A compelling new study conducted by an international team of researchers has demonstrated that the widely used blood-thinning medication - heparin - can block infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the agent that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Jeffrey Esko (University of California, San Diego) and colleagues showed that as well as requiring the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) for viral binding and entry, SARS-CoV-2 also relies on cellular heparan sulfate.

They also showed that the blood-thinning medication heparin, as well as non-anticoagulant heparin and heparin lyases, all potently blocked the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to human host cells and prevented viral infection.

The spike protein is the viral membrane structure SARS-CoV-2 uses to attach to host cell ACE2 in the initial stage of the infection process.

Now, it appears that heparan sulfate is also required for this spike protein binding, say Esko and team.

“These findings support a model for SARS-CoV-2 infection in which viral attachment and infection involves the formation of a complex between heparan sulfate and ACE2,” say the researchers. “Manipulation of heparan sulfate or inhibition of viral adhesion by exogenous heparin may represent new therapeutic opportunities.”

A pre-print version of the paper is available in the server bioRxiv*, while the paper undergoes peer review.

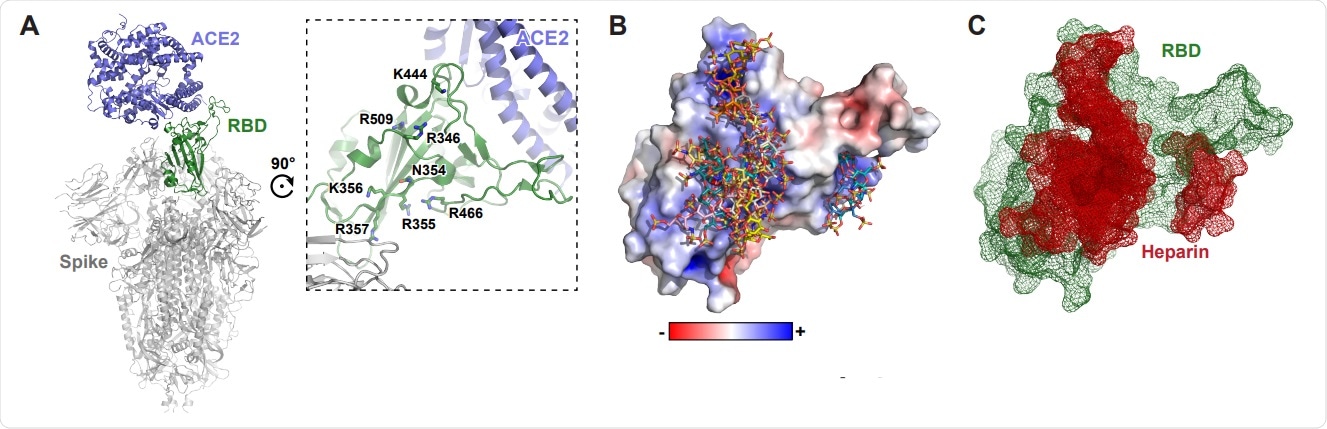

Molecular modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD interaction with heparin. A, A molecular model of SARS CoV-2 S protein trimer (PDB: 6VSB and 6M0J) rendered with Pymol. ACE2 is shown in blue and the RBD in open conformation in green. A set of positivelycharged residues lies distal to the ACE2 binding site. B, Electrostatic surface rendering of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD (PDB: 6M17) docked with dp4 heparin oligosaccharides. Blue and red surfaces indicate electropositive and electronegative surfaces, respectively. Oligosaccharides are represented using standard CPK format. C, Mesh surface rendering of the RBD (green) docked with dp4 heparin oligosaccharides (red).

Exploring alternative approaches to vaccines

Since the COVID-19 outbreak began in Wuhan, China, late last year, the pandemic has now infected more than 13.7 million people and caused more than 588,000 deaths.

Many countries have implemented social distancing and isolation measures to help curb the spread of COVID-19, while researchers around the world race to develop antiviral drugs and vaccines. However, only one antiviral agent - remdesivir - is so far approved for use in COVID-19, and a vaccine may not be available for at least one year.

“Understanding the mechanism for SARS-CoV-2 infection and its tissue tropism could reveal other targets to interfere with the viral infection and spread,” said Esko and colleagues.

The glycocalyx

The glycocalyx or pericellular matrix is an intricate network of glycans and glycoconjugates that all viruses initially come into contact with and must penetrate before they can bind with cell membrane receptors to mediate viral entry.

Many viruses use glycans as attachment factors to facilitate initial host cell binding, including the influenza virus, HIV, and various coronaviruses.

Some viruses interact with heparan sulfate (HS), a highly negatively charged polysaccharide found on some membrane or extracellular matrix proteoglycans.

“HS varies in structure across cell types and tissues, as well as with gender and age. Thus, HS may contribute to the tissue tropism and the susceptibility of different patient populations in addition to levels of expression of ACE2,” suggests the team.

Heparan sulfate was required for SARS-CoV-2 attachment

Now, Esko and colleagues have provided compelling new evidence showing that HS is required for the host cell attachment of SARS-CoV-2.

Docking studies suggested that the spike protein attaches to a heparin/heparan sulfate-binding site through a docking site made up of positively charged amino acid residues in a subdomain of the RBD that lies adjacent to the domain that binds ACE2.

In vitro, the cellular binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein ectodomains required attachment to both HS and ACE2, suggesting that HS acts as a coreceptor, says the team.

Enzymatic removal of HS, genetic studies, and heparin/HS competition studies all showed that whether the spike protein was introduced as a recombinant protein, in a pseudovirus or in native SARS-CoV-2 virions, it attached to host cell HS in a manner that was cooperative with ACE2 binding.

“This data provides crucial insights into the pathogenic mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection and suggests HS-spike protein complexes as a novel therapeutic target to prevent infection,” say the authors.

Treatment with heparin blocked spike binding and SARS-CoV-2 infection

Indeed, the researchers found that therapeutic unfractionated heparin, non-anticoagulant heparin, and heparin lyases (that degrade HS) all potently blocked the binding of spike and prevented infection with both a spike-pseudotyped virus and native SARS-CoV-2.

“This work revealed HS as a novel receptor for SARS-CoV-2 and suggests the possibility of using HS mimetics, HS degrading lyases, and metabolic inhibitors of HS biosynthesis for the development of a therapy to combat COVID-19,” concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources