Researchers Hugo Zeberg from Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany and Svante Pääbo from Max Planck Institute and Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, Onna-son, Japan, have found that a small fragment of the genetic code that has been inherited by modern humans from Neanderthals could carry the secret of why some people succumb to a severe form of COVID-19 requiring hospitalization, while others recover. Their study titled, “The major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals,” was released online at the preprint review site bioRxiv*.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

The COVID-19 pandemic and severe illness

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has infected over 11.78 million individuals around the world and killed over 542,000 people to date. There seems to be no clear indication as to who would develop a more severe form of the infection and who would not require hospitalization. Some of the risk factors for severe disease that have been speculated include the presence of comorbid conditions such as heart disease, high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and male sex.

Genetic connection

The researchers explained that a study by Ellinhaus and colleagues released earlier this year had shown that there is a genetic association among those hospitalized for COVID-19. A cluster of genes found on chromosome 3 was found to raise the risk of getting respiratory failure when infected with SARS-CoV-2. The team writes that these genetic variants include, “chr3: 45,859,651-45,909,024, hg19”.

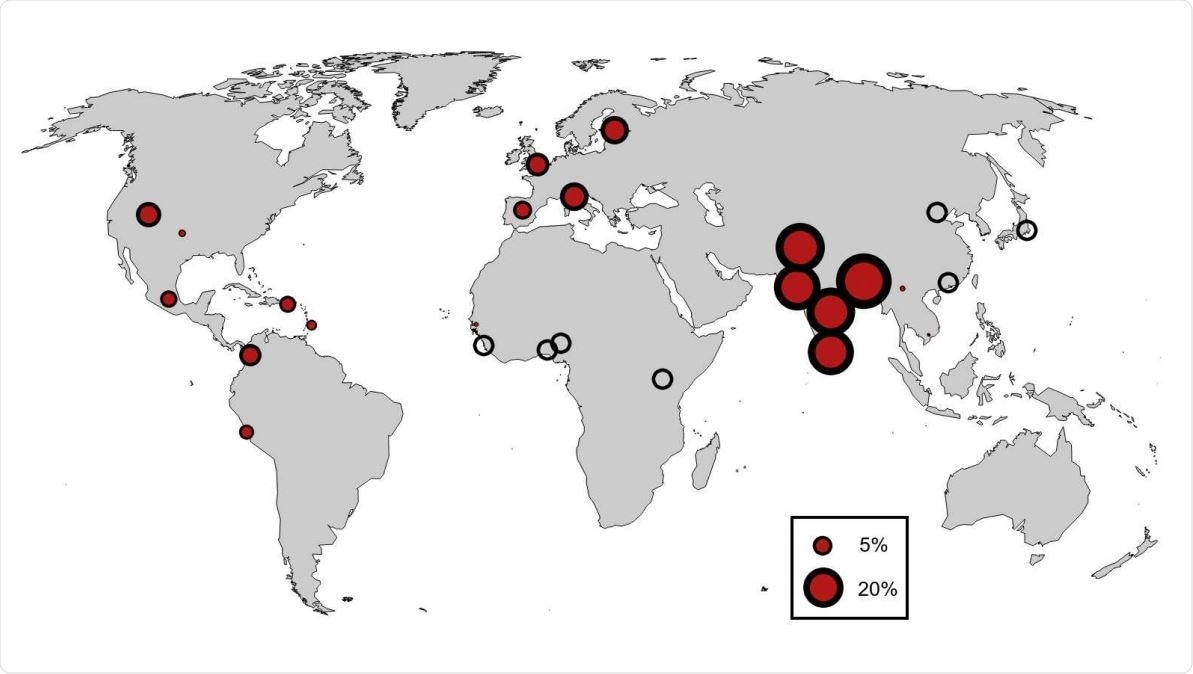

Geographical distribution of the Neandertal core haplotype conferring risk for severe COVID-19. Empty circles denote populations where the Neandertal haplotype is missing. Data from the 1000 Genomes Project.

The Neanderthal connection with the gene sequence

The team of researchers explained that this particular genetic variant found on chromosome 3 has a low rate of recombination or change and has been handed down from our ancestors. They wrote that this genetic variant, or “haplotype,” “entered the human population by gene flow from Neandertals or Denisovans that occurred some 40,000 to 60,000 years ago.” The team explained that Ellinghaus and colleagues in their study had found that the odds ratio of having this haplotype and getting severe SARS-CoV-2 infection was 1.70 – which is significant. This study was conducted to see if this haplotype may have been handed down to modern humans from Neanderthals or Denisovans.

What was done and what was found?

This study was conducted based on data from 3,199 hospitalized COVID-19 patients and control patients. The study was conducted under the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative.

The authors wrote that one of the variants “rs11385942” was present in 33 DNA fragments in one of the genomes of a Neanderthal from Croatia in southern Europe called the “Vindija 33.19 Neandertal”. Four of the genetic variants were found in the Altai and “Chagyrskaya 8 Neandertals” that were found in the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia, which are around 120,000 and 50,000 years old, respectively. None were found in the Denisovan genome. The authors wrote, “Thus, the risk haplotype is similar to the corresponding genomic region in the Neandertal from Croatia and less similar to the Neandertals from Siberia.”

In the next step, the team looked at the risk haplotype, which could be inherited by both Neanderthals as well as modern humans from common ancestors living 500,000 years ago. They noted that possibly the risk gene entered into the modern human genome from Neanderthals.

They concluded that this gene was a significant risk factor for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization. This gene fragment of 49.4 kb size was inherited from the Neanderthals and occurred in around 30 percent of the South Asian population and 8 percent of the European population. In Bangladesh, for example, 63 percent carry at least one copy of this risk factor gene. In East Asia, the gene is present in around 4 percent of individuals, the team wrote. It is absent in African populations, they added.

Expert speak

Joshua Akey, a geneticist at Princeton University, an independent expert, said about this study, “This interbreeding effect that happened 60,000 years ago is still having an impact today.”

Hugo Zeberg, the lead researcher on the study, said that the evolutionary story behind this inheritance is not clear, saying, “That’s the $10,000 question.” He said that this segment could be responsible for a better immune system among those in South Asia and could have been inherited. Another author of the study Svante Paabo added, “One should stress that at this point, this is pure speculation.” Tony Capra, a geneticist at Vanderbilt University who was not part of this study, said that this gene could have been beneficial to the Neanderthals but, “that was 40,000 years ago, and here we are now,” he said.

Genes play a role in the severity of COVID-19, say researchers around the world. Men are more at risk, as are those with certain blood groups. Mark Daly, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School who is a member of the Covid-19 Host Genetics Initiative said that it is still unclear if blood groups play a role in raising the risk of severe COVID-19.

Dr. Zeberg said that the gene fragment needs to be studied in detail adding, “Its evolutionary history may give us some clues.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources