS-CoV-2 genes N1 and N2 were also present in samples from all three locations, with the former showing concentrations of 2.84E to 3.19E GC/L. The latter was present at slightly lower concentrations of 2.07E to 2.23E.

When the researchers correlated this with the cases reported in the feeding sectors, there was a clear link, with positive correlations between the level of contamination and the number of cases. It is noteworthy that the sampling was carried out at the peak of the outbreak in Quito, with the notified cases in the 14 days preceding sample collection coming to a quarter of all COVID-19 cases in the city from the beginning of the current outbreak.

Sampling locations in urban rivers from Quito. Right. Picture of direct discharge of wastewater into Machángara River (sampling point M1).

Contamination and Poor Water Quality

The water quality of the river system sampled here is low, with significant contamination by both organic and inorganic substances. In keeping with generally low ecological values, all environmental parameters, including those of the river water in two samples of the three collected, are above the prescribed standards or the values found at reference sites for the same river basin.

The high human adenovirus levels are only an indicator of significant microbial contamination of the water, as signified in more detail in an earlier study showing that over 26 human microbial pathogenic species were present in river water. This shows the importance of treating sewage before it is released into a riverine system.

Potential Underdiagnosis of Cases

The researchers comment, “Nowadays, in the peak of COVID-19 pandemic in Ecuador, levels of SARS-CoV-2 found in urban rivers of Quito are similar as found in the sewage of Valencia (Spain) with more than 5,000 active cases and Paris in the epidemic peak of cases with more than 10,000 hospitalized cases.”

Another important, but unintended, implication of the study is the significant underdiagnosis of cases, demonstrated by the fact that at the time of sampling, only 750 cases were notified, as against the 5,000-10,000 in Valencia and Spain, respectively, associated with a similar viral load. Also to be noted is the fact that the comparison is made between Quito’s river water, which probably diluted the sewage levels, with sewage itself, in Valencia and Spain.

Implications for Human and Animal Transmission

The study demonstrates the significant potential risk of human infection spreading through river water when untreated sewage is discharged. The difference between this risk and that of microbial detection in many other circumstances is that the detection of viral RNA may not correspond to the presence of viable viral particles in polluted water.

Secondly, the spread of the virus into the environment may have a massive impact on wildlife and agricultural livestock since the coronaviruses are known to spill over to other species with relative ease.

Early Warning System

The third point of practical importance is the potential use of the virus as a surveillance tool to provide early warning of a rise in cases, in situations where diagnostic testing is limited. The sampling of the river water at points along the main locations of sewage discharge could help to detect a rise in infections and thus to control the spread of the virus.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources